The rise and fall of the Oath Keepers, born in Las Vegas

Editor’s note: Reporter Jeff German had started writing this story before he was killed earlier this month. His colleague has finished his reporting.

For Stewart Rhodes and the Oath Keepers, an extremist organization born in Southern Nevada, the 2014 standoff with law enforcement authorities outside Cliven Bundy’s Bunkerville ranch was a chance to make a splash within the anti-government movement.

The former Las Vegan claimed to be serving as a messenger for Bundy’s activist son Ammon, providing instructions to those flocking to the militia encampment, according to the extremist watchdog group the Southern Poverty Law Center.

At the time of the high-profile Nevada showdown, Rhodes said he had 35,000 members, mostly former and current military and law enforcement officers, dedicated to preparing for what they believed was an eventual all-out conflict with a government determined to establish a totalitarian regime known as the “New World Order.”

Dozens of right-wing militia members from across the country answered a call to arms to help the Bundys thwart a roundup of family cattle that federal authorities alleged were being allowed to illegally graze on government land. Bundy maintained his ancestral family had settled on the arid basin long before the government took possession.

When U.S. Bureau of Land Management officials aborted the roundup on April 12, 2014, out of fear of bloodshed, it was viewed as a victory for the militias and emboldened their extremist leanings.

But it was not a victory for the Oath Keepers.

Rhodes and his members had fled the scene after picking up unfounded rumors that the Barack Obama administration was planning to attack the militia base with high-tech drones. The Oath Keepers were mocked and branded cowards by the other groups.

The public rebuke left Rhodes devastated, according to his estranged wife Tasha Adams.

“He just fell apart and went into depression after that,” Adams said. “He couldn’t sleep for days at a time and never got over it.”

The rise of extremism

Yet less than eight years later, Rhodes’ organization soared to the top of the conspiracy-filled world of the anti-government movement. The Oath Keepers were at the center of one of the nation’s boldest attacks on democracy — the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol Hill riot aimed at overturning the election of President Joe Biden.

Rhodes, 57, is now paying the price. He and several of his group’s members are standing trial Tuesday in Washington, D.C., on seditious conspiracy and other charges tied to the violent insurrection despite recent failed attempts by Rhodes to delay proceedings.

Some former members of the Oath Keepers have said Rhodes started to care more about the money than the mission. And anti-extremist experts say the Oath Keepers have gone into a downward spiral, with a dwindling membership while Rhodes sits behind bars.

This comes while other right-wing organizations, such as the Proud Boys, whose members also are charged in the Jan. 6 riot, are still growing, extremism experts said.

At least 1,000 Nevadans have paid membership dues to the Oath Keepers, according to a recent report published by the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism. That includes six serving in the police or military, two Nevada candidates for public office and a sitting Nye County Commissioner.

Adams, who has been in a heated divorce battle with Rhodes since they separated in 2018, said her husband had delusions of grandeur when he founded the group in Las Vegas in 2009.

Coming to the aid of the Bundys in 2014 fit into his plans to establish himself as a leader in the anti-government movement, she said.

“He went there thinking he was going to be the grand marshal of everything,” Adams said. “But he was never going to be the main guy there. It was always going to be Cliven and Ammon Bundy.”

