Daughter’s biography chronicles life, legacy of news photographer father

For four decades, Ted Polumbaum was a freelance photojournalist who traveled the world to create lasting images of news events, newsmakers and routine everyday life for Life, Time, Look and other publications during the heyday of the American general interest news magazine.

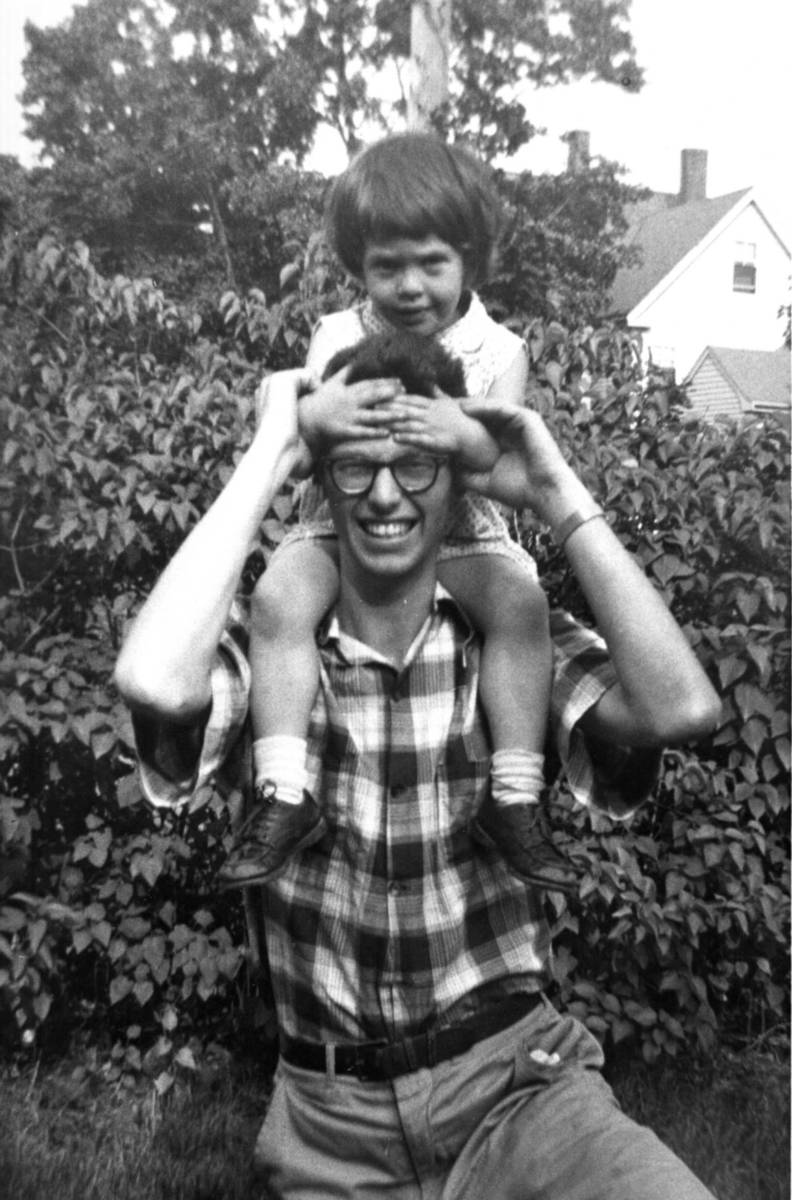

But not even all of that globe-trotting could distract from Polumbaum’s devotion to his family. In a new biography, Polumbaum’s daughter Judy Polumbaum not only chronicles the life and work of the man who was as much a social activist as a journalist, but offers an appreciation of the father who taught her about caring, courage and doing the right thing.

His most important lesson: to have “a real respect for all human beings and an interest in reacting with people at all stages of life,” the Las Vegas resident says. “He got along with everybody and was interested in everybody.”

