Stolen petroglyph returns to canyon after rocky journey

Leroy Howell scrambles up the rocks of the canyon wall and lays his eyes on what he has come to inspect: a 300-pound boulder bearing the distinct images of several bighorn sheep.

Thoughtlessly -- and illegally -- snatched from its original resting place in the Spring Mountains National Recreation Area sometime in 2008, the petroglyph wound up on display in a remote Pahrump front yard until an alert narcotics detective spotted it the following year while serving a search warrant.

It then sat for the better part of two years in a U.S. Forest Service evidence room in northwest Las Vegas until the thief's case wound through the legal system and federal officials figured out the best way to return it where it belonged.

On this clear July 1 day, after a helicopter has delivered its sacred bounty back to the canyon from which it came, Howell, a member of the Pahrump Paiute Tribe, speaks softly to the petroglyph he has known since childhood: "Back home, huh?"

Then, to no one in particular, he adds, "It looks beautiful. I'm sure it's glad to be back home itself."

RELIGIOUS SYMBOL

While rock art is prized by many for its aesthetic and historical value, tribal members see it as much more. To them, petroglyphs and pictographs are not objects of art.

"They're important religious objects that tell stories," says Richard Arnold, chairman of the Pahrump Paiute Tribe, one of seven Southern Paiute tribes.

At the April sentencing hearing for Michael Cook, the 58-year-old real estate agent and auto mechanic who stole the petroglyph, Howell equated Cook's crime to "taking the Bible and ripping it in half."

Senior U.S. District Judge Edward Reed Jr. acknowledged the serious nature of the offense -- and the need to deter other would-be thieves -- when he sentenced Cook to six months in prison:

"It's a religious symbol of great importance to the tribal members, and that's a factor I think I can fairly take into consideration here, and I will. ... I think it's part of our heritage for all of us. These petroglyphs are something that can never be reproduced, and they're evidence of our past history."

Kelly Turner, district archaeologist for the U.S. Forest Service, says Cook's case is also noteworthy because it yielded Southern Nevada's first felony conviction under the federal Archaeological Resources Protection Act since 2003.

Turner led the effort to return the stolen boulder to its original home and says she never considered any other options.

"It doesn't belong in a museum," she says. "It's kind of like caging a bird."

YARD ORNAMENT

No one knows exactly when this petroglyph's saga began.

"We know it's old," Turner says. "We know it's well over a hundred years old."

It could even be thousands of years old, she adds, but scientists have no accurate way of dating it.

It caught Nye County sheriff's detective Morgan Dillon's eye in June 2009.

Dillon had gone to Cook's residence to serve a search warrant. Investigators correctly suspected they would find a marijuana-growing operation there.

But Dillon also noticed the unusual boulder in the middle of Cook's yard.

"I was thinking that's a pretty nice petroglyph," the detective says. "It was big and pretty intricate, so I had a feeling that it wasn't legal."

Dillon once worked as a seasonal firefighter for the U.S. Forest Service in Northern California and has always enjoyed nature.

"I hate to see people destroying the outdoors," he says.

He also knows that law enforcement officials sometimes get a chance to lock up those who have committed more serious crimes by using backdoor approaches, such as catching them with items taken from protected lands, so he looks out for suspects who may have illegally acquired desert tortoises, cactuses or the like.

The Cook case marks Dillon's first stolen petroglyph, however, and federal investigators are quick to credit him for recognizing the boulder's significance and notifying the Forest Service.

Dillon "had a keen eye and knew what that was," says Thomas Sharkey, who was working as a special agent with the U.S. Forest Service when the boulder was found.

Sharkey, now a special agent for the Bureau of Land Management in Boise, Idaho, went to Cook's property to ask him about the petroglyph.

Cook cooperated, although he initially claimed the boulder was on the property when he bought it.

After investigators disproved that story, Cook admitted he had taken it himself.

Investigators quickly began trying to determine where it had come from.

A 1997 archaeological site record from the Spring Mountains canyon contained a photo of the petroglyph, as well as a photo of another petroglyph depicting three bighorn sheep that remains missing.

Members of the Pahrump Paiute Tribe also recognized the petroglyph Cook had stolen.

"It just absolutely popped out because that piece is so remarkable," Sharkey says.

Investigators seized the boulder after determining it came from Forest Service land.

Sharkey says the BLM, Forest Service and National Park Service frequently get calls about looting, but investigators rarely catch the criminals, and stolen artifacts are rarely returned to their original locations: "When something like that's gone, it's gone."

