Things ‘Jurassic Park’ got wrong about dinosaurs

![]() When “Jurassic Park” came out in 1993, it was the most scientifically accurate depiction of dinosaurs ever put on film.

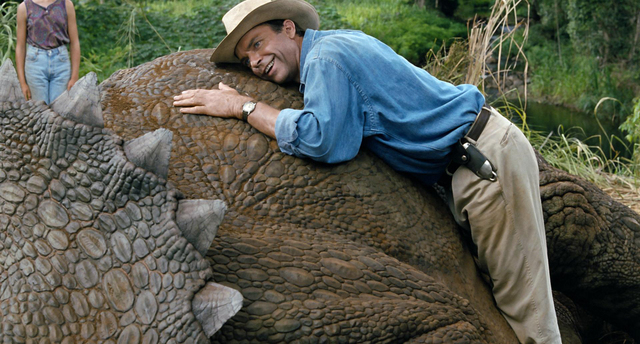

When “Jurassic Park” came out in 1993, it was the most scientifically accurate depiction of dinosaurs ever put on film.

Even though it’s not without its share of goofy pseudo-science (the mechanism for cloning dinosaurs, for instance), it was still a hit with most paleontologists thanks to the way it managed to combine cutting-edge special effects with some of the latest breakthroughs in the field, portraying dinosaurs as living, breathing things and not just B-movie monsters. They were fast, intelligent and dangerous. But most of all, they showed the public what science was learning about dinosaurs at the time.

Since then, a lot of things that were just imaginative speculation within the world of “Jurassic Park” based on then-current theories have been proven true, including the flocking patterns of gallimimus and dinosaurs’ ability to hunt at night.

However, in a lot of other ways, science has progressed beyond director Steven Spielberg’s film, providing a much more detailed view of what prehistoric life was really like.

Here are a few of the things science has learned since Spielberg first opened the gates to “Jurassic Park.”

Feathers

One of the biggest shifts in what scientists know about dinosaurs today versus 1993 — that dinosaurs had feathers — is something that is still struggling to find a foothold in popular perception, partially because of “Jurassic Park.” And not just a little Mohawk of quills or the odd tuft of protofeather, either. As detailed on nature.com, scientists now believe that some dinos were covered from head to toe in flamboyant plumage, bristles, filaments or fuzz, all of which may have helped in a variety of ways — mating rituals, regulating body temperature and even, in some cases, flight.

The first fossil evidence of feathered dinosaurs was discovered three years after “Jurassic Park” hit theaters, in 1996. Since then, paleontologists have made huge strides in understanding what dinosaurs may have looked like. To put it mildly, it’s a far cry from the sleek, leathery, reptilian beasties of Spielberg’s movies. Even Tyrannosaurus rex, says science writer Brian Switek (via io9.com), was “a gargantuan fuzzy carnivore,” while legendary paleontologist Robert Bakker, in a video on Smithsonianmag.com, describes the velociraptor as resembling a “prehistoric, kickboxing killer turkey.”

Dino sizes

Spielberg took some pretty significant liberties with a few of the dinosaurs’ sizes. Velociraptors, for example, are made out to be about twice as big as they really were, resembling instead their relative the deinonychus. In real life, velociraptors were only about the size of a large chicken, standing just 1.6 feet high — in other words, not much of a threat except, perhaps, to small children and pets.

Meanwhile, the frilled, venom-spitting dilophosaurus from the first Jurassic Park movie (which, in real life, was neither frilled nor able to spit venom) is actually significantly undersized. The dilophosaurus was one of the largest predators of the Jurassic period, reaching a length of about 23 feet and weighing in at 1,100 pounds.

One that Spielberg couldn’t have known he was getting wrong, though, was the T. rex. While the height and length in the movie are about right, recent discoveries suggest that the T. rex’s size in terms of mass has been grossly underestimated. According to a 2011 study published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE, using three-dimensional laser scans, an international team of scientists determined that the T. rex was actually about 30 percent more massive — i.e. fatter — than previously estimated.

In order to sustain the extra weight, this meant that the T. rex would have had to eat a lot more, as well.

Intelligence

In the Jurassic Park movies, velociraptors are portrayed as the Hannibal Lecters of the dinosaur world — cunning pack hunters capable of outsmarting even the park’s professional game warden, Robert Muldoon.

While it’s true that velociraptors may have been slightly more intelligent than the average dinosaur, they were not the smartest dinosaurs to have lived, at least, based on their brain size — nor, as Alan Grant (Sam Neill) says in “Jurassic Park 3,” smarter than dolphins or whales or primates. In fact, it’s unlikely that they were even as intelligent as most modern birds.

As for pack hunting — a popular theory when Michael Crichton wrote “Jurassic Park” — the jury is still out on whether any raptors (velociraptors, deinonychus, utahraptors, etc.) ever hunted in packs, despite evidence, according to theguardian.com, that they were social animals at least some of the time.

T. rex speed and senses

Easily one of the most memorable scenes in “Jurassic Park” is the Jeep chase. This portrayal of the Tyrannosaurus as a fast-moving, agile predator capable of keeping pace with a speeding car was about as far as one could get from the slow, lumbering lizards found in earlier Hollywood dinosaur movies.

The question of just how fast a T. rex could run, though — or, in fact, whether it could run at all or just power-walk really, really fast — is one that has been widely debated for years. Some paleontologists have argued for a T. rex with top speeds in excess of 45 miles per hour. However, the general consensus these days, according to i09.com, based on a variety of things including biomechanics and computer simulations, puts the T. rex at a respectable 10 to 25 miles per hour. Unless you’re Usain Bolt, that’s still enough to be terrifying.

As if that weren’t enough to give someone nightmares, science suggests that T. rex was a much more adept and vicious hunter than what even Spielberg’s movies portray. Not only was its eyesight not as bad as “Jurassic Park” makes it out to be (“He can’t see us if we don’t move”), but there’s even some evidence, according to gizmodo.com, that T. rex’s eyesight might have surpassed modern-day hawks and eagles. To top it off, T. rex’s large olfactory bulbs and nerves relative to the size of its brain also indicate that it may have had a sense of smell about on par with a vulture.

Pair those qualities with the most powerful estimated bite force of any terrestrial predator ever at close to 13,000 pounds — for reference, neither a great white shark nor a tiger’s bite force exceed even 700 pounds — and the speed thing probably won’t even matter.

Jeff Peterson is a native of Utah Valley and studied humanities and history at Brigham Young University. Along with the Deseret News, he also contributes to the film discussion website TheMovieScrutineer.com.