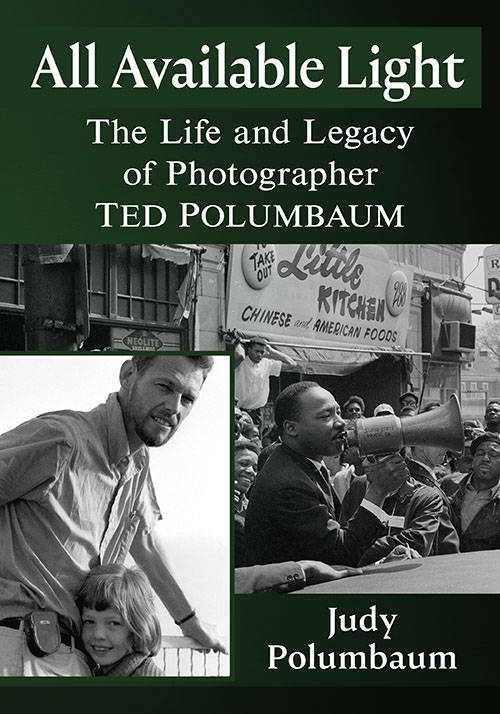

Judy Polumbaum’s book, “All Available Light: The Life and Legacy of Photographer Ted Polumbaum” (McFarland &Company, $45), was released this month.

A useful gift

When Ted Polumbaum was a kid growing up in Mamaroneck, New York, his father, a self-made tobacco company executive, gave him a gift that helped Ted create a future he didn’t yet imagine: a plastic camera. With the help of a commercial photographer at a local drugstore, Ted learned the basics of photography and pursued it as a hobby.

But what Ted really wanted to be was a news reporter. After high school — where he was an editor at his school paper during his junior and senior years — Ted entered Yale University. In the spring of 1943, during his freshman year, Ted was drafted.

He served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and Judy says her father liked to joke that he desegregated the Army long before Harry S. Truman did when he invited two Black servicemen to watch a movie with his unit. After the war, Ted got a newspaper reporting job in Pennsylvania and, later, a job writing TV news copy with United Press in Boston.