A Las Vegas beginning

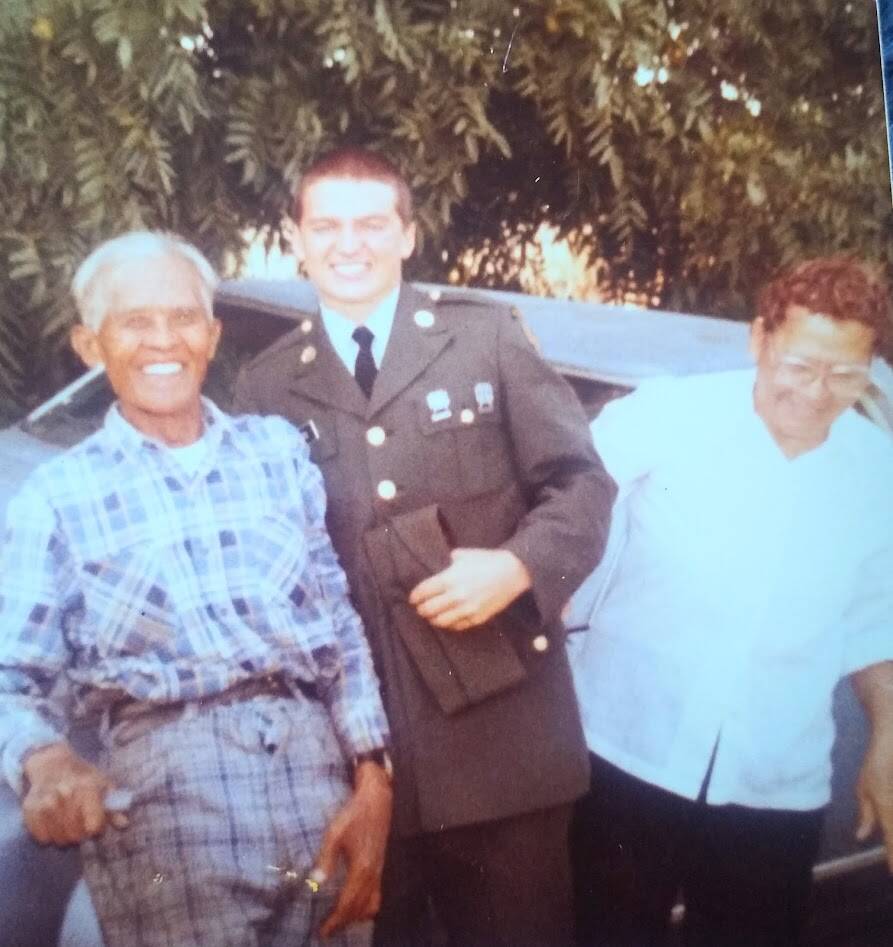

Rhodes, an Army veteran who graduated summa cum laude from UNLV in 1998 with a bachelor’s degree in political science, started the group as a nonprofit organization, records show. By that time, he was a Yale University Law School graduate.