GUILTY PLEA

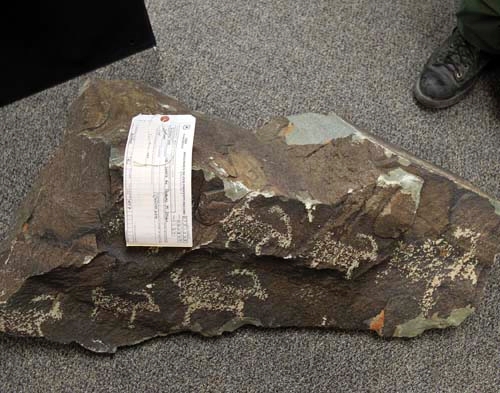

The boulder stolen by Cook has seven bighorn sheep chipped into its front panel. Another sheep on its back side appears older because of the image's darker color, archaeologist Turner says.

Cook claimed he used a rope to pull the free-standing boulder down into his truck.

Turner believes that he first shoved it onto a lower rock art panel, damaging that panel in the process. She also is convinced that he had help.

At least three men have been needed to lift the 300-plus-pound boulder each time it has been moved since it was found on Cook's property. It is approximately 3 feet long, 2 feet wide and 15 inches high.

Turner has no idea why the boulder didn't shatter when it was shoved off the cliff where it was perched. New chips are visible around its edges.

"It's truly amazing there's anything left," she says.

A federal grand jury in Las Vegas indicted Cook in February 2010. He pleaded guilty in October to a felony violation of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act. Felony drug charges are pending against him in Nye County.

At Cook's sentencing hearing, which lasted nearly three hours, he apologized for his actions.

"I realize it was a very stupid move on my part," he told the judge. "I am very much in fear of losing my real estate license and my career."

Assistant Federal Public Defender Rachel Korenblat argued for probation and contended that Cook, who had no prior criminal record, violated the law in the "least harmful way" when he removed the petroglyph and took it home:

"Your honor, he didn't chop it up into several different pieces. He didn't try to sell it. He made a mistake of judgment, your honor, frankly, but he kept it on his lawn, and now the government has that rock back in the same state that Mr. Cook found it in."

She also said he was broke and could not afford to pay restitution. Reed did not require Cook to pay restitution, although prosecutors had argued for $35,000. Reed ordered him to surrender by June 6.

Turner also testified at the hearing, but special agent Sharkey specifically remembers how the courtroom grew silent when Howell and his mother, Clarabelle Jim, addressed the judge.

"They painted a picture that I couldn't do," Sharkey says.

'WRITING OF LITTLE PEOPLE'

Howell says he and his mother had little notice of the hearing but "thought it was important to be there."

Both were born in Pahrump and now live in Las Vegas. At 84 or 85, depending on the source, Jim is a tribal elder and often slips back into her native tongue. The decades have etched creases in her face.

Jim remembers visiting the petroglyphs as a little girl while horseback riding with her father. Known to Southern Paiutes as "grapevine" because of the wild, spring-fed grapes that grow there, the area is considered sacred.

During an interview at her son's home, the petite Jim sits in a chair and recounts how she learned from her mother about the "little people" who live among the rocks of the canyon and made the designs that now decorate many of them.

"It's done by spiritual beings," Howell explains. The Paiute word for petroglyph, "tutugove po-ohp," literally means "the writing of little people."

Howell, 63, doesn't think anybody fully understands the message of the petroglyphs yet.

"I think some of it will be revealed to us later," he says.

Jim was disappointed when she learned the boulder with the bighorn sheep had been removed.

"The animals were human beings before us when the world was new," she says.

Adds Howell: "They were capable of speaking. In other words, they were humanlike."

Both Jim and Howell think Cook deserved a longer prison sentence.

"As far as we're concerned, he just got a slap on the wrist, and that was it," Howell says.

A 2002 case in Las Vegas led to felony convictions for several people involved in looting thousands of artifacts from archaeological sites in Nevada and California.

In December, Las Vegas police arrested a teenager suspected of spray-painting graffiti over prehistoric artwork at the Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, another sacred Paiute site.

Federal authorities later took over prosecution of the case, but the records have been sealed because of the suspect's age.

Archaeologist Turner estimates that hundreds of known petroglyph sites exist in Southern Nevada.

"My crew knows of sites we're never going to tell anybody about," she says. "Sadly, the sites are much more protected if nobody knows where they are."

And she says Native Americans aren't the only ones who equate damaging a petroglyph site to desecrating a church: "There is a spirit to those places. It's why people are drawn to them."

Turner considers Cook a "casual" collector -- "people who love the history of it but don't understand that by going in and digging things up, they're destroying part of the picture."