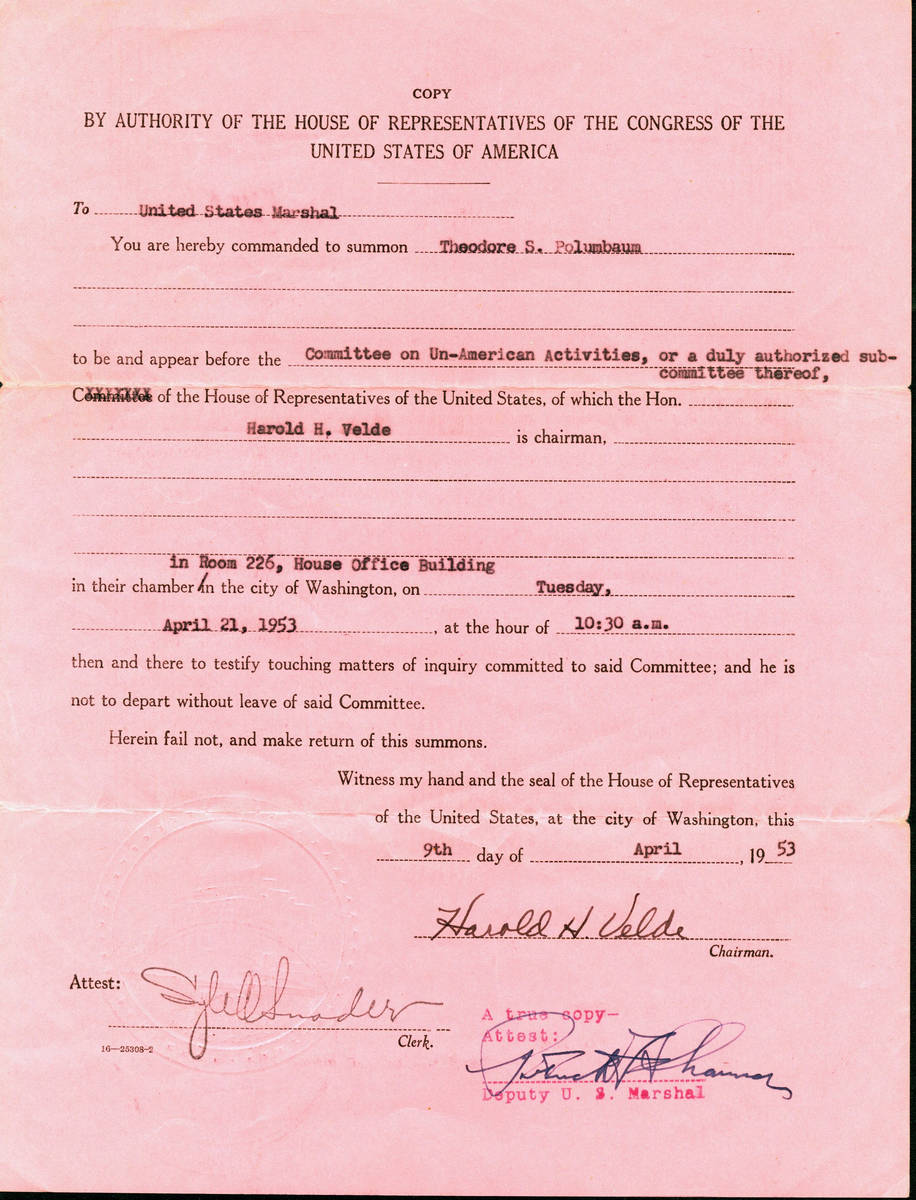

Then, in 1953, Ted was summoned to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which was investigating Communist “subversion in education,” Judy says.

Blacklisted

Polumbaum had been a member of an inconsequential Marxist campus organization in college. But when he testified before the committee, he told members that they had no right to question him about his political beliefs and, Judy writes, accused them of “shredding the Bill of Rights.”

Years later, Judy found a transcript of her father’s testimony.

“I was so impressed he would have the courage to do that,” she says. “He said, ‘It’s not as if people were pulling my fingernails out. Worse things happen to people every day.’ He was so humble. He didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

But the incident prompted United Press to fire Ted, then 28, who by now had a wife, Nyna and a daughter, Miki, at home and another child, Judy, on the way. He was blacklisted and could find no newspaper that would hire him.

“Every time he went for a job interview, the FBI would follow him and show up and tell these people he had this (history) with HUAC and he may be bad news,” Judy says.