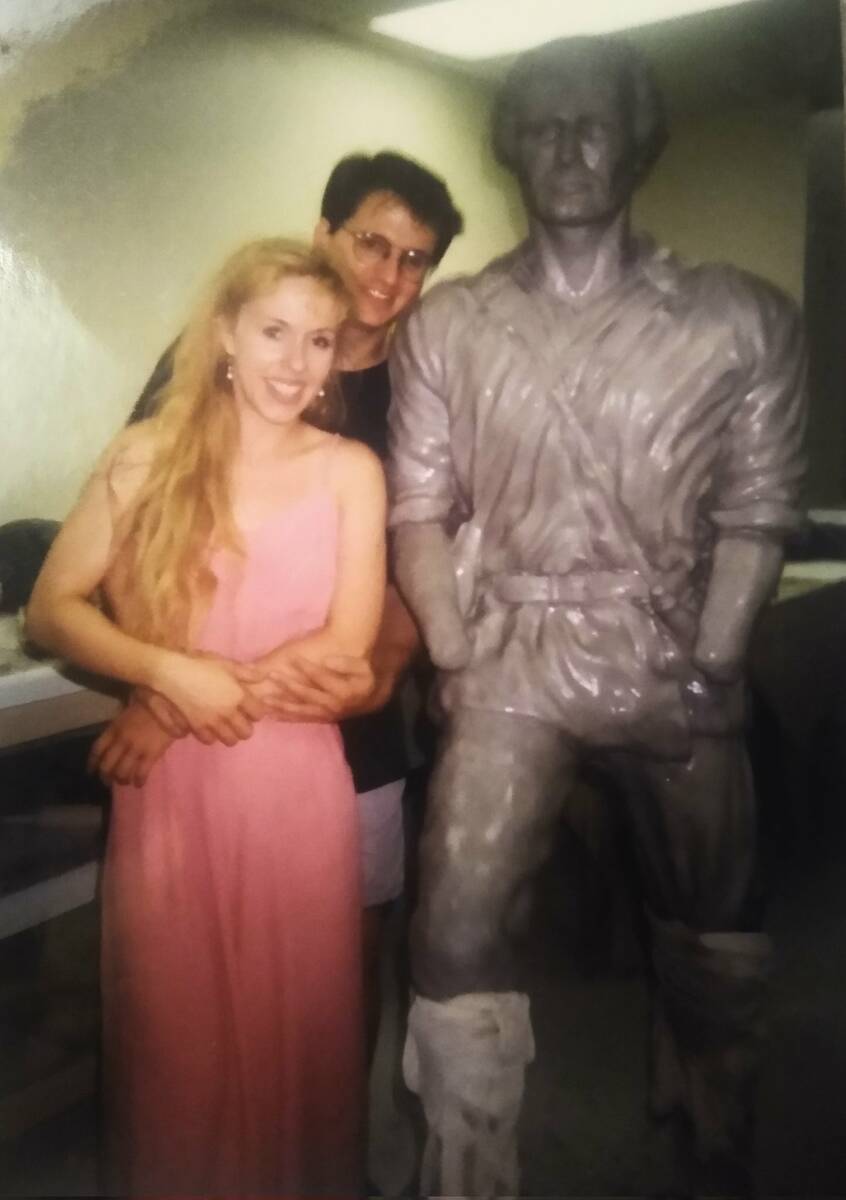

Adams and Rhodes met in Las Vegas, where she was a ballroom dancer and he worked at a gun shop and as a valet at Binion’s. They married in 1994 and share six kids.

Rhodes had pressured her to quit college and strip at Club Paradise to support the family while he was in school, Adams said.

After Rhodes worked for congressman Ron Paul of Texas and clerked for an Arizona Supreme Court justice, the couple returned to Las Vegas.

It made sense to form the Oath Keepers here, said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

“Nevada is a place that has always catered to individualism,” he said.

