Punk Rock Bowling traces punk from past to future

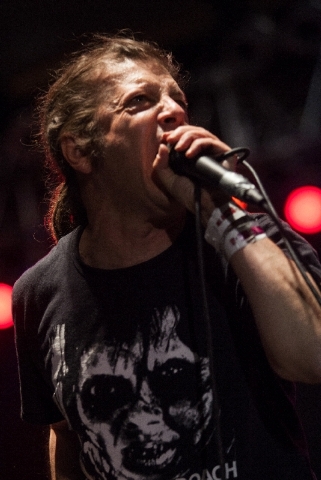

The tone deaf dude who fired off his words like an assault rifle encapsulated the sentiment of the weekend in a manner as blunt and indelicate as his meat cleaver of a singing voice.

“I don’t like the society out there, but I like the society in here,” D.R.I. frontman Kurt Brecht announced from the stage at the Punk Rock Bowling music festival Monday, surveying a field of snow-cone colored coifs and sweat-saturated denim. “Can’t get along with those other people.”

He wouldn’t need to, for four days at least, when punks young and old, though mostly the latter, formed a dust-huffing enclave in downtown Vegas. Thousands strong, they took over a gravelly patch of land near the El Cortez, which was transformed into the site of a boozy family gathering, a graveyard of beer cups and a punk rock bazaar stocked with skull-shaped jewelry and baby T-shirts that read “My mom’s tattoos are cooler than your mom’s.”

This us-versus-them mentality that Brecht spoke of has long served as punk rock’s crankshaft.

When the music was sired in the mid-’70s, it was youth versus parents, teachers, cops and other authority figures trying to tell them what to do, an act punishable by death — or in its place, two minutes or so of righteous sonic snarl.

But something has happened in the ensuing three decades: those once-angry kids have become parents, teachers, cops and other authority figures.

Now, they’re looking less for a fight than a good time, and that’s what Punk Rock Bowling is all about.

Inhabiting an outdoor festival area for three days and various clubs for four nights, Punk Rock Bowling, now in its 15th year, has become both a celebration of punk’s past as well as a glimpse into its future.

There are the younger upstarts, such as the ineffably frenzied Retox, who scorched the stage Monday with motoric, speed-of-sound hardcore, purposefully letting feedback swell in between songs and then sheathing through the din with frontman Justin Pearson singing so hard, his face turned tomato red and a vein bulged from his temples.

The band that followed, Belgian oi! outfit Funeral Dress, was more indicative of the weekend, however, with beer-basted anthems that sounded like soccer chants exhorting punk rock as a lifestyle, which they’ve done for well over two decades now.

This contrast from one group to the next underscores how the festival has become something of a punk rock genome map, tracing the music from the present back to its origins.

On Saturday, one of L.A.’s first punk bands, The Weirdos, held court with equally melodic and convulsive critiques of well-adjustment and nuclear armament, followed by British scene forebears The Damned, who alternately scalded and seduced with speedy sing-alongs and death pop dirges that served as a fitting musical accompaniment to the setting sun.

Decidedly more volatile were The Damned’s equally wizened countrymen in the Subhumans.

Fast and threadbare, their politically charged songs were just vehicles for the message they were intended to impart, a means to an end, a delivery method, so simple, so direct, so effective.

“I wanna complain ’cause I think I like it,” singer Dick Lucas brayed Monday during “Internal Riot.” “I get deranged when it’s all gone quiet.”

Aside from this kind of punk rock orthodoxy, there were outliers at Punk Rock Bowling, such as new wave pioneers Devo, who thrilled Saturday. They made electronic-based music feel warm-blooded and visceral, with songs that warned of overconsumption and decline backed by a large video screen where images of fresh fruit were contrasting with depictions of the female form, symbolizing temptation and our inability to resist it.

“How many punks here tonight believe that devolution is real?” singer-bassist-keyboardist Gerald Casale asked. “We all grew up D.I.Y.,” he continued, referencing punk’s do-it-yourself origins. “Now it’s just do-it-to-yourself.”

Speaking of excess, the tongue-in-cheek, denim-fetishizing Norwegian rock hedonists in Turbonegro, which performed Sunday, are as indebted to the blustery swagger of the Rolling Stones and AC/DC as they are to the hook-heavy charge of the Sex Pistols and the Ramones.

Guitarist Knut “Euroboy” Schreiner dressed and played like The Who’s Pete Townsend, leading the way as the band perspired beer and pelvis-thrusting odes to sex and pizza alike.

“This is biblical. This is like Sodom and Gomorrah,” singer Tony Sylvester gushed approvingly between tunes, taking in the hard-partying crowd. “This is beautiful, in a kind of bacchanalia, Satanic way.”

Perhaps the most eagerly anticipated performance of the weekend, though, was a festival-closing set from Flag, a band made up of former members of L.A.’s Black Flag.

“I’m going to explode!” frontman Keith Morris, a dreadlocked lightning bolt, howled during “I’ve Had It,” and the crowd eagerly waited for the group to do just that, though it took some time.

Flag was like a slow-burning fuse, inching toward detonation. In the same way that some athletes need to first break a sweat to really get into the game, Flag lacked urgency during an opening suite of “Revenge,” “Fix Me” and “Police Story.”

But by the time the band got around to standards such as “My War” and “Gimme Gimme Gimme,” it was all business, the songs bullying and confrontational, with gnarled rhythms hammered into shape by drummer Bill Stevenson, who attacked his kit like a kid swatting at a pinata.

One of Black Flag’s direct descendents, Bad Religion, headlined Sunday.

The group rocketed forward with a kind of brainy belligerence, having served as a super collider of social commentary and pop hooks for more than three decades now. “Sometimes the songs go by so fast,” singer Greg Graffin noted.

As do the years.

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476.

REVIEW

Who: Punk Rock Bowling

When: Saturday-Monday

Where: Ogden and Seventh Street

Attendance: 5,000 a day, estimated

Grade: A