Herb Hardesty, a tenor sax legend, plays what’s in his heart

The photographs are still and moving at once.

Bruce Springsteen smiles from the mantle.

Willie Nelson’s toothy perma-grin brightens the room.

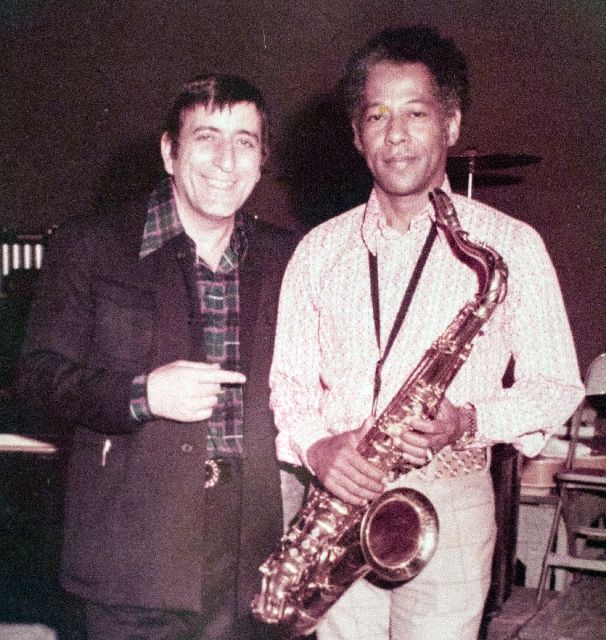

Snapshots of Tony Bennett, Quincy Jones, B.B. King and dozens of other genre-defining musicians form what could pass for an adjunct wing of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Herb Hardesty’s living room.

The well-traveled saxman whom all these luminaries are posed with takes in the photos the way cold bones absorb the warmth of sunlight.

“I’ve got so many pictures, man,” the 87-year-old says, wringing memories from them like he was squeezing water from a sponge.

Hardesty moves into his kitchen, where the walls are filled with more shots, including perhaps the most famous of them all.

In it, Hardesty is onstage, flat on his back, suit jacket off, legs in the air, posed like a hastily drawn letter L.

His sax extends upwards from his mouth, a rocket at takeoff.

He’s soloing upside down.

The standing crowd is packed tight into the club. There doesn’t seem to be any room for movement.

What faces are discernible in the audience are mostly stretched wide in amazement, elastic with awe.

The picture ran in Life magazine in April 1955, shot during Hardesty’s first live dates with R&B legend Fats Domino. Hardesty would tour with Domino for more than 30 years and play on many of his best-known recordings, classics such as “Blue Monday,” “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire,” “My Blue Heaven” and countless more.

Hardesty’s work with Domino is but one facet of a career that has spanned seven decades.

In that time, he’s recorded and performed with Little Richard, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, Bennett and many of the aforementioned greats pictured with Hardesty on the walls of his home on the fringes of downtown Vegas, where he’s lived since 1971.

He’s been on “The Merv Griffin Show,” “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “Late Night with David Letterman,” to name a few, and still continues to tour in Europe three or four times a year.

Hardesty is a titan of the tenor sax, a feisty yet smooth, technically accomplished yet highly instinctive player whose personality saturates his solos.

He can be a complementary or a commanding presence, given the song, but either way, you know it’s him.

“I was told by a good friend of mine, ‘When you play that horn, play what’s in your heart, what’s in your mind, not what somebody else plays,’u2009” Hardesty recalls from his living room couch, his voice as soft as the sofa he’s sitting on.

“You have to be yourself.”

PRESENCE OF GREATNESS

Herb Hardesty’s left foot comes alive first; then his fingers follow suit.

Legs crossed, tapping out the beat with his shoe, he begins playing, letting the notes linger in the air like smoke rings.

Before him, a hundred or so kids sit on the cafeteria floor of Gray Elementary School, rolling their shoulders, clapping along.

