Curiosity about rage leads Las Vegas man to correspond with criminals

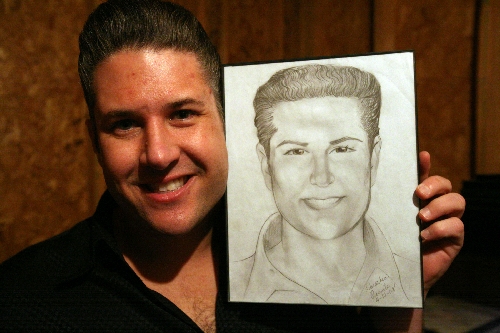

Tony Ciaglia talks to serial killers.

He even calls some of them -- Joseph R. Metheny, Ken Bianchi, David Gore, the late Arthur Shawcross -- his friends. Ciaglia, 34, knows that may horrify you. He knows you probably wonder how or why he would befriend convicted killers who brutalized, raped, murdered, tortured and even cannibalized dozens of victims.

But when Ciaglia started writing to serial killers in 2006, he was desperate. He felt a level of depression, despair and rage that few would understand. So he reached out to those who might. In the process, he changed his own life.

A book, "The Serial Killer Whisperer" (Touchstone, $24.99) by Pete Earley, about Ciaglia and his correspondence with serial killers, hits store shelves Tuesday. It details the reasons why Ciaglia started writing to his prison pen pals and the friendships he forged with three: Shawcross, Metheny and Gore.

NBC has purchased the rights to Ciaglia's story.

"I knew I could take a lot of heat for calling these people friends because of the heinous things they did against society," Ciaglia says. "I wouldn't want them living next door to me, but the pen pal relationship, I look at them like they're friends."

Ciaglia moved to Las Vegas with his parents, Al and Chris, and brother Joe, in 1997. The family left their longtime home in Dallas, looking for a fresh start in a town that wasn't big on being judgmental.

Tony needed it. Ciaglia is tall with dark hair and soulful eyes. He is friendly and handsome. He looks perfectly normal.

He is not.

At 15, while swimming at summer camp, Ciaglia was hit by a jet ski. He suffered a severe head injury that put him in a coma for days. When he awoke, he had to once again learn how to walk, talk, eat, tie his shoes. His parents were overjoyed that they had their son back. Not much was known about brain injuries in 1992, Al Ciaglia says, so they thought life would eventually return to normal.

"It's been a long road," Al Ciaglia says. "We weren't given anything, no lessons on what to expect or how to protect him. Chris and I came to a realization that, what the neurosurgeon told us was true, (recovery) would be a marathon. Nothing would be the same again."

The injury to Tony's brain affected the areas that control emotions and decision-making. This made Tony impulsive and depressive and he suffered severe and sudden mood swings as well as outbursts of rage and anger. He also tends to be obsessive and compulsive.

"People don't realize what it's like, you go out with your son and you're constantly worried," Al Ciaglia says. "You're constantly worried and on alert. I don't want to know what my insides look like, probably terrible. In the old days, you just prayed that he didn't perceive that people were looking at him the wrong way. He would walk into a room and if he saw two people chatting and then glance at him, he would think they were talking about him. That's just a terrible way to live."

In the first few years after the accident, Tony occupied himself with an Elvis Presley hobby. During his coma, Chris and Al Ciaglia played Elvis music to Tony. He developed an affinity for the music and started singing. Eventually, he began performing as an Elvis tribute artist, even playing a few gigs in Las Vegas during the late 1990s.

The music was instrumental to his recovery, Chris Ciaglia says. But even that couldn't address his mood swings and rage. Even the cocktail of drugs he takes doesn't cure all of his issues. Because he can't work a steady job, he has a lot of time on his hands and a lot of time to ruminate.

This is where serial killers come into their lives. One day, Tony's psychologist said, "You need to get a hobby."

"I wasn't real crazy about it, at first. I hoped he would take up stamp-collecting," Chris Ciaglia says. "But his father had an interest in criminology and so did Tony. It was just good to see him involved in something. Of course, we had no idea it would turn into this."

He mailed about 40 letters to serial killers around the world, asking if any of them would trade stories about their lives and how they became killers with his stories about growing up in Sin City. He also hoped to ask them if they had felt the way he did, full of rage and depression. Though a drug, Seroquel, helped dampen his rage and anger, he still wanted to understand it. Tony received 32 replies.

Over the years, he has amassed thousands of letters and more than 300 pieces of artwork from serial killers. The mother of Ken Bianchi, one of the Hillside Stranglers, gave Tony her son's bronzed teddy bear. Collectors would pay a lot of money for some of the items Tony owns but he says he would rather burn his collection than sell it.

"What I share with a lot of the killers is the anger issues, the depression," Tony says. "I've spent months not being able to leave this house. While they lived in a physical prison, I lived in a mental prison."

While Al and Chris Ciaglia initially balked at the idea of their son corresponding with known killers, they soon thought of it as a good thing. It occupied Tony's time and pulled him out of a severe depression.

"He would have these outbursts of rage. He was so bad, we didn't know if he would make it back again," Al Ciaglia says. "He was on the verge of suicide."

They have always wanted to tell their family's story, Al Ciaglia says, because they want to help others with traumatic brain injuries. That is the underlying message in their story.

"Tony wants to help with cold cases," Al Ciaglia says. "If he can help, it would really make him feel great. But the bottom line, he wants to get the word out about brain injury. There are people out there struggling with brain injuries. He wants them to know, they're not alone, there are medications that can help."

Contact reporter Sonya Padgett at spadgett@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @StripSonya on Twitter.