Those collectors, however, typically snatch items that are easy to pick up, such as arrowheads.

"It takes a lot of work to remove something like a petroglyph," she says.

And, as she would learn, it takes a lot of work to put a petroglyph back where it belongs.

'HELITACK' CREW

For safety reasons, officials decided to return the boulder to the nearby site of the still-missing petroglyph, rather than its original resting place closer to the cliff's edge.

They determined they would need a helicopter to do the job without damaging the boulder or injuring those involved in its return.

With Cook's criminal case closed, a target date of July 1 was set. Turner hoped that would be early enough to avoid both the intense heat of late summer and the approaching fire season that would surely preoccupy the interagency "helitack" crew she wanted for the mission.

Turner attended a briefing with the crew two days earlier at its North Las Vegas Airport base. While the briefing was routine, the subject of the mission clearly was not.

Crew superintendent Cliff White began by announcing, "We're here to move a rock."

They discussed putting the boulder in a cargo net at a nearby landing zone and attaching it to the helicopter with a long line. No one would be allowed underneath the flight path except the helitack crew.

Turner told the crew that the priority for tribal members was the safe completion of the operation.

If necessary, the boulder would be dumped from the air to keep the helicopter from crashing.

RETURN HOME

It's early morning July 1, and the pungent smell of marijuana wafts from the Forest Service's northwest Las Vegas evidence room, where the boulder has been resting for most of the past two years.

Law enforcement officers and members of the helitack crew hoist the rock off the floor and onto a rolling cart that will carry it to the parking lot.

They lift it into the back of a Forest Service truck for its ride to Pahrump.

Word arrives that the helicopter will be leaving North Las Vegas early because a temporary flight restriction, caused by an impending visit from Vice President Joe Biden, soon will go into effect.

During a stop at a convenience store along the way, curious passers-by ask about the petroglyph and snap pictures. Law enforcement officers use it as an educational opportunity, explaining that a man had stolen it and gone to prison.

After meeting at a convenience store in Pahrump, five vehicles take the bumpy, off-road trip to the landing zone. The boulder is moved from the truck's tailgate onto the outspread cargo net, while Jim and her two younger sisters watch quietly.

The rock is wrapped in the net, which is attached to a 100-foot line.

Jim's sister Lorraine, 80, says she is glad the petroglyph is being returned: "Every time I'm sleeping and I wake up, I think about it."

Under a clear blue sky, with temperatures still in the 80s and only a hint of a breeze in the air, the group of about 20 crew members and invited observers waits among the Joshua trees and creosote bushes for the helicopter to arrive.

Cynthia Lynch, 78 and the youngest of Jim's sisters, circles her hands around her eyes like glasses as she tries to make out the approaching helicopter -- a mere speck of reflected sunlight in the distance. Shortly before 11 a.m., it arrives, stirring up dust as it lands.

Pilot Justin Tiesdell Smith, a native of England, works for Sundance Helicopters and says he has delivered plenty of big items from the sky -- air conditioners and glass panels come to mind -- but "not an artifact or anything like that."

Those going to the petroglyph's final destination return to their vehicles and ride along the wash that leads to the canyon.

The wash gives way to a lush green carpet of wild grapevines, their leaves fluttering slightly. Cactuses dot the canyon's rock walls, and flies buzz above animal droppings on the ground.

Wild horses and burros frequent the area but are not there today.

Shortly before noon, the approaching helicopter can be heard. The sound grows louder as it gets closer, its hallowed cargo dangling below.

Five men wearing hard hats have climbed to the designated spot to wait for the petroglyph. In a matter of minutes, the helicopter deposits its load and vanishes.

The men struggle to lift the boulder onto the rock ledge that will be its new home as their feet slide on the slope's loose ground.

With the petroglyph in place, the sheep images once again look out over the canyon, but they can no longer be seen from the wash below.

Leroy Howell, video camera in hand, is the first tribal member up to the spot, which houses many other rock carvings. His cousin Greg Lynch follows, carrying a family photo album that includes a 1992 photo of the petroglyph with the seven sheep.

Cynthia Lynch also makes her way up the canyon wall, smiling as she spots the replaced boulder. She counts each of its sheep, to herself.

A roadrunner emerges and watches the visitors for a while before moving on.

Jim doesn't attempt the climb, and from her shaded seat on a rock at the base of the canyon, she can't see the petroglyph she remembers viewing with her father.

"That's all right," she says with a tone of satisfaction. "As long as its up there, it's OK with me."

Contact reporter Carri Geer Thevenot at cgeer@reviewjournal.com or 702-384-8710.