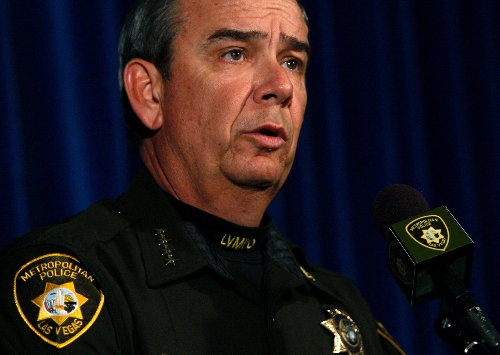

Sheriff announces new use of force policy

Las Vegas police on Monday unveiled a new use of force policy that Sheriff Doug Gillespie said should reduce shootings by his officers and improve the department's relationship with the community.

The new policy, which emphasizes that officers "respect the value of every human life" and advises officers to de-escalate potentially dangerous situations, is part of a six-month review by the agency in the wake of a number of controversial shootings and an investigative series by the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

"At Metro we are committed to saving lives," Gillespie said at a morning news conference. "We will strive to reduce deadly incidents. We will continue to make our jobs safer and to make your community the safest in America."

For a police department, its written policies are the foundation of its actions, and the policy dictating when, and how, officers use force against citizens is arguably the most important. The changes to this policy, which hasn't been overhauled since the 1990s, emphasize smarter interactions with civilians.

New language states the agency is "committed to protecting people, their property and rights" and that "the application of deadly force is a measure to be employed in the most extreme circumstances."

Officers are to be mindful that people not complying with their orders "may not be capable of understanding the gravity of the situation," and those situations should be dealt with without using force, when safe.

The sheriff hopes that reducing the number of shootings will also restore the public's trust. Public criticism of the agency has been high since the high-profile shootings of Trevon Cole and Erik Scott in 2010.

"We realize we need their support, and we have to be transparent as an organization to have the support," Gillespie said. "A police department is only as successful as the positive relationship it has with the entire community."

The agency's officers have five times fired at civilians during the first half of this year, which Gillespie said was the lowest number for a six-month period in 10 years.

CULTURE CHANGE

The new policy brings the Metropolitan Police Department up to some of the "best practices" in policing that the Review-Journal identified last year.

Language emphasizing a respect for human life might seem basic, but a 2002 U.S. Department of Justice report stated that it was a "key factor" in limiting the use of deadly force.

"If the chief stresses conduct that respects the sanctity of human life, and follows up through close administrative review, line officers will respond accordingly," the report states.

The new Las Vegas police policy does not go so as far as those of some agencies; the New York Police Department, which has relatively few shootings, states that deadly force is to be used only as a last resort. Yet even subtler changes in language, combined with other policies and training, have helped other departments reduce shootings.

As Gillespie said, "Culture trumps policy," and to emphasize the new language, the agency this year spent five weeks training all of its 2,700 officers on the changes. They will be required to undergo new reality-based training, where they're required to make decisions on when to use force in real-world scenarios, three or four times per year.

The idea is to get officers to use their language and their heads - instead of the tools on their belt - to resolve situations. At the heart of that is de-escalating - or slowing down or reducing the intensity in situations - a new trend in policing that the Review-Journal also identified.

"Clearly, not every potential violent confrontation can be de-escalated," the new policy states, "but officers do have the ability to impact the direction and the outcome of many situations they handle, based on their decision-making and the tactics they choose to employ."

That could include safely retreating and re-evaluating how to deal with a person wielding a knife, for example. Or it could mean simply waiting for negotiators to deal with an unstable person barricaded alone in his home.

The more patient approach to resolving situations could be a significant cultural shift for what has traditionally been a proud, hard-charging department prone to coming on strong to end situations.

The department, it appears, wants to hold officers responsible for their actions. Also included in the new policy is a requirement that any officer should, when safe, stop a peer from using force that is "clearly beyond that which is objectively reasonable under the circumstances." On top of that, they are required to report their observations to a supervisor.

Lt. James LaRochelle, part of a team that crafted the new policy, said officers will be facing more accountability for using force.

"I think it tells the officer that use of force today will be examined in a much greater light than it ever has before for the agency," he said.

MIXED REACTION

The policy also places new restrictions and guidance on when to use other devices, such as the Taser, beanbag shotgun and pepper spray. From now on, those devices can be used only when the officer is faced with an imminent threat; they can't use them simply to get someone to comply with orders.

When possible, officers are now told that they should give a warning before using such devices and give the person a chance to comply with the warning.

Monday's changes received a mixed reaction from experts and critics.

Samuel Walker, a professor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and author of several books on police accountability, praised the new guidelines.

"I am impressed with the organization, clarity, and detail of this policy," he said in an email. "I am also impressed with the several references to de-escalation. They are clear and forceful and communicate an important message."

But Chris Collins, executive director of the Police Protective Association, which represents the department's rank- and-file officers, said the changes came too quickly.

"Some of these changes were not needed," Collins said. "The sheriff and the department are simply placating the special interest groups."

Allen Lichtenstein, general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, said the policies aren't specific enough. His organization earlier this year had their own recommendations for policy changes, some of which the department didn't adopt.

"It's a step in the right direction," Lichtenstein said. "I don't think it goes far enough."

Among other things, the ACLU of Nevada wanted Las Vegas police to track every time an officer pulls out his firearm, a requirement for officers in Washington, D.C. Las Vegas police only track when an officer pulls out a rifle.

MORE CHANGES COMING

Las Vegas police also are undergoing a review by the Justice Department's office of Community Oriented Policing Services. The results of that study, expected next month, will lead to other changes.

For example, the department hasn't overhauled its Use of Force Review Board, a panel of citizens and officers that rules on whether officers should be disciplined after shootings. The board has been criticized by former members as being a rubber stamp - it has cleared officers more than 97 percent of the time in its 22-year history.

Gillespie, who has also expressed concerns about the board, said Monday that he's waiting on recommendations from the Justice Department on how to change it.

As for the existing changes, the sheriff says they've started to sink in.

"I can tell you within my organization, I hear a lot of talk about slowing these situations down, do I really have to go into that home," Gillespie said. "From a de-escalation standpoint, I believe that message is being sent and is being absorbed."

Contact reporter Lawrence Mower at lmower@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0440. Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281.

Excerpts from new use of force policy

Las Vegas police use of force policy (full report)

Deadly Force: When Las Vegas Police Shoot, and Kill

Las Vegas Review-Journal investigative series