A new plan

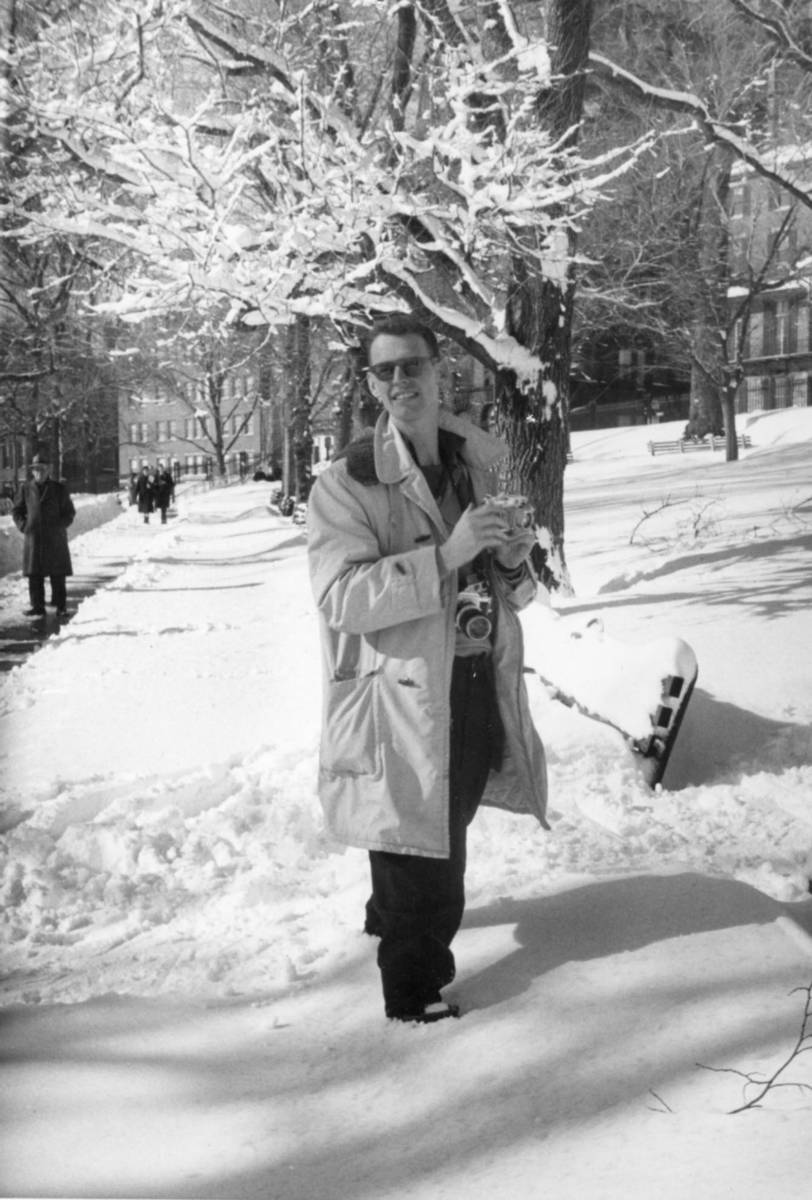

Ted decided to become a freelance news photographer. Over the next few decades, he took assignments for Life, Look, Time, Sports Illustrated, The Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times Sunday magazine and other photo-hungry mass market magazines of the time.

