‘Making a Murderer’ underscores shift in documentary filmmaking

It bears the attention-grabbing name "Making a Murderer," and even if you're not watching it yourself, you've probably found it difficult to avoid during the past few weeks.

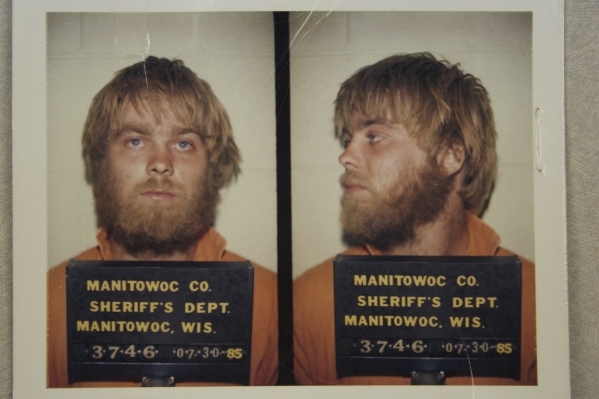

"Making a Murderer," a 10-episode documentary series that has been streaming on Netflix since Dec. 18, is the story of Steven Avery, who spent 18 years in prison on a sexual assault conviction, was exonerated and then subsequently was convicted of murder and sent back to prison, where he's serving a life sentence.

The series has prompted not just unusually heated pop culture buzz for a documentary series, but even a petition to President Obama to free Avery, whom supporters believe was railroaded by law enforcement officials. (The U.S. Department of Justice has noted, however, that the president can pardon only persons convicted of federal crimes; Avery was convicted in a state court.)

Reality series — the documentary's downmarket cousin — long have been beloved by American viewers. But how has, of all things, a serious documentary been able to break through the nearly infinite universe of broadcast, cable and streaming offerings to become a must-watch program?

Start, maybe, with its always tempting, provocative subject matter: namely, murder, crime and people doing (or allegedly doing) nasty things to one another.

Bob Benedetto, professor and lead instructor in the College of Southern Nevada's video and film program, hasn't caught "Making a Murderer," but was an avid watcher of "The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst," a similarly buzz-worthy documentary series that ran on HBO last year about accused murderer Robert Durst.

"I was so absorbed in it," Benedetto says. "And the ending — I don't want to spoil it for you, but it was so extraordinary."

Durst was a compelling character, and compelling characters — whether good or bad — can provide an incentive for viewers to follow a documentary. Then, Benedetto says, compelling storytelling will help to grab, and retain, viewers' attention.

Toward that end, documentary filmmakers today are apt to use storytelling and narrative techniques that would be surprising to anybody whose idea of a "documentary" is a boring succession of talking heads. Today, the use of re-enactments, archival footage and music can help to make a documentary seem akin to a fictional film.

In fact, Benedetto found stylistic touches in "The Jinx" that he also found in the HBO dramatic series "True Detective."

" 'The Jinx' had the exact same kind of structural format as 'True Detective,' " Benedetto says, as well as a credit sequence that resembled that fictional series and shared storytelling techniques.

Documentaries that become widely buzz-worthy tend to have "a high-concept, headline-type story, and I do think that stories that involve crime and murder are right at the top of that list," Benedetto says. "And the ones that rise above in that genre are the ones that have something unique about them."

It also maybe noteworthy that "Making a Murderer" and "The Jinx" were presented in episodic form. That may have helped to attract viewers who might have balked at committing an uninterrupted 90 minutes or two hours to a single presentation.

In addition, that serial format can allow a filmmaker to delve into a complicated story in more depth. "The Jinx" could "never have been done in just two hours," Benedetto says. "It really needed the full scope."

From a storytelling standpoint, breaking up a documentary into serial format also offers viewers "a cliffhanger every week," Benedetto says, serving as an incentive to continue watching.

This not really new but, perhaps, resurgent style of serial documentaries does share DNA with reality TV series. Francisco Menendez, chairman of the film department at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, recalls how such series as "Cops" — and, on the seamier side, such series as HBO's "Taxicab Confessions" — helped to make recognizable to a wider audience the use of a broader palette of storytelling techniques in documentaries.

Today, documentary filmmakers are using literary and cinematic devices found in fictional narratives, he says. "We've found a lot of ways to deliver this content in a compelling way using certain narrative techniques and old documentary techniques, and synthesizing those."

Viewers, meanwhile, increasingly have become comfortable with this evolving version of the documentary form, he says. "I'm not sure that 30 years ago, people would have looked at a serialized documentary at all. But we're becoming used to it and accepting it and making meaning of that content."

Las Vegas filmmaker Stan Armstrong's documentaries include "The Misunderstood Legend of the Las Vegas Moulin Rouge," "The Rancho High School Riots," "Invisible Las Vegas" and three documentaries about Native Americans and African-Americans during the Civil War.

Armstrong (www.desertrosefilms.com) says he has employed some of the techniques — re-enactments using actors, for example — now commonly seen in serial documentaries.

"I think it's actually been going on for a while," he says. "But with the information age today and the creativity of producers and directors, it's just a little bit more exciting.

"I think there are so many programs out there today that a documentary filmmaker has to be different, has to be innovative, to get viewers watching his or her stuff."

However, some of the techniques filmmakers are using and which viewers have come to expect can be expensive, particularly for self-supporting, independent filmmakers like Armstrong.

For example, he says, "in my film about the Moulin Rouge, I thought about using re-enactments, (until) I found out how much it would cost with costumes and the period pieces."

And, it's a simple reality that many worthy documentaries never will receive the public buzz that a "Making a Murderer" or "The Jinx" will.

Armstrong's current project, "City Within a City," is a documentary about the Las Vegas Paiute tribe. He's also completing work on historical vignettes that will run on Cox cable during Black History Month. Because his work focuses on historical and cultural topics — often with a minority focus — Armstrong concedes that appearing on the national pop culture radar "is harder."

But, he says, "I don't want to sell out. I know that murder sells. I know that sex sells. As a director and a producer, I know this. But I think one has to stay true to himself or herself and stick to what you do best."

— Read more from John Przybys at reviewjournal.com. Contact him at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com and follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.

Like Neon Las Vegas on Facebook: