Alzheimer’s caregivers seek to remember the good times

Inside the Solari Hospice on Thanksgiving Day, Alzheimer's disease eats away at 82-year-old Virgil "Gene" Quinn's brain.

Where he's at, why he's there, who he's with ---- most of the time the retired meteorologist, who worked for the Atomic Energy Commission at the Nevada Test Site, does not know.

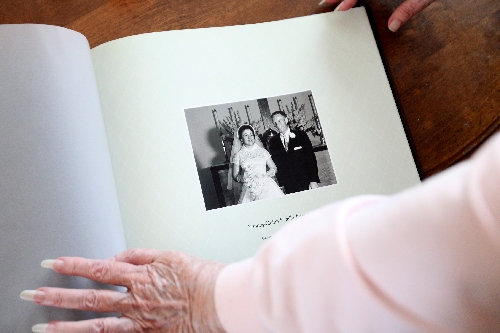

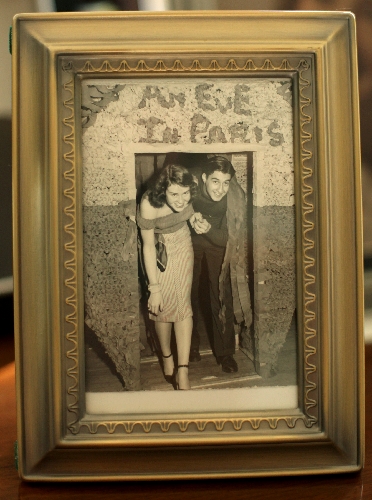

Patsy Quinn, his wife of 55 years who cared for him in their Las Vegas home for more than three years before his condition recently worsened, registers the terror in the eyes of the love of her life as a nurse starts to give him a dropper full of medication.

It is the same kind of terror she saw a year ago when she entered their bedroom one night to check on his condition and he started to flail and struck her, thinking a stranger had broken into their home. That painful experience has forced her to try to get sleep in a living room chair for more than a year.

"The disease turns you inside out, doesn't it, Gene?" she said, touching him gently on the forehead.

The Quinns' oldest daughter, Andra, was afraid her mother would die from the stress of caregiving.

"She's so tired," she said. " She gets up a lot at night to check on him. She felt only she could give him the best care. I'm so glad she finally agreed to get some help."

The role of the at-home caregiver for Alzheimer's patients is so stressful that it is not unusual for the caregiver to die before the patient, said Albert Chavez, Southern Nevada regional director of the Desert Southwest Chapter of the Alzheimer's Association.

"Trying to take care of someone 24 hours a day who is often no longer himself isn't easy," Chavez said, noting that 80 percent of Americans take care of loved ones with the disease at home.

Several Southern Nevadans caring for relatives agreed to share slices of their lives with the Review-Journal, hoping that their experiences increase awareness of Alzheimer's impact and spur public officials into providing more support for those who take care of loved ones in their homes.

They stressed that while caregiving can be trying, there also were many times when they still found joy with their loved ones. When they still could talk, they might talk about children, or sports. When they could still walk, they went for long ones every day. Sometimes just the feeling of the sun would bring smiles.

In Nevada alone, the Alzheimer's Association places the number of caregivers at more than 132,000 ---- men and women providing nearly 151 million hours of unpaid care.

"They're not trying to hurt you, honey," an exhausted 77-year-old Patsy Quinn whispered as she stood by her husband's bedside while the hospice nurse squeezed out medication.

"He's scared," she said as her husband, a University of California, Los Angeles graduate whose care is complicated by emphysema, blood clots, colon cancer and failing kidneys, clenched his jaw and refused more medicine.

Quinn had often taken her barely mobile husband to 10 doctor's appointments in a month. Once he lost his balance at home and fell on her, which left her fighting to breathe until she could move him.

As her husband lost much of his memory, thinking and language skills to Alzheimer's, Patsy Quinn watched as agitation, fear and anger filled what had been a gentle soul, the man with whom she raised three children, who even in the early stages of his disease could talk for hours about the futures of their children and grandchildren.

Though Quinn is generally upbeat, flashes of frustration came out recently at her home, as she recalled how she and her husband had hoped to travel more in their retirement.

"I'm so sick of hearing about the golden years," she said. "Screw the golden years."

She still finds it hard to believe the wonderful, good man who helped nurse her back to health from breast cancer could have struck her or that he would often push her away and tell her to "shut up and get the hell out of here" as she tried to clean him and give him medication.

"It's the disease making him act so awful, not him; people need to know that," she said as she caressed the cheek of her husband as he slept at home in his favorite chair. "It steals who you are."

