Laser eliminates dangerous plaque caused by peripheral artery disease

By January, Rick Carter couldn’t walk 100 yards without feeling severe, cramplike pain in his calves and feet.

Even at rest they hurt. They were also often cold and numb, sometimes tingled and were unnaturally shiny.

Doctors had a difficult time detecting pulses in the diabetic’s feet.

The 69-year-old retired trade association executive knew the lack of blood flow to his lower extremities could eventually mean the death of body tissue and amputations. And soon.

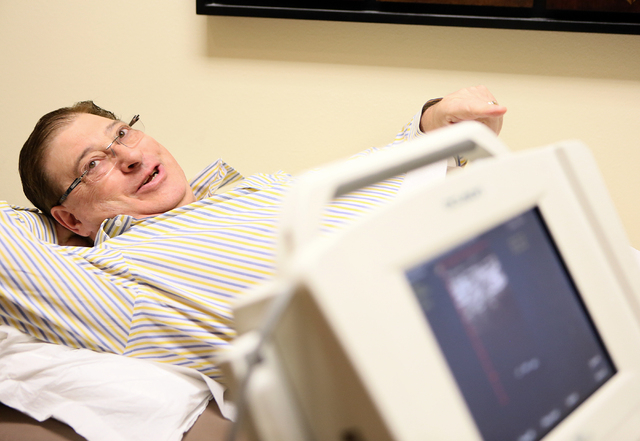

“I’m so glad I had the laser procedures done,” Carter said recently as he lay on an exam table and discussed the health problems that brought him to Dr. Ken Shah’s Henderson office. “My legs feel fine now. I can walk wherever I want. He fixed my problem.”

As Shah conducted a follow-up examination (he said the pulse in both of his patient’s feet “was strong”), he talked about Carter’s “problem” — peripheral artery disease, or PAD, which experts estimate affects as many as 17 million Americans.

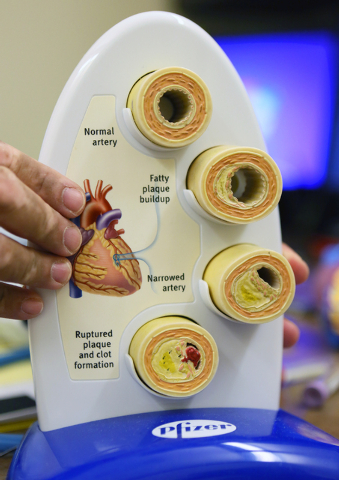

In peripheral artery disease — often associated with high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, sedentary lifestyle and aging — cholesterol and fat plaque blocks circulation to vital arteries, often in the legs and feet.

Far too often, Shah said, the symptoms Carter complained about, particularly lower-leg pain, is misdiagnosed and primary care doctors make referrals to orthopedic surgeons, nerve specialists and podiatrists.

“I’ve seen people actually go through surgeries they don’t need,” Shah said, shaking his head, “and by the time they get a correct diagnosis, the only thing left to do is amputate.”

To help determine how well a patient’s blood is flowing, experienced clinicians use the ankle-brachial index, a painless, inexpensive exam, to compare blood pressure in a patient’s feet to the blood pressure in his arms.

Normally, the ankle pressure is at least 90 percent of the arm pressure. But with severe narrowing, as in Carter’s case, the pressure was much less than 50 percent.

Then further tests are done to confirm PAD.

Around Valentine’s Day, Shah put Carter in Desert Springs Hospital for two days so he could perform laser atherectomy procedures, which use a laser to vaporize blockages and restore blood flow in leg arteries.

Shah knew Carter had developed the most serious form of PAD — critical limb ischemia, in which there is pain even at rest, and gangrene, death of body tissue, could come soon.

Less than two years earlier, after initially being evaluated for nerve and orthopedic conditions by other physicians, Carter was referred to Shah with leg pain. At that point, his leg problems weren’t as serious as something else Shah found during his initial consultation — Carter had blockages in his coronary arteries.

“He didn’t have symptoms but he was in real danger of a heart attack,” Shah said. “We had to take care of that first.”

Shah would place stents, expandable metallic tubes, in Carter’s heart to improve blood flow.

Often, Shah said, patients with leg blockages also have heart blockages.

“It’s definitely not something you want to overlook,” said Shah, a solo practitioner who envisioned the vascular institute he opened in 2002 as addressing peripheral arterial and venous disease (legs, kidneys, arms), coronary artery disease (heart) and cerebrovascular disease (stroke) prevention.

In 2013, as Shah tried to correct Carter’s leg problems through diet, exercise and medications, Desert Springs Hospital Medical Center bought the technology that would allow a new laser to be used on leg blockages.

“We were very fortunate to get the best technology to use,” he said.

Before the laser technology, balloon angioplasty was required to push aside blockage from a vessel. Doctors complained that the balloon often tore the vessel and injured the artery, stimulating the artery to renarrow.

A study involving patients with high risk of limb loss had found that 93 percent of patients did not have to undergo amputations six months after initial laser treatment.

The study also found no adverse events related to the device and 77 percent remained free of any further lesions after 12 months.

“We definitely didn’t do the laser on a whim,” Carter said. “I made lifestyle changes in diet and exercise but my legs just got worse.”

Carter was surprised that during the laser procedures, for which he received conscious sedation, there was no pain.

“The only thing I ever felt was a little tickle on my right leg around the knee cap,” he said. “There was a huge blockage that they lasered out there and it only felt like someone putting a feather on my kneecap. I was in la-la land but I could hear them talking about what they were doing.”

Shah did Carter’s left leg on Feb. 15 in about 90 minutes and his right on Feb. 16 in about twice that time, each day beginning the procedure by inserting a small fiber-optic catheter, which is connected to the laser unit, through a femoral artery in the groin.

The laser catheter is slowly moved by Shah, who can see where it’s moving because of radioactive dye put in Carter’s legs, through the artery until it gets to a blockage. When the catheter reaches the occlusion, it transmits short, pulsed bursts of ultraviolet energy through the catheter, penetrating the blockage.

The laser catheter moves slowly through the occlusion, about 1 millimeter per second, dissolving the blockage into tiny byproducts that are smaller than a red blood cell and quickly absorbed into the bloodstream.

“I could see the catheter going down my leg like a high-tech video game,” Carter recalled. “They’d zap the blockage — it was like ‘Star Wars.’ ”

Even Grant Abitria, the supervisor for the Desert Springs catheter lab where the procedures were performed, found himself getting excited by the removal of the blockages.

“It’s just very dramatic,” he said.

Soon after his Sunday procedure was over, Carter left for home. And three days after his blockages were cleared, the dressings placed at the femoral artery entry points for the catheter procedures were removed.

That same week he was walking pain-free.

A few days later, he knew for sure the blood was moving well to his feet.

“My toenails were growing,” he said. “It had been a long time since they did that.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.