“They call it the blues, children,” singer-guitarist Glen Hammond says, pointing to Hardesty, who sits next to him onstage, looking regal in a suit coat and slacks, his hair cloud-white.

Hardesty’s performing in a punchy, funky quintet that pays monthly visits to area schools, exposing kids to live music, sponsored by the New York Jazz and Heritage Foundation.

At first, Hardesty’s playing is smooth and slow simmering, conversational and unhurried, during a show-opening “C Jam Blues.”

He defers to drummer Jimmy Prima, a nephew of the great Louis Prima, on the next tune, bobbing and weaving with the beat, accenting Prima’s fevered playing, as bassist Ernie Cossé shuffles his feet to the rhythm and keyboardist Richard Garcia adds melodic flourishes.

By the time the band gets to Fats Domino’s “My Girl Josephine,” Hardesty’s feelin’ it, letting loose with a solo that combusts like kindling tossed onto a camp fire.

Hardesty gets up out of his seat during the next number, “Blue Monday,” another Domino tune, teasing his solo out to the delight of the crowd.

In the back of the room, a line of kids stand, arms around each other’s shoulders, swaying back and forth.

“You’re in the presence of greatness today,” Hammond beams, looking at the sax man to his left. “He’s a jazz preservationist.”

By the end of the program, a raucous “When The Saints Go Marching In,” even the teachers are dancing.

“Who’s heard of New Orleans?” Hammond asks at the beginning of the performance.

The kids respond by naming some of the city’s signatures: the Saints, alligators, mosquitoes.

An hour later, they’ll add Herb Hardesty to that list.

BIG EASY TO BIG TIME

Herb Hardesty was born in the same city that also sired jazz, and the two are as intertwined as the strands of their shared DNA.

Hardesty’s musical pedigree is indivisible from his native New Orleans — he still owns houses there — where he grew up watching bands march up and down Claiborne Avenue in the 12th Ward from his front porch.

His stepdad was an acquaintance of trumpet great Louis Armstrong, who gave Hardesty one of his trademark instruments when he was a boy.

“That’s when I really got into music,” Hardesty says.

Hardesty recalls his first gig, when he was still in grammar school, performing with a band in a local movie theater.

Someone handed him a drink, which, unbeknownst to Hardesty, turned out to be moonshine.

“Ohhh, man,” he chuckles at the memory. “I thought I was drinking a soft drink or something. And boom! I got up to take a solo and fell back into the screen. The band had to pay for it, so they didn’t get paid that night. They said, ‘See what you did, boy?’u2009”

Back then, Hardesty was getting 35 cents a show, which he considered good money.

When World War II erupted, Hardesty enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was stationed in Jackson, Miss.

He was playing trumpet in the Army band when a commanding officer bemoaned the fact that the group was lacking a saxophonist.

Hardesty, who had never played the instrument before, told his CO that if he got him a sax, he’d learn how to play it.

It took him one week.

Later, Hardesty would be sent to Alabama to join the Tuskegee Airmen, serving in countries such as Germany and Italy as a radio technician. Upon being discharged in 1945, he returned to a career in music, though he didn’t really look at it as a career.

“It never came to my mind,” Hardesty says. “It’s what I felt; what I did. Other people appreciated what I was doing. That was the most important thing.”

Hardesty got his big break four years later, when his friend and fellow musician Dave Bartholomew included him in a studio session with Fats Domino.

“Dave told me, ‘We’re gonna record the Fat Man,’u2009” Hardesty recalls. “And I said, ‘Oh, wonderful, The Fat Man.’ There was a Fat Man on the radio at the time. We were in the studio, and I said, ‘Dave, where’s the Fat Man?’ He said, ‘He’s over there by the piano.’ I said, ‘No, that’s not him.’ I was thinking of the Fat Man who had the radio show.”

Nevertheless, Hardesty would click with Domino, hitting the road with his band in 1955.