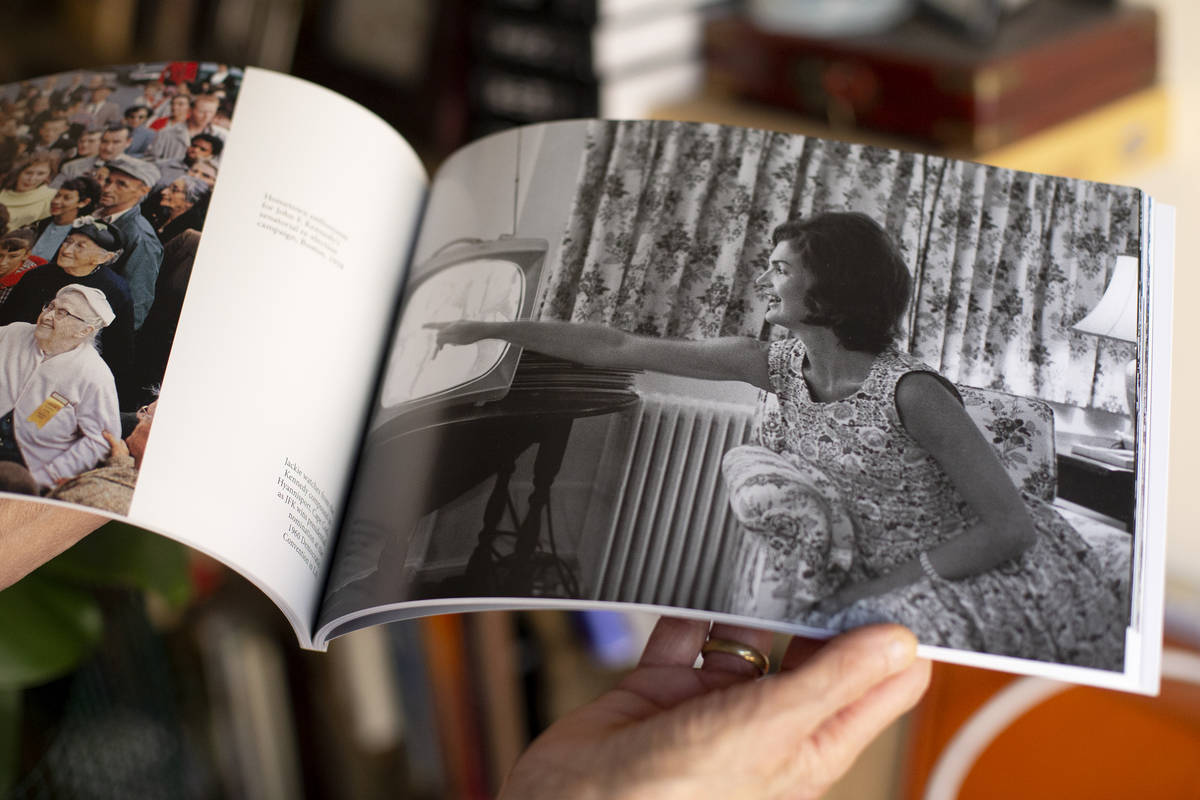

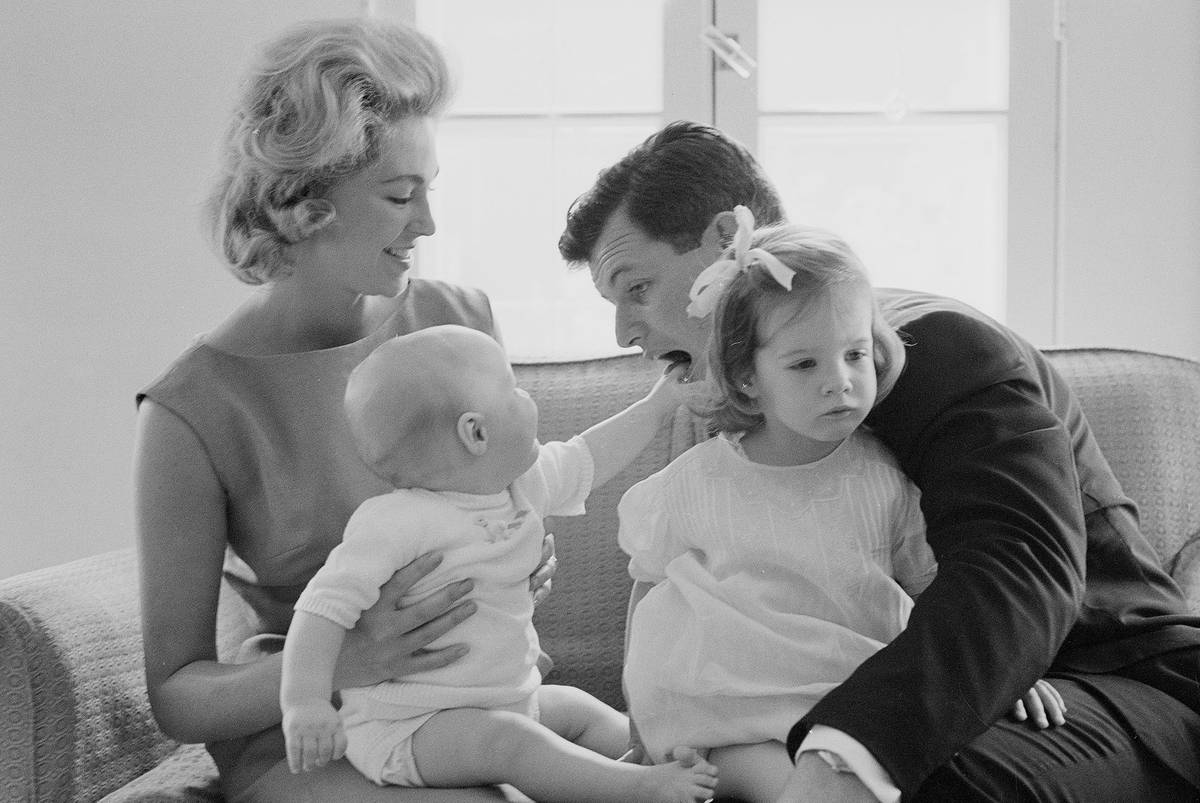

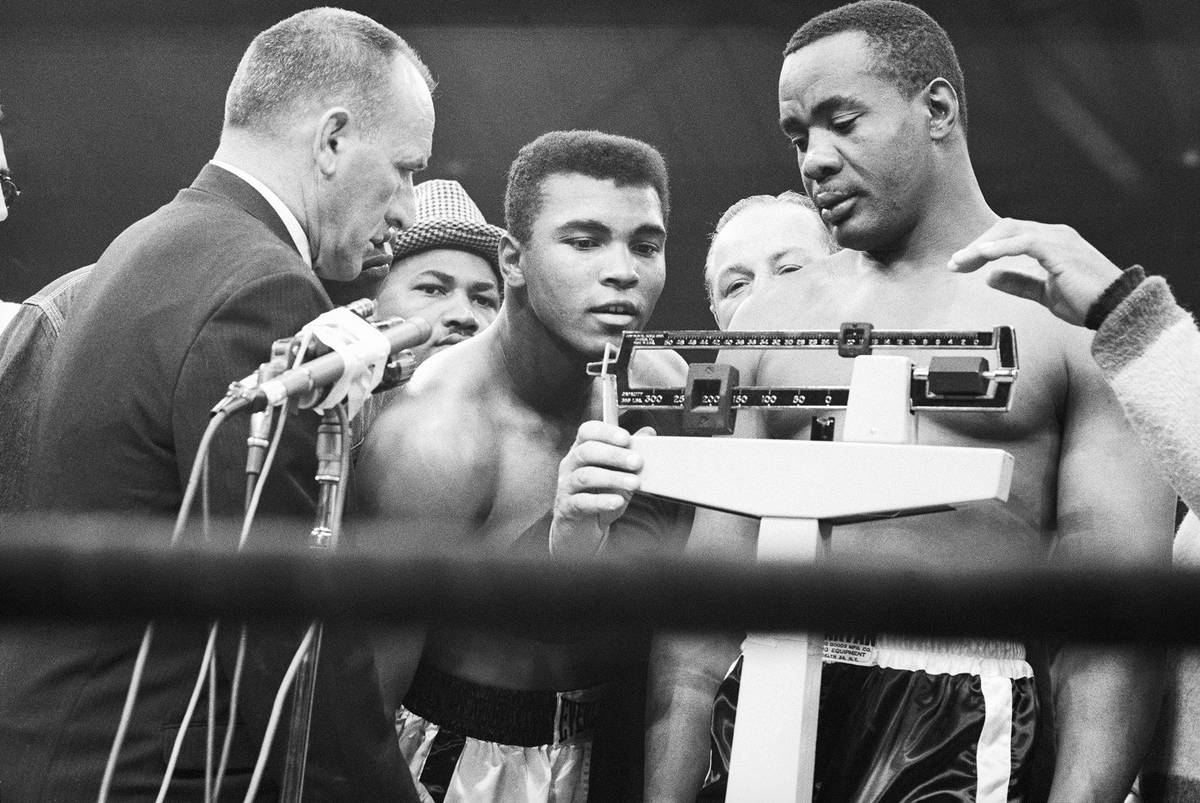

Judy figures her father shot hundreds of assignments for Time-Life and hundreds more for other publications. Living in Boston, he photographed the Kennedys numerous times. He photographed the Boston Marathon and the aftermath of a deadly storm that hit a fishing village in Canada. He photographed Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon, Harry Belafonte and Muhammad Ali, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

