Photographer pieces together revealing photos, stories

Everyone has a story. But not everyone can tell it.

Enter photographer Charles Mintz, whose camera captured 170 people holding the “Precious Objects” they hold dear.

Grace, then 89, posed with the beloved stuffed canine she’s had since she was 4. The plush dog stayed by Grace’s side during her childhood bout with scarlet fever — and came back from the dry cleaners “not quite so plump and fuzzy as before, but she’s still my beautiful and faithful Trixie.”

Loli held letters, written by the mother she never knew.

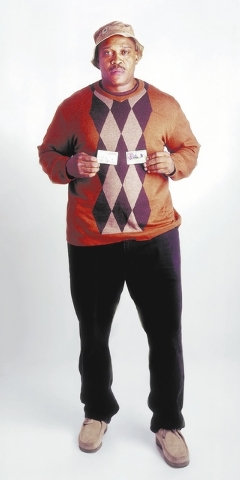

Trevis brought his current library card — and the card he carried 25 years ago, which identified him as a prison inmate.

Their portraits, and 21 others, form the heart of Mintz’s “Precious Images,” currently on display at two venues: Las Vegas City Hall’s second-floor Chamber Gallery and the Charleston Heights Arts Center, which hosts a meet-the-artist reception from 6 to 8 p.m. Friday.

Although the City Hall gallery is “a small space,” with room for seven images — accompanied by the subjects’ hand-written explanations — there’s “a lot of traffic,” Mintz says. “The hope is that people will go to the arts center” to see the remaining 17 portraits, he adds.

“There’s something sentimental and personal and universal” about the “Precious Objects” exhibit, observes Jeanne Voltura, gallery director for the city of Las Vegas, who responded positivitely when the Cleveland-based photographer contacted her about a possible Southern Nevada showcase. “I thought his work would talk to just about anybody — and everybody.”

Initially, Mintz had no intention of focusing on the people who bring “Precious Objects” to life.

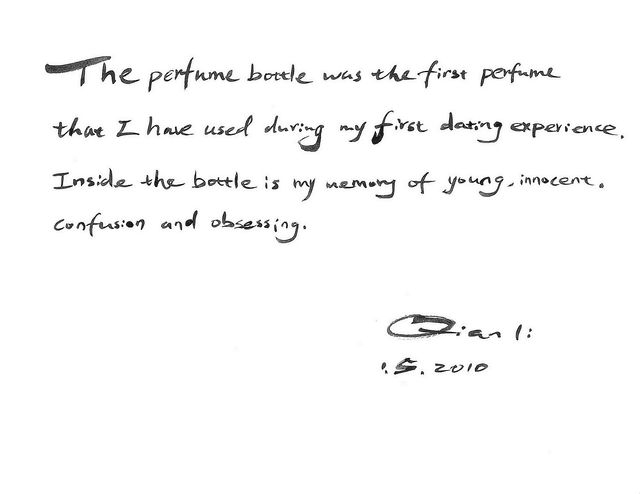

When he photographed Qian “holding a perfume bottle from her first romance,” Mintz planned to use the image as part of a photographic “commentary on consumerism,” he recalls during a telephone interview.

Following Qian’s portrait session, Mintz began “sneaking into department stores and photographing perfume bottles,” he says — until he realized that “nobody gives a damn about my criticism of consumer culture.”

So Mintz refocused, remembering a previous project, featuring his autistic son holding albums of Polaroids he’d taken over many years, the shots featuring the albums “with just a little bit of his hand” showing.

Over the next year and a half, “Precious Objects” took shape.

Some subjects — “friends and families of friends” — posed for Mintz in his Cleveland studio.

From there, the photographer traveled to Atlanta, Columbus, Houston, New York’s Long Island — and the African American Museum of Nassau County in Hempstead, N.Y. — to capture portraits and stories.

At the museum, Mintz asked potential subjects to sign up and was amazed how many “people just showed up — absolute, complete strangers,” he says.

Among them was Trevis, who wrote a poem about “how far he had come — and how difficult it is to get people to see you,” the photographer remembers.

In the poem, titled “My I.D.,” Trevis writes, “I want them to know me. To feel me! To help heal me, rebuild me. Who am I? Photo 1-2 or three? Am I locked up or free? A stick or a tree? It’s my I.D., but which is me?”

As Mintz focused on his subjects and their “Precious Objects,” the photographer was struck by their compelling memories, from a woman “who brought the dress she was adopted in” to another volunteer who “brought his father’s teeth,” along with “a wonderful story.”

Overall, “I was astounded, at the end, at how people would come before me, a complete stranger,” to share their stories, he admits. “People trusted the process remarkably well.”

Yet, to stay true to that process, Mintz had to set aside some of the aesthetic principles and techniques he’d learned during his decades-long quest to be a photographer.

Now 65, Mintz was inspired to pursue photography during a weeklong workshop he took 35 years ago. But he spent his professional life in the corporate world, working for companies that made plumbing hand tools and industrial control systems. That is, until he decided to make his hobby a full-time pursuit.

As “Precious Objects” took shape, Mintz “didn’t do a lot of posing or relighting or anything you would do in portraiture,” he explains, noting that he had to violate “a lot of the rules of good photography, the accepted canons of how you photograph people.”

Fortunately, “I didn’t need for each one to be an expression of my aesthetics,” he acknowledges. Although “there’s a certain amount of the mastery of the image you want to exhibit,” Mintz notes, “I can tell you, the fellow who brought his inmate card was going to be in this exhibit, even if the film was blank.”

A book documenting the entire project features six pages of thumbnail photographs including every participant; about 30 subjects are featured in greater detail, with their written statements accompanying the portraits. (Mintz’s book will be available at Barnes &Noble’s Rainbow Boulevard location during the exhibit’s Las Vegas run.)

“When I look back at how it started, I feel kind of stupid, because the end result was so compelling,” the photographer says, remembering the impact of a portrait session with a subject who “comes in and hand-writes a beautiful story.”

Under normal circumstances, Mintz would have set up flattering “Hollywood” lighting to take her portrait. But under the rules he set for “Precious Objects,” it wasn’t necessary.

After all, Mintz says, “I’m not trying to prove how brilliant I am with a camera. I’m trying to tell good stories.”

Contact reporter Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.

Preview

"Precious Objects"

7 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Mondays through Thursdays through April 10 in the Chamber Gallery, second floor of Las Vegas City Hall, 495 S. Main St.

12:30 to 9 p.m. Wednesdays through Fridays and 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays through April 23 at Charleston Heights Arts Center, 800 S. Brush St.

Free (702-229-1012 or 702-229-6383; www.artslasvegas.com)