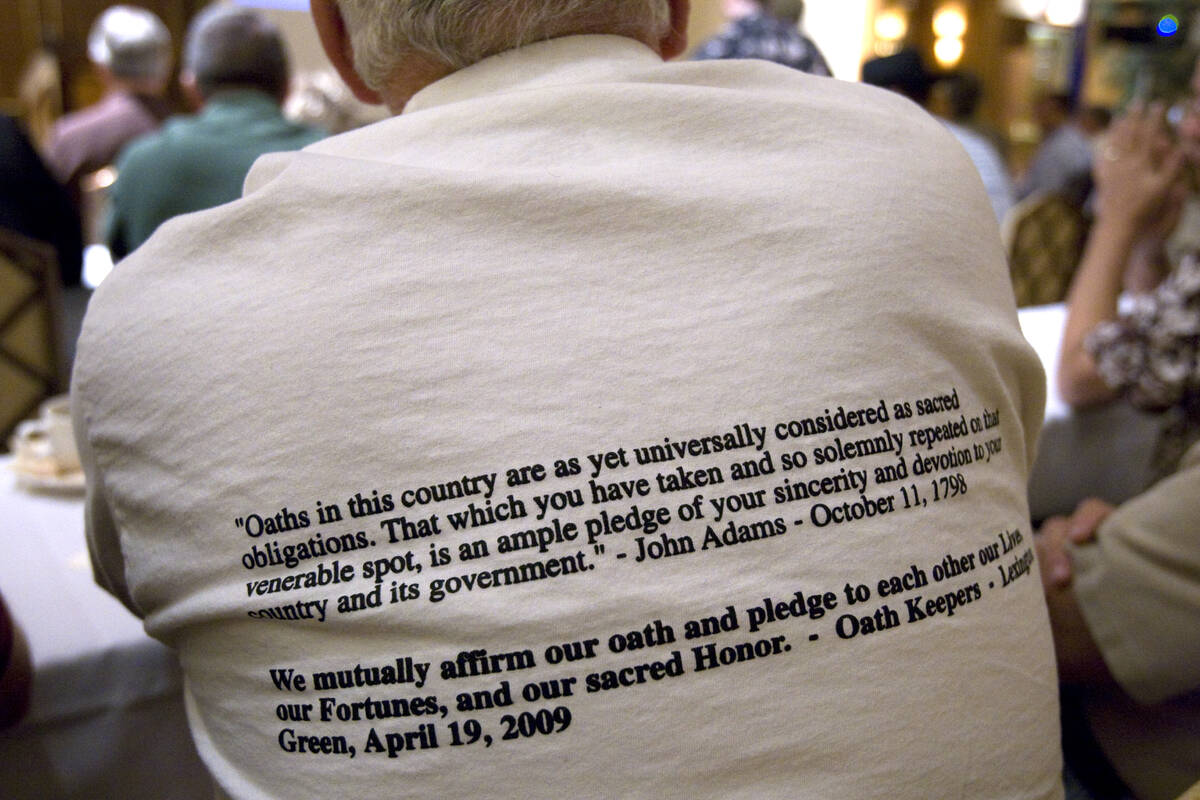

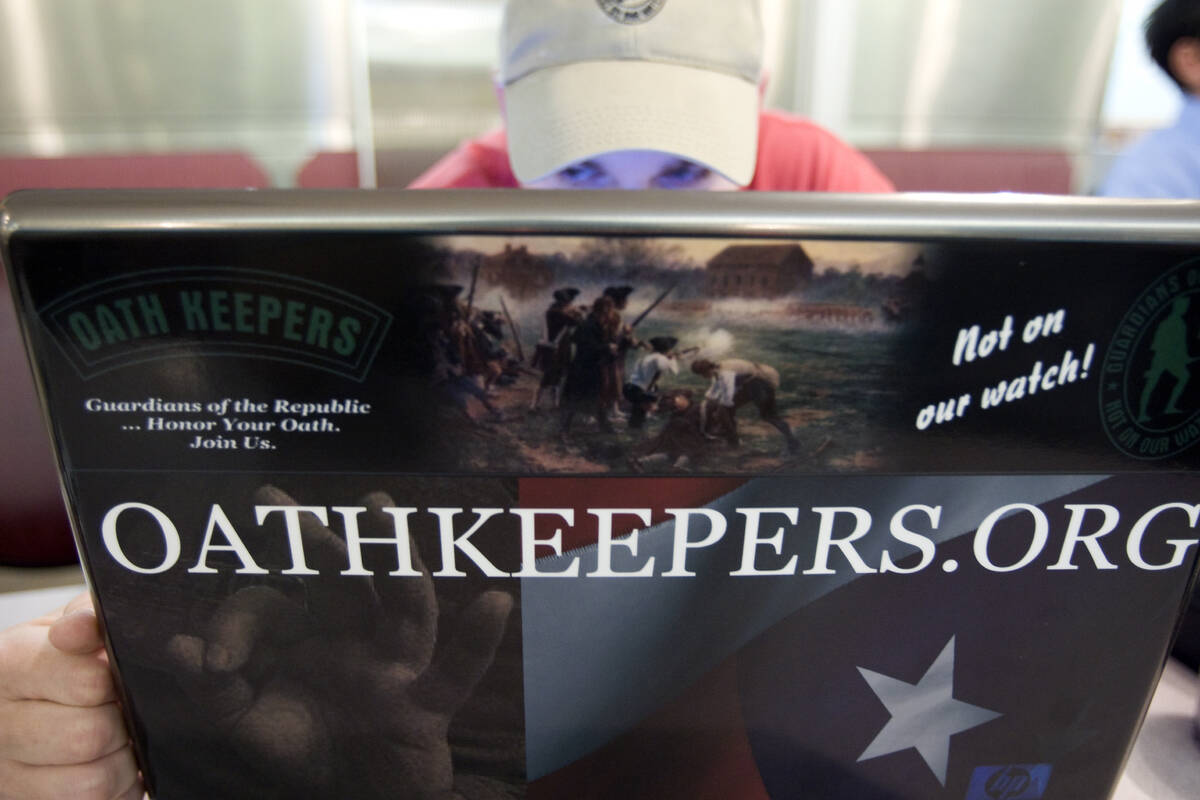

And Rhodes was riding high on the popularity of the Tea Party movement at the time. In its first meetings, Oath Keepers vowed to support the oaths they took to defend the U.S. Constitution.

They followed a list of 10 “Orders We Will Not Obey,” which compiled perceived threats by the federal government, such as plans to impose martial law and seize Americans’ weapons.

The group drew controversy from the start. A Review-Journal article from 2009 described the Oath Keepers as either “strident defenders of liberty” or “dangerous peddlers of paranoia.”

“The whole point of Oath Keepers is to stop a dictatorship from ever happening here,” Rhodes told the newspaper at the time. “We say if the American people decide it’s time for a revolution, we’ll fight with you.”

Rhodes’ attorneys did not return calls and emails for this story.

‘The ACLU for everyone’

Rhodes’ message appeared to resonate within the law enforcement community.

Metropolitan Police Department officers attended Oath Keepers meetings, according to Adams and newspaper archives, from the beginning. Adams said officers would pull Rhodes over just to say thank you.

“Vegas was a very huge part of Oath Keepers starting; Las Vegas Metro was a huge part,” she said.

Metro did not respond to requests for comment.