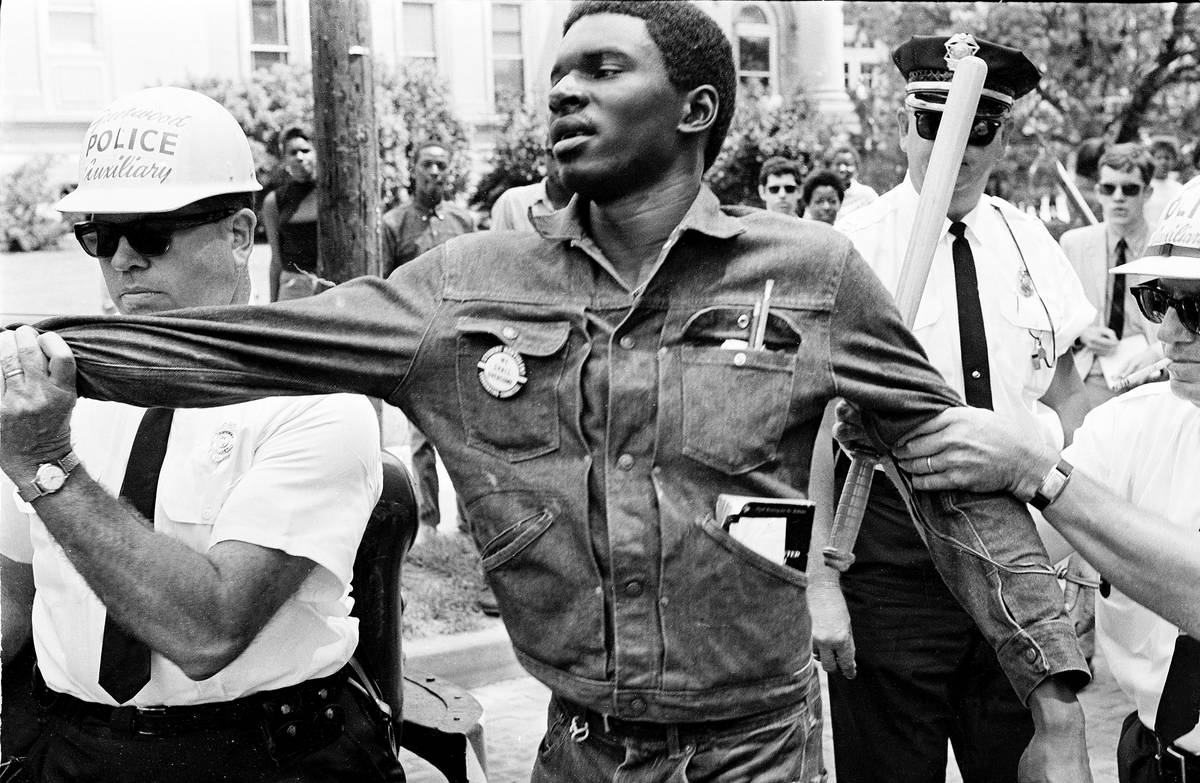

But he had a special affinity for social activist movements, particularly the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War efforts, Judy says. In 1964, he spent a few months in Mississippi — Judy says he later called Mississippi in 1964 “the scariest place he’d ever been” — covering Freedom Summer, in which mostly young, mostly white volunteers went to the state to register Black voters. Closer to home, he covered the racial strife over court-ordered busing in Boston.

Politically, Ted was “a progressive. ‘Liberal’ is too wishy-washy,” Judy says. “He was a social activist. He and my mom worked very hard to turn my small hometown against the Vietnam War.”

Fairness

At the same time, he didn’t violate the mandate for fairness inherent in his job, Judy says.

“Even when he was photographing people whose views he disagreed with, which he often did on assignment — he photographed George Wallace and Louise Day Hicks, who spearheaded the anti-busing movement during desegregation in Boston — he did it straight on. He didn’t want to distort for the sake of politics.”

For Ted, photojournalism wasn’t just a mechanistic recording of events but, Judy says, “a means to try to illustrate what he thought was important in the world.”

And rather than kings and politicians, movie stars or businessmen, “his interest was the ordinary schmoes fighting their daily battles,” she says.

“He wasn’t a photographer of pathos, what people have called poverty porn. He really sought and found the dignity and the humanity even in the most distressed of circumstances.”

Family time

Judy doesn’t recall her father’s travel schedule interrupting family life, and enjoyed the days at a time when he was home. Having a globe-trotting photographer for a father actually was, she says, “pretty cool.”

“My friends loved my parents. Especially my dad. He was a great conversationalist who would talk about the meaning of life and grand philosophical questions with anybody. My brother and I joked that (other kids) purported to be friends but really just wanted to hang out with the old man and shoot the breeze.”

When Life, Look and other magazines began to shut down, Ted transitioned into commercial photography, where in a genre he called “corporate propaganda,” he captured CEOs and factories and images for corporate reports. But he also pursued documentary projects that intrigued him. Judy says one of her father’s final series focused on union workers, and his final exhibition before his death comprised photos about trash collectors at work and home.

