Report ranks Nevada among worst states for working moms

Megan Hummel knows she’s the exception.

Hummel had 12 weeks of paid maternity leave to take care of her newborn, Alex. But as her time off drew to a close, the 30-year-old had to address the next step: Nevada’s cost of child care.

“I’m a little worried about day care, but we don’t have a choice,” Hummel said in mid-May as she thought about leaving her newborn son to return to her job as an insurance attorney while her husband works as a lawyer. “We both work full time. Sometimes more than full time.”

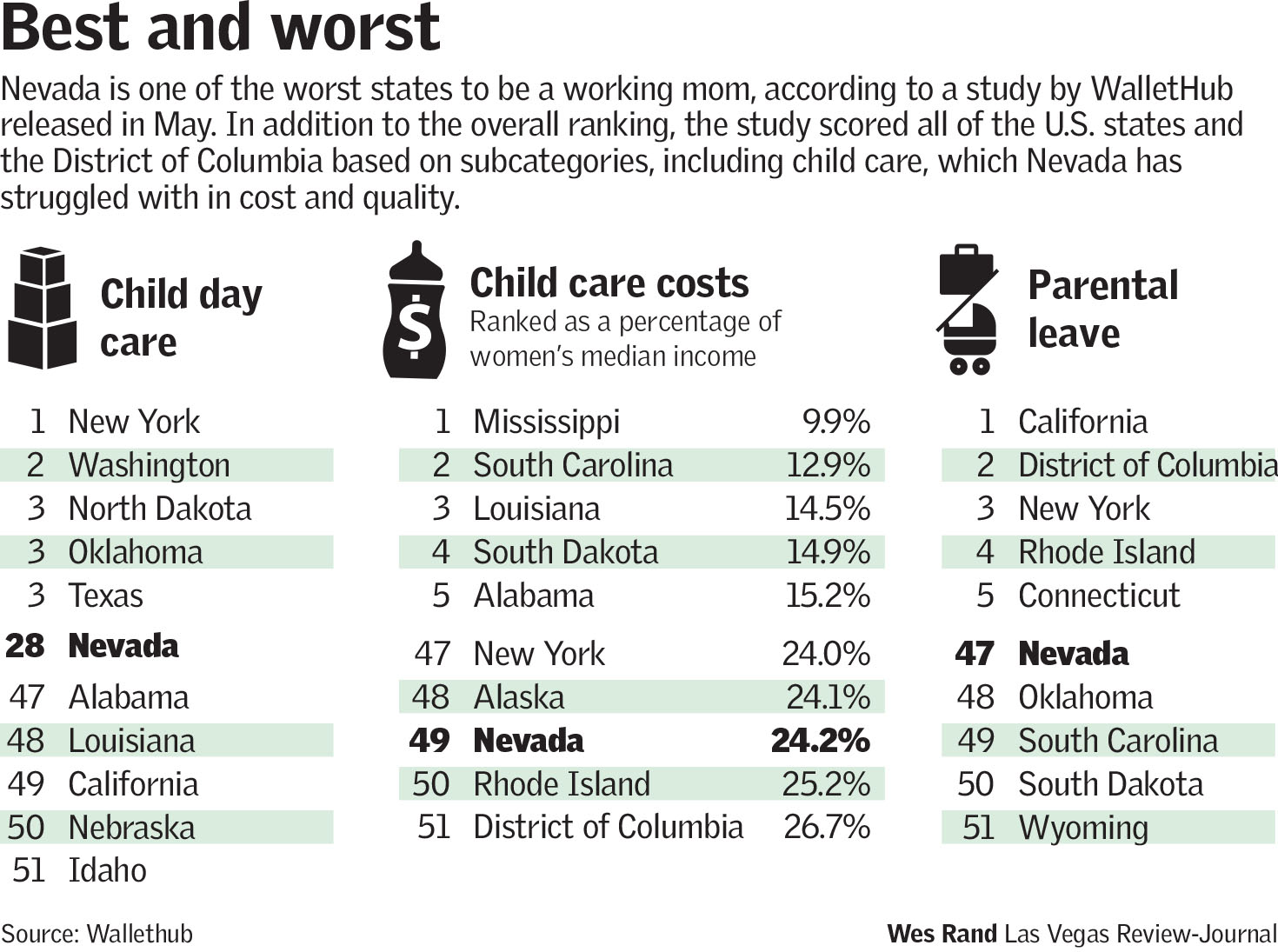

Nevada isn’t very accommodating for working moms such as Hummel, according to a report released in May from WalletHub. The report ranked the state third to last for working moms in the U.S., including the District of Columbia. Nevada came in ahead of only Louisiana and Alabama. The overall score factored in child care costs, parental leave policies and quality of child care.

The results were no surprise for Denise Tanata.

“We’ve been advocating for increased access to higher- quality affordable child care, particularly for working parents, for many years,” said Tanata, executive director of Nevada’s Children’s Advocacy Alliance.

The state’s lack of assistance programs is a major factor in high costs, she said. Although child care subsidy programs exist, Tanata said they cover fewer than 3 percent of eligible families.

She said that a lack of affordable, accessible and high-quality child care leaves mothers trying to “pay for child care and living in poverty, or staying home and having to collect other welfare benefits.”

There are 702 licensed child care facilities in Nevada, according to a representative with the child care licensing division of Nevada’s Department of Health and Human Services. Of those, 462 are in Clark County.