On the morning of Nov. 26, Virgil "Gene" Quinn died at the hospice center. His tearful wife said she is thankful that he is out of pain and that in the hours before his death he picked up her hand from the pillow and kissed it.

"He remembered what we had," she said.

WHISPERS IN THE NIGHT

In the living room of their Pahrump home, Tim Wombaker watched the Notre Dame-Stanford football game. In a bathroom, Toni Wombaker brushed her 69-year-old mother's teeth.

"Do you have to go to the bathroom, Mom?" asked Toni Wombaker, sounding very much like a mother trying to toilet train a child.

Yvonne Jensen, in the late stages of Alzheimer's disease and helpless to do nearly anything by herself, smiled and shook her head.

"I don't know if she recognizes me now or not," the daughter said of her mother as they walked out of the bathroom hand-in-hand.

"My mother spent most of her career life in banking. ... A bank robber came into her branch with a handgun demanding money. He actually held the gun to my mom's head while screaming at her to give him money or he would blow her (expletive) head off. ... As I sat at a drive-in movie theater late one summer night in 2011 ... I realized my mom was being robbed again. ... What is slowly being stolen from my mom is her memories. ... What does life really mean if you don't have memories? What would your life be like if you didn't remember ... your children?" - Toni Wombaker's journal

Though she was supposed to go back to teaching fifth grade once her youngest child entered kindergarten - her four children are either in elementary or middle school - Toni Wombaker, 40, works instead as both the primary caregiver for her children and her mother since Yvonne Jensen was diagnosed with Alzheimer's two years ago.

The family makes do financially on her husband Tim's salary as a school principal as well as a $1,500 monthly stipend her mother receives from a late friend. That stipend has allowed Wombaker to bring personal attendants into the home.

Wombaker said that before her mother was diagnosed with the disease - family doctors had said for years she was just depressed ---- her mother's bizarre behavior in Tonopah, where she then lived, put tremendous stress on her marriage.

And Wombaker became angry at her mother.

"Often she wouldn't return my calls," Wombaker said. "That wasn't like her. And once, Mom's debit card didn't work and I found out she was $1,000 overdrawn. Remember, this is a woman who was a banker most of her life. I found she had been donating to 28 different organizations."

Wombaker's mother, generally fastidious, would wear six necklaces at once and clothes that didn't match.

And she'd tell the same story, including one about her son going to hunt in Alaska, four times in the same conversation.

One story she'd repeat to complete strangers was one she had never shared in public before - about how she lost a child when the doctor's forceps crushed her baby's skull.

"It was completely inappropriate," Wombaker said. "I got so worried about her that I neglected Tim and my children."

Only when she talked an official at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health into an immediate appointment in 2009 - the center didn't have formal appointments available for weeks - did the frantic Wombaker find out what she suspected, that her mother has Alzheimer's. She and her husband then decided to buy a home with an apartment, allowing her mother to be part of the family, but also affording her privacy.

After my mom's diagnosis and I knew what was wrong with her, my frustrations toward her were replaced with understanding. ... My anger at her was replaced with compassion because I finally understood she couldn't help her actions and the decisions she had made. ... I have already grieved the loss of the mom I once knew. ... This doesn't mean I love my mom any less, it is just a different love. We have different roles and different lives now."

Wombaker often views PBS children's shows with her mother while they hold hands. As she watched her mother wander aimlessly around their home, Wombaker said it would be difficult for her to place her mother in a home.

"I just think I care about her more," she said.

Her mother suffered a mild stroke recently and had to be hospitalized briefly.

Wombaker now has hospice medical professionals that Medicare pays for visiting the home on a regular basis.

To help other families who have a loved one with Alzheimer's, Wombaker and her family have made a video that discusses the challenges of the disease. It has been viewed thousands of times on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JbMuhxsNLIk).

When her mother has bowel movements in her pants ---- which is common among Alzheimer's patients in the latter stages of the disease ---- Wombaker said her mother is terribly embarrassed.

She'll sometimes verbalize her feelings by crying out, "It is horrible," or, "Oh, it's nasty."

"My heart aches for her," Wombaker said as she sat in her mother's small apartment, one that is adorned with her mother's oil paintings and quilting.

It is only when her mother has an embarrassing accident that Wombaker said the woman who is generally so sweet and smiling changes.

"I have to take her to shower, and she gets angry with me and it's the only time she wants to hit me. She's wanted to spit on me then, too, but she spits in a trash can instead."

Though her mother hasn't had conversations with people in some time ---- in church she stares off into space - until recently she would often wander the house at night talking to herself.

Wombaker wept as she remembered what she calls "whispers in the night."

