Beer, bluster flow freely at Route 91 Harvest fest

It ended where it began: with brews and hearts in hand, the former perpetually verging on empty, the latter always full.

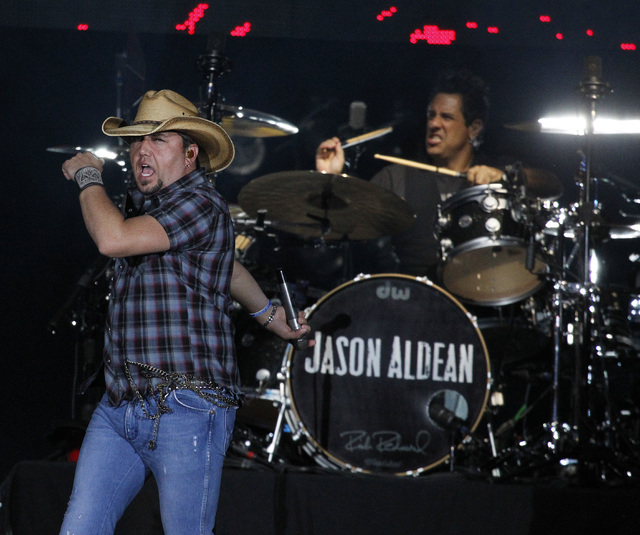

“I’ll find peace / At the bottom of a real tall cold drink, ” Jason Aldean sang Sunday as he closed out the inaugural Route 91 Harvest festival, where the sentiment was as thick as the frothy head of a beer, many of which were guzzled before, during and after 25 hours of country music spread out over three days.

If what Aldean contended was true and solace could indeed be found in the depths of a Budweiser, well, so much good will would have been generated on an asphalt lot across from the Luxor that the world’s warring factions would be laying down their arms right about now.

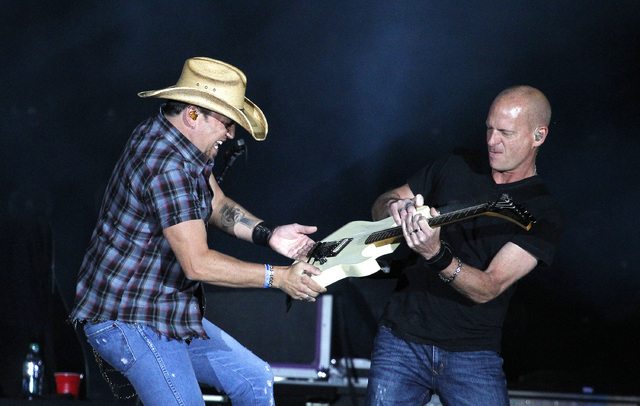

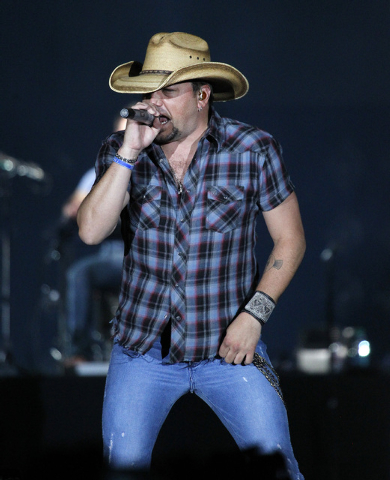

Aldean was a fitting choice to wrap up the festival: He’s a crowd favorite who’s indivisible from said crowd, a star who could pass for a roadie, the kind of flannel-encased ham-and-egger who looks like he should be tuning guitars instead of wielding one to the delight of an audience of 20,000.

But Aldean gets by the same way the blue-collar types in his songs do: through effort and a dogged sense of duty, bulldozing through his repertoire with guitars as outsize as the tires of the jacked-up trucks whose tailgates provide the setting for so many of his tunes.

His voice is like burlap: sturdy, plain and rugged, something that can carry a heavy load, which in Aldean’s case, is the weight of a thousand memories, upon which songs like the wistful “Tattoos on this Town” and the hip-hop influenced “1994” are constructed.

Aldean stood in marked contrast to the other main stage performers on Sunday, especially cowboy Ken Doll Dustin Lynch, an ace balladeer with leading-man looks, and Tyler Farr, a human checklist of country cliches who dry-humped every last genre conceit until his performance bordered on satire — yes, he performed a song titled “Chicks, Trucks and Beer”; no, it was not possible to keep a straight face while he did so.

There was no shortage of masculine aplomb Saturday night either, especially during Dierks Bentley’s winsome set of banjo-fired country rock, where he shotgunned beers with crowd members and led the audience in a boozy sing-along of the weekend’s best song about getting tipsy at an altitude of 20,000 feet (“Drunk on a Plane”).

Bentley was prefaced on stage by one of his influences, Dwight Yoakam, a man who has made explicit the connection between country and rock ’n’ roll for more than three decades now.

Channeling Chuck Berry and Buck Owens in equal measure, Yoakam led his band of rhinestone cowboys in a performance that was like a gene mapping of the genre, excavating its rockabilly roots as he swayed his hips to a country-western swing honed in rock dives as much as honky tonks.

“Time don’t matter to me,” Yoakam sang on bittersweet ballad “A Thousand Miles from Nowhere,” a song where hearts and time become frozen in unison.

Amid this parade of fellas, some feminine perspective was welcomed — and by “perspective,” we mean a shotgun barrel pointed in the direction of any two-timing dudes.

“Behind every woman scorned is a man who made her that way,” Miranda Lambert sang/threatened on “Baggage Claim” as she closed out Saturday’s show.

Lambert’s plucky country pop is posited on self-assertion co-mingled with comeuppance, on affirmations of inner fortitude (“What doesn’t kill you makes you blonder”) mixed with a kind of you’ll-get-yours defiance (“Dirty hands ain’t made for shakin’ / Ain’t a rule that ain’t worth breakin’.”)

Her voice is a like sugar-coated hand grenade: sweet, yet pull the pin — in this case, her highly acute sense of right and wrong — and stand back.

For all her chirpy vengeance delivered with a smile, though, there was a vulnerability beneath it all.

On “Priscilla,” a song directed at Priscilla Presley, she sought advice on how to cope with being the wife of a famous husband, in her case, fellow country star Blake Shelton, who headlined Friday.

“How do you or don’t you get the love you want when everybody wants your man?” she questioned, clad in a Rolling Stones T-shirt, snug black leather shorts and thigh-high boots. “It’s a difficult thing being queen to the king.”

Moments like these, though, were fleeting.

What was lasting was Lambert’s resolve.

“My mama came from a softer generation,” she sang on “Mama’s Broken Heart.” “Where you get a grip and bite your lip just to save a little face.”

Her point: This wasn’t her mother’s generation.

Nor was this her mother’s country.

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow on Twitter @JasonBracelin.

REVIEW

What: Route 91 Harvest festival

When: Saturday and Sunday

Where: MGM Resorts Village

Attendance: 20,000

Grade: B