The two states closest in population to Nevada, Kansas and Arkansas, each have at least three times the number of facilities.

Arkansas has 2,297 licensed child care facilities. Kansas, which has about 32,000 more people than Nevada, has 5,505 facilities, according to data from both state’s licensing departments.

Moving forward

Tanata and Sen. Patricia Farley, I-Las Vegas, wanted to pass a bill during the 2017 legislative session to alleviate high-cost, low-quality child care.

The bills would have given tax credits to companies that help employers pay for child care. Farley said it would have shown that Nevada lawmakers saw child care as a priority that helped with workforce development.

“I think because it hasn’t been a priority in our state, we haven’t done much to help foster the facilities coming here and parents having enough money,” she said.

But the tax credits won’t come any time soon. The bill failed after budget committees couldn’t find the funding for it, Farley said.

She said workforce development is a goal of the legislative leadership, but without additional support the people who need it most can’t access workforce development programs. The failed bill would have eased some of the financial burdens on low-income families and single mothers living in poverty, Farley said.

“I realized how pervasive this is in the lower-income earners,” she said. “I think it’s just a vicious cycle, and until we actually break the cycle it’s just going to continue.”

Nevada’s Child Care and Development Program, which subsidizes child care costs for qualifying families, had an average of 5,673 cases in 2015 — 0.19 percent of the state’s population — according to a report from Nevada’s Department of Health and Human Services.

During the 2019 legislative session, Farley will try again to address child care issues.

“Hopefully next session, with all of the education we’ve done this session, we’ll be able to pass the bill,” she said.

The stress of finding quality, affordable child care isn’t new to Farley, who said she’s a single parent with two kids. When her children were young, Farley said she was worried about costs of child care, her children’s education and getting on the mile-long waiting list when she discovered a good facility.

When her 7-year-old daughter entered preschool, Farley worked full time but still tried to be with her daughter as much as possible.

“I was constantly looking for ways to work from home,” she said. “Our options are limited, and it just makes it really hard, especially in a single-parent home.”

Opposing more taxes

Janine Hansen, president of Nevada Families for Freedom, said any answers to Nevada’s child care costs and availability doesn’t lie in changing taxes now or next legislative session.

“There will be other families, other women, that would have an additional tax burden,” said Hansen, regarding the failed bill. “And that tax burden will be created by this (bill).”

She said if the government were to lower taxes in general, families would have more money to afford child care or mothers would be able to stay home with children.

“The child is always better taken care of by someone who loves them then by someone who doesn’t, by institutional care,” said Hansen, a working mother who raised four children.

Personal connections

Tanata said there are economic benefits to providing child care programs and subsidies to working parents.

She said money put into these services will reduce the costs of other social service programs, such as housing, since parents will have to spend less on child care.

But improving Nevada’s situation won’t be easy.

“The truth of the matter is it’s expensive,” she said. “It’s a hard situation.”

Tanata said she and her daughter are testaments to the benefits of child care subsidies.

Tanata had been a single mom for nine years when she went back to college in 1998. She graduated from UNLV’s Boyd Law School in 2003 while receiving help from government programs.

Tanata said she can afford to pay for her 21-year-old daughter’s schooling, something she wouldn’t have been able to do without government assistance nearly two decades ago.

“I think we need to change the focus from these type of programs being entitlement programs,” she said. “It can create a generational change.”

Feeling grateful

Hummel isn’t caught up in legislative bills and political differences over addressing these problems. Her main concerns are her newborn son and making sure he has quality care and education.

There are $200,000 in student loans Hummel has to pay. She has to — and wants to — work while Alex grows up.

“I read somewhere that boys who have working moms grow up to have more respect for women, and I really think it’s going to be important to see both of us work full time,”she said. “That’s how we are able to give him the lifestyle he deserves.”

Alex, a serious baby who rarely laughs, will go to day care and then private school. If Hummel needs to, she can take him to work or visit him during the day because her law firm is flexible for its employees with families.

Hummel said she’s fortunate, even among her friends in professional fields.

“I’m the only one I know of who has paid maternity leave right now,” she said.

She spoke of a friend who felt pressured to return to work within a month of having a baby. Some only had six weeks off. Another friend’s parents moved from China to help with child care.

Even her husband struggled with work during and after Hummel’s difficult pregnancy. He used paid time off to help care for the baby after Hummel went through months of bed rest and lost Alex’s unborn twin before the birth.

His employer gave him two weeks of paid time off, while his wife had almost three months.

Hummel know’s she’s lucky and credits her firm’s flexibility and family focus. She said more businesses should take a supportive approach to employees having and raising children.

“I’ll probably stay at this firm for the rest of my practice if they’ll have me,” she said. “This is the kind of thing that builds loyalty. It’s not just the money.”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240. Follow @k_newberg on Twitter.

Working dads

Nevada isn't good for working fathers either, according to another WalletHub report released June 12. Nevada ranked No. 50 of all states and the District of Columbia. The report looked at slightly different categories than the working mom data, including subcategories for male uninsured rate, deaths because of heart disease and percent of children younger than 18 years old with their father living in poverty.

Rankings for working dads in Nevada include:

No. 51 for child care costs

No. 51 for unemployment rate for dads with children younger than 18 years old

No. 48 for median family income adjusted to the cost of living

No. 48 for males uninsured