"I miss the haunting whispers. Even though I know they were a sign of the confusion and torment that must be going on in her mind, I miss hearing her voice and knowing that she doesn't seem to be trying to work it out any more. It makes me frightened. I feel as though time is short, days are numbered. I may be wrong, but I am realistic to know that as the whispers in the night fade, so does Mom."

MONEY CAN DO ONLY SO MUCH

That stare.

Three months after his wife's death, 72-year-old Jerome Snyder has flashbacks and still sees it in his mind's eye.

It haunts him, her frozen focus on something he could not see, a behavior so often part of Alzheimer's.

Diagnosed at 59, Diane Snyder had what doctors call early onset of the disease that strikes most people in their mid-60s or later.

Though his wife's 12 years with the disease generally saw her with a mild temperament, Snyder said that changed in the last year, when she became more argumentative and loud, more childlike.

But it is that stare, which accompanied the disease, that he most remembers in caring for her.

A multimillionaire entrepreneur who searched the world for an Alzheimer's cure, Snyder knows his finances ---- his Bingo Palace became Palace Station ---- allowed him to care for his wife of more than 30 years far differently than most people experience.

He hired a live-in caregiver, someone to handle grooming and toileting and meals and tantrums.

"I can't imagine the stress of doing it all by yourself," he said.

Still, he fed his wife, who used to love fixing dinner for guests, after she forgot how to use utensils.

They held hands and night after night watched the same taped PBS concerts that she most enjoyed because they were always new to her.

He tried to engage her with longtime friends, but they were now strangers that frightened her.

He talked to her about the places they once dreamed of living around the world, destinations they now would never make.

Generally, she spoke very little, just fixed him with that curious stare that somehow seemed, at the same time, both empty of, and full of, thought.

"I buried myself in my work," Snyder recalled. "I worked harder to compensate for how I was feeling."

Diane ended up sleeping in the caregiver's room because she would often get up and wander, affording her worried husband little sleep for the workday as he repeatedly got up to find her.

Sometimes, though, he'd still hear her murmuring as she wandered.

Her face, so lovely when animated, would float before him with that frozen stare that frightened him.

"I always wondered what she was thinking, if she had something to tell me about Alzheimer's," said Snyder, who is now on the board of Keep Memory Alive, the fundraising arm of the Ruvo Center. "I still wonder."

CAREGIVER OFTEN AT RISK, TOO

It's not uncommon to find 81-year-old Jean Georges, a Ruvo Center library volunteer at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health who nearly died while taking care of her husband with Alzheimer's, successfully counseling spouses of those with the disease to enroll in a free program at the center, one designed to increase the coping skills of caregivers while also decreasing their stress.

Learn from me, she tells them.

"I don't want them to make the same mistakes I did," she said.

It was in 2003 that Georges started to see a difference in her husband, Leonard Georges. A longtime successful businessman, his investment decisions started to seem strange.

Even though someone wanted him to invest almost all the money for yet another wedding chapel in town ---- and then run it even though he was recovering from strokes ---- that sounded great to him.

So did real estate deals that were long on promises and only sure to make someone else money.

Never, said Georges, did she suspect a medical problem. Maybe, she thought, he wanted to take more risks now that he was comfortable in retirement.

Nor did she think there was a medical reason for his accusing her of failing to write letters that he had never asked her to write, or for his asking questions repeatedly or for leaving the garden hose on all night as he watched TV.

What had been an idyllic marriage of almost 60 years changed. Instead of talking issues through, they argued.

She said that if her husband didn't get his way he became agitated, but she chalked it up to his being burnt out after working 16- and 17-hour days for years.

Family doctors said his behavior was a normal part of aging.

Arguments with her husband escalated when he didn't want to bathe, or tried to pay laborers $1 after trimming 23 trees.

The conflict took a toll on Georges, and she went to the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., for a checkup. She couldn't sleep or eat. Her nerves were shot. After she arrived, she had a heart attack.

"I realize all the time how lucky I was to have it there," she said.

The Mayo doctors told her if she wanted to live, she could no longer care for her husband ---- the stress would kill her.

Tests on her husband proved he had Alzheimer's.

Georges tells spouses of those with Alzheimer's that she wishes physicians were as aware of Alzheimer's when her husband had the symptoms as they are today. Couple that with the availability of a caregiver support group and she's sure that she and her husband would not have had all their arguments.

And she might not have had what doctors called a stress-induced heart attack.

It's also possible she would not have had to put Leonard in a long-term assisted living facility.

"I would have never argued with my husband if I had known he had Alzheimer's," said Georges, who became a Ruvo Center volunteer to help ensure that other people don't go through what she has. "You're taught that in those caregiving classes ---- it's a golden rule. It wasn't his fault that he had a reality different from mine. That was the Alzheimer's talking."