Judy credits her mother, Nyna — she and Ted married in 1947, during college — with being Ted’s primary supporter and motivator. After his firing by United Press, Ted got an offer to write catalog copy for a new company called Radio Shack, Judy says. “My mom said, ‘Don’t you dare take that job. You’ll hate it.’ ”

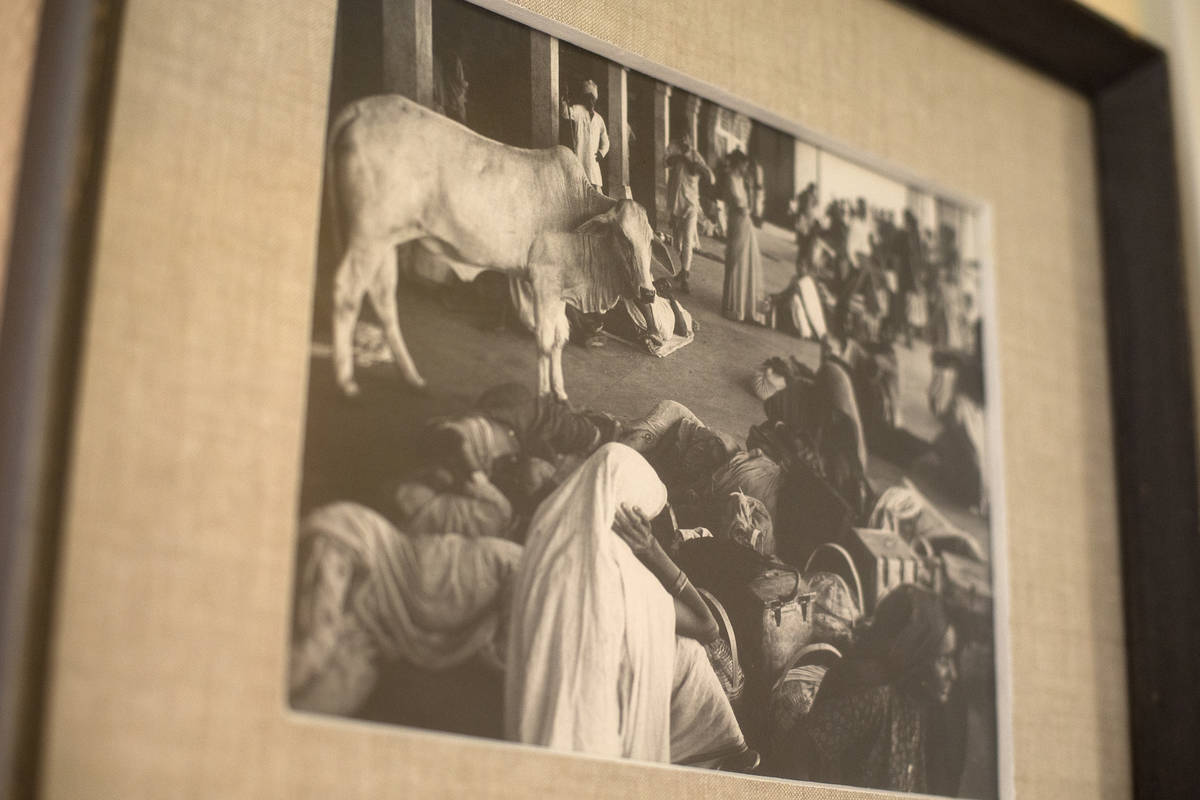

It also was her mother, Judy says, who insisted on using a $9,000 inheritance from Ted’s favorite uncle to buy round-the-world plane tickets for a trip that lasted almost a year and during which the family lived in India for about six months.

And while Ted was inherently progressive politically, “my mother was a total flamethrower who pushed him and emboldened him,” Judy says.

Memories

Ted Polumbaum died in 2001 from what an autopsy determined to be limbic encephalitis. Judy recalls once writing a magazine essay about her father.

“He called it ‘Judy’s fiction,’ ” she says. “I said, Dad, I’m a journalist. I don’t write fiction.’ But he did get to see how much he was appreciated as this wacky, loving, attentive father.”

Judy is a former newspaper reporter and professor emeritus at the University of Iowa and was the first Western scholar to do fieldwork about journalism in post-Mao mainland China. That her father’s isn’t a household name stems, she says, from Ted’s distaste for “celebrity photographer syndrome.”

“He didn’t aspire to be known at all,” she says. “He really was a modest person.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.