In the early days, Adams handled much of the Oath Keepers’ operations, filling T-shirt orders and answering hundreds of emails a day. In the first few weeks, the blog went viral and raised $70,000, she remembered.

“The tagline was, ‘this is the libertarian version of the ACLU’ or ‘the ACLU for everyone,’” Adams said. “It really had the exact opposite views when it started as when it ended.”

Those on the ADL list of Nevadans who have paid dues include Southern Nevada Assembly Republican candidate Stan Vaughan, Independent American Party candidate for governor Edward Bridges and Republican Nye County Commissioner Donna Cox.

When reached by phone, Vaughan hung up on a reporter, stating, “I’m not going to hear any more of this absolute nonsense.” Cox did not return a phone call or email.

In an interview, Bridges described Oath Keepers as an educational group and said he has not been involved since 2015. He said he was first drawn to the Oath Keepers because it appealed to his firm belief in the U.S. Constitution.

“It was a very good organization,” he said. “I think it’s been hijacked by people who do not like America.”

An inflection point

The biggest inflection point for the Oath Keepers came at Bundy ranch, experts say. It gave Rhodes the stage to recruit and heightened his stature within the anti-government movement.

“It was the point of no return after that,” Levin said. “These folks were ready to battle the federal government there before they got on the path to the Capitol.”

Bundy recalled in an interview how Rhodes and his members suddenly departed his ranch after the talk of the drone attack spread through the groups.

“Most of his camp just picked up and left in the middle of the night,” Bundy said. “Some of the other militia people were mad at them and called them chickens, but my thinking was that they still came to support us during the standoff, and we were thankful for that.”

The Oath Keepers accounted for about a third of the militia present during the armed standoff with federal officers, said J.J. MacNab, a fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

And though some members pointed guns at law enforcement on the highway bridge, Rhodes was not among them.

“He liked to think of himself as George Washington,” MacNab said. “Stewart makes orders; he doesn’t do what he orders people to do.”

In a video posted later, Rhodes would describe the ordeal as “this close from being a gunfight.”

In the end, five defendants connected to the standoff pleaded guilty before trial, several were acquitted of all counts and some were convicted of lesser charges.

Excessive spending and fundraising

Rhodes would go on to spearhead a vigilante justice movement, with the Oath Keepers providing voluntary and sometimes illegal armed security during some of America’s most tense events.

With each cause, he shored up more dollars for the organization.

“You can’t really have the militia world without grifting,” MacNab said.

Adams remembered that Rhodes would spend thousands of dollars on custom-made knives, travel, weapons and rental cars. So much so that some people started to distance themselves because of excessive spending and fundraising.

Greg Whalen, a 56-year-old disabled Navy veteran and former Oath Keeper, was at Bundy ranch in 2014. He said he first took notice of the grift when Rhodes ordered an exorbitant amount of food on the group’s dime, while the other members spent their own time and money on the cause.

“They may have started out for the right reasons, but Stewart Rhodes turned out to be a rat,” said Whalen, who recently moved away from Nevada. “He fired up a lot of guys under the guise of patriotism.”

The more membership dropped, the more desperate Rhodes became, and the more he was willing to share the stage with other extremists with different ideologies, such as white supremacists, according to experts and Adams.

“He’s this walking grenade,” Adams said. “And that was the beginning of the end.”

Attack on the U.S. Capitol

The end came after Jan. 6, 2021.

Though the Oath Keepers’ constant messaging revolved around gun control, it became further fueled by the nation’s unrest, COVID-19 restrictions and online venting.

Real estate agents, business owners, professionals, police officers, military members and veterans all joined the attack on the Capitol, alongside hard-core extremist groups, experts said.

The mob of hundreds in Washington all shared some of the same grievances, particularly the false belief that the election was stolen from former President Donald Trump.

Adams said she recognized the Oath Keepers when she saw footage of a military formation going up the steps in full gear.

The trial Tuesday will center around Rhodes, who authorities say was the ringleader in the Oath Keepers’ monthslong plot to use force to overthrow the government.

Experts say that as the evidence in the trial is disseminated, the fractured Oath Keepers will likely rebrand themselves or resurface in local organizations that have less baggage.

“It’s like hitting mercury with a hammer. It doesn’t all disappear,” Levin said. “There will be other trains coming down the railroad, even if the Oath Keepers get derailed.”

German was a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team. Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.