OSHA previously investigated ‘Ka,’ no violations reported

Aerial artist Sarah Guillot-Guyard never doubted safety procedures at “Ka.”

And, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration revealed Wednesday, the Cirque du Soleil show had no safety violations as of its last inspection.

“She told me that Cirque puts so much emphasis on safety, it was ridiculous,” recalled Marc Gitelman, who runs NV Tae Kwon Do, where Guillot-Guyard’s two children take martial arts classes.

Guillot-Guyard died after falling about 90 feet during a performance of “Ka” on Saturday night.

The Las Vegas Cirque shows that OSHA inspected include: “Ka,” at MGM, in February 2009; “Viva Elvis,” at Aria, from 2009-2010; “CRISS ANGEL Believe,” at Luxor Hotel and Casino, in 2010; and “Zumanity,” at New York-New York, from 2010-2011.

“CRISS ANGEL Believe” was inspected again in May and remains an open case.

Violations found in the inspections, released Wednesday, varied in severity and included problems with “explosives and blasting agents,” “emergency action plans” and “guarding flow and wall openings and holes.”

Of the closed Cirque cases — a mix of scheduled and unscheduled inspections — “Ka” was the only show to have no violation listed.

“You fall off something in Paris, you hit the dirt,” Guillot-Guyard told Gitelman, enthusiastic as she compared safety procedures she experienced in France with those at Cirque, a company where she loved to work.

Guillot-Guyard, 31, fell near the end of the show during Saturday’s second performance.

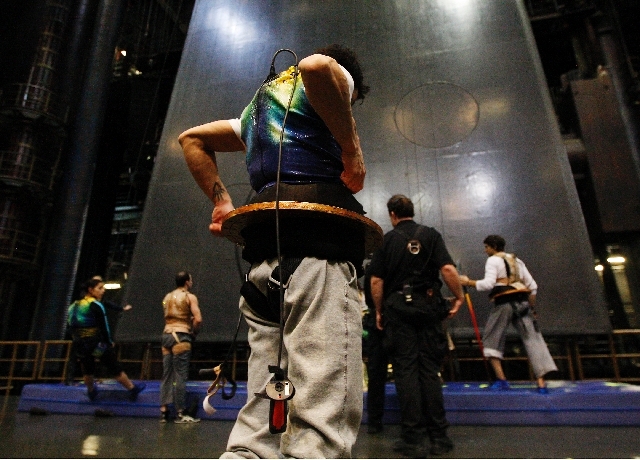

During a battle scene at the climax of the show, performers rappel along a vertical wall while suspended on wires nearly 120 feet in the air.

Each performer wears a harness equipped with hand controls to help steer the guide wires.

This was the first onstage fatality during a performance in Cirque du Soleil’s 29-year history, according to spokeswoman Renee-Claude Menard.

Safety procedures have taken center stage since Guillot-Guyard’s death, prompting many in the Cirque community to rally behind the company.

Menard emphasized that the company’s security measures have always been above-standard and that no extra precaution was necessary at other shows.

“We know we always take safety and security seriously,” she said. “We only ask that we take extra care in evaluating our performers’ state of mind.”

Michael Montanaro, a former Cirque employee, echoed Menard’s sentiments, crediting the company for being overly cautious with performers’ safety.

“They had people who were measuring the friction of the floor, dragging friction barometers, so that no one would slip on the paint they were using,” said Montanaro, a choreographer for “Varekai” from 2001-2002.

He said riggers deliberately stop rehearsals “if it goes past a certain point … if it goes too dangerous.”

Those close to Guillot-Guyard attended a private vigil for her Wednesday evening at The Fit Labs, where she taught Cirquefit classes.

“We didn’t know Sarah the ‘Ka’ performer here. That was probably the furthest thing for us,” said James Wong, co-owner of The Fit Labs. “We knew Sarah as a friend, here every Saturday, teaching her class. That’s what we’ll remember most about her.”

Cindy Jackson, a mother whose son is a Cirquefit student, helped organize the vigil.

“She was a force,” Jackson said. “She would tell kids they were the next generation of Cirque performers.”

Katy Tollefson of Illinois-based Hall Associates Flying Effects, a supplier of flying system packages for stage productions, said malfunctioning equipment is extremely rare.

Tollefson said a winch motor, such as the one used at the time of Guillot-Guyard’s death, is controlled by a computer system or a person operating a joystick. The control system tells the winch motor to move the performer up or down, left or right.

“Some people prefer a computer control that you can program so the movement is always the same. Some prefer a human using a joystick who’s looking at a human with their hands,” she said.

A winch can weigh up to 500 pounds and be as large as four cubic feet.

Winches can be anchored to the stage floor or rigged to anything above the stage, depending on the production’s needs, with the cable attached to a harness worn by the performer.

Tollefson said situations become dangerous when safety protocols aren’t followed.

“Different companies have different standards,” she said.

All cables are rated by a breaking strength, the amount of weight a cable can safely hold.

Tollefson said some productions suspend people or items whose total weight is too close to a cable’s breaking strength, typically marked on the cable.

But Tollefson emphasized that the total stress put on a cable does not solely come from the weight of an aerialist. It also includes the force of the aerialist’s acceleration as he or she swings and spins across the stage.

Tollefson said it is well known in the industry that Cirque employees are safety conscious.

A study published in 2009 in the American Journal of Sports Medicine examined injury patterns and rates in circus acts. The first of its kind, the study compiled data provided by Cirque du Soleil on show-related injuries from 2002-2006.

Injury rates for acrobats were slightly higher than the rates for musicians and nonacrobatic artists, generally because acrobatic acts involved more risk, according to the study.

The study found that 1.1 percent of acrobats suffered injuries in a five-year period, compared with 1.5 percent of competing female gymnasts, which the authors found to be the sport most like circus acts.

The study concluded that “most injuries in circus performers are minor, and rates of more serious injuries are lower than for many National Collegiate Athletic Association sports.”

Kristin Wingfield, a former bungee trapeze artist in “Mystère,” said that even with Cirque du Soleil’s rigorous safety procedures, performers independently check their rigging and equipment.

“Yes, it is a dangerous activity, so we take extra precautions to alleviate those fears,” said Wingfield, now a primary care sports medicine specialist.

“Human error is a huge factor. Riggers check you; you check you; you check it again.”

An OSHA investigation into Guillot-Guyard’s death began Monday, and no information will be released until the investigation is closed.

Wingfield said accidents happen, “but then again, it’s one in 30 years. If you think of the number of shows and the number of acts, it’s so rare.”

Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Colton Lochhead contributed to this story. Contact reporter Melissah Yang at myang@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0491. Follow her on Twitter @MelissahYang.