LOSING EVERYTHING

Sherry Ables struggled to speak.

"It looks like we're going to lose our house," she said, sobbing as she sits in the living room of their well-kept Las Vegas home.

"It's just terrible that a guy can work for 40 years and then just like that, through no fault of his own, he loses what he worked for. He supported his family, didn't drink on the way home, and now he won't have his roof over his head."

Her husband, James, was diagnosed last year with early onset Alzheimer's at age 58.

He had been the main breadwinner as the couple raised two boys.

"I still can't believe this is happening," a fidgeting James Ables said. "I'm too young."

A construction worker who lost his job in the bad economy ---- Sherry also lost her administrative assistant position - James took a job in housekeeping for a casino.

It wasn't long before he lost that job for forgetting to put keys away and by not scheduling employees to cover a shift.

That behavior went along with what his wife had been seeing. He would go to Lowe's and forget why he was there. He couldn't remember what they talked about the night before.

"It wasn't like him at all," she said. "He was always a stickler for detail. But friends and family always told me he was just stressed. And I wanted to believe, of course, that nothing seriously was wrong."

Sherry made her husband go to doctors, saying she'd always stick by him, but he had to try to help himself.

"I thought he might have a tumor," she recalled. "Alzheimer's wasn't on my radar. I thought it was only for old people."

The diagnosis floored Sherry Ables. Through the Alzheimer's Association, she found Deb Newton, who had lost her husband to early onset Alzheimer's. She was starting a support group.

What Sherry Ables heard was scary. Joe Newton went from being a lively 45-year-old to a wheelchair and finally bedbound. He weighed only 63 pounds when he died at age 58.

"I thought James and I were going to have some time together with the kids out of the house," Sherry Ables said. "But then he gets this disease where he couldn't even get unemployment insurance because he can't work."

Today, James Ables goes into the kitchen and can't remember why. He is starting to lose his balance and fall.

With no money coming in as Sherry Ables worked to get her husband on Social Security disability, all their savings were used. For two people, they received $16 a month in food stamps. They sold jewelry, whatever else they could find to sell.

She kept trying to get a job, but soon noticed if she wasn't around, James wouldn't get out of bed or eat.

"I'd have to hire somebody to watch him, and then what I make as an administrative assistant would be gone," she said.

Soon he was staring into space, or yelling.

"It's never been like him to yell but he's got a flash temper now," she said. "If I redo something he's done, just replace a pot on the patio, he'll yell at me and say that I don't think he's good for anything."

James finally received disability benefits, but it doesn't cover the $1,000 a month house note and household expenses.

They're behind on their mortgage.

Sherry Ables prays she can get someone to rent rooms in their house to save their home.

"I go into the restroom three times a day to cry," Sherry Ables said. "I know the worst thing is going to be when I lose my husband. But for right now we just can't lose our house.

"I could start all over in a small apartment but James can't. I think he knows he can't handle anything strange. He said to me the other day, 'All I want is we get to stay in our home.' It makes me feel like such a loser that I can't make that happen. I'm trying. I'm really trying."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

Alzheimer's disease: A Rising Storm

The Review-Journal presents a series about Alzheimer's disease and its impact on society, today and potentially in the future.

• An overview outlining the prevalence of the disease and efforts by families to cope with it and by researchers to treat and cure it

• The financial impact of the disease on families and society

• Alternative forms of care, from day care to assisted living and nursing homes

Upcoming:

Tuesday

• Identification and treatment of Alzheimer's disease

Wednesday

• Debate about the benefits of testing for Alzheimer's

Thursday

• The state of Alzheimer's research and what is needed in the future

FINDING HELP

These are local organizations that help people with Alzheimer's disease and their families. Some accept volunteers.

Alzheimer's Association, Desert Southwest Chapter, Southern Nevada Region

The association offers general information, support groups, educational programs, referrals and opportunities to volunteer.

Address: 5190 S. Valley View Blvd., Suite 104, Las Vegas, NV 89118

Phone: 702-248-2770

24-hour Helpline: 800-272-3900, operates seven days a week, in 140 languages

Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health

Address: 888 W. Bonneville Ave., Las Vegas, NV 89106

Phone: 702-331-7054

Appointments: 702-483-6000, Option 2

Information about services and programs for caregivers and families: 702-483-6023

Information about enrolling in a clinical trial: 702-685-7073 or brainhealth@ccf.org

Donations: Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Philanthropy Institute, 702-331-7052

Volunteer: 702-331-7046

Keep Memory Alive: 702-263-9797