Before long, Hardesty would become Domino’s band leader, and even drive the group’s bus from gig to gig.

“I’d be driving at night and everybody’d be sleeping. That’s when I started smoking a lot of cigarettes,” he says, noting that the habit helped him stay awake. “We worked every night, from the East Coast to the West Coast. That’s how much Fats was appreciated.”

Domino performed so much in Vegas, first at the Flamingo, then at the International, which would become the Hilton, that Hardesty decided to move here.

At the Hilton, Hardesty would also play with Duke Ellington, returning to the trumpet.

“Cootie Williams had a toothache. Had to have a tooth pulled,” Hardesty says, explaining how he got the gig after Ellington’s usual trumpet player became indisposed for a time.

After that, Hardesty would hit the road with the Count Basie Orchestra, where he caught the eye of Bennett, who would invite Hardesty to perform with him.

“He had a hundred strings — violins, bass violins,” Hardesty recalls of Bennett’s elaborate show. “He ordered a hundred strings and he got 100 strings.”

Going out on his own

Hardesty walks upstairs and plays a DVD on his bedroom TV.

It’s an old episode of “Austin City Limits,” recorded in December 1978.

The first sound you hear is Hardesty’s trumpet playing, sultry and scalding, its wail equally suggestive of ecstasy and agony.

Tom Waits ambles onto a stage decorated with a pair of vintage gas pumps, taking lazy drags off a cigarette, wearing a halo of smoke like a derelict angel.

The song is “Summertime,” and Waits begins it by telling the story of an old Chevrolet, inhabiting the song the way a method actor does a character.

“He was a kick, man,” Hardesty says of Waits. “People loved him. He’d tell his stories and he’d put his little act on. See how he’s acting?”

Hardesty would play on Waits’ “Blue Valentine” record and tour with him, going to Australia for the first time.

For the most part, though, Hardesty would spend the majority of his time performing with Domino, who would eventually retire.

Hardesty has no intention of following suit anytime soon.

He still makes the rounds overseas to such an extent that his website is also translated into German.

This past October, Hardesty played The Smith Center with blues-jazz great Dr. John, whom Hardesty has known since the ’50s and with whom he performs at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

This year, Hardesty will be playing the fest on his own.

“I’ve always worked it every year, since the beginning, but this is the first time I’m working it under my name,” he says proudly.

At home, Hardesty still plays regularly.

“When I put my horn in the closet, that’s the worst thing to do,” he says. “It should be where I can see it every day. Keeps it in my mind.”

PLAYING TO LIVE

The song’s “Sassy,” and it lives up to its name with Herb Hardesty’s saxophone bawling and protesting like a scorned teenager.

The two-minute rhythm and blues dervish opens “The Domino Effect,” a 20-song collection of Hardesty solo material originally cut decades ago but finally officially released last year on Ace Records.

Similarly evocative of its title is “Bouncing Ball,” with its buoyant recoil, while “Herb’s Mood” swaps liveliness for languor, Hardesty’s playing unfolding at the gradual pace of a strip tease.

“I’m lonely, so lonely,” Walter “Papoose” Nelson moans on “It Must Be Wonderful,” one of two tunes here with vocals, as Hardesty’s sax mirrors the longing in Nelson’s voice, haunting the song like the memory of a faded love.

Throughout the album, Hardesty’s chameleonic playing changes with the setting.

He’s a man of many moods.

Still, there’s a jovial nature to much of his repertoire, and the same could be said of Hardesty himself.

He’s a warm, engaging presence, still spry and quick with a smile.

“I love music, man,” he says. “Communicating with people is a happiness.”

In recent years, Hardesty has battled Bell’s palsy, a form of facial paralysis, which hampered him for a time.

But for the most part, he has overcome it.

He had to.

There are more shows to play.

“Never stop. Never stop.” Hardesty says, repeating the words like a mantra. “That’s my life.”

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at

jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476.