Organization working to boost organ donation among minorities

Arlett Valencia crosses another date off her mental calendar, counting the days she has been waiting for a kidney and pancreas transplant.

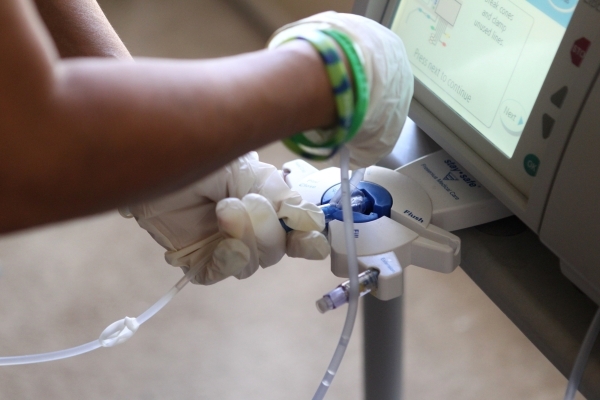

"It has been 1,156 days," she says as she sets up her daily dialysis — the machine that has kept her alive since her kidneys started to fail. "If you would have told me three years ago I would still be waiting, I wouldn't have believed you."

Valencia is not waiting alone.

In Nevada, there are 558 people waiting on an organ transplant list, including 76 African-Americans, 119 Hispanics, 78 Asians and 12 American Indians.

Alma Rodriguez, multicultural coordinator with the Nevada Donor Network, says many of these donations are tied to other health issues prevalent in minority communities such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes.

But as Valencia, 36, has discovered, despite being affected disproportionately, the number of minorities who register to be donors is surprisingly low.

There are 880,450 registered donors in Nevada, but registration is low among minority communities.

Rodriguez says the organization currently doesn't have the number of registered donors broken down by ethnicity but is working to find out.

Though donations can be given and received from anyone provided that person is a match, Rodriguez says because of genetic markers people have a higher chance of being a match if they are from the same ethnic background.

Throughout the years, various organizations such as the Nevada Donor Network have put on events and used marketing campaigns to raise awareness about organ donations in general.

But Rodriguez says there needs to be a different approach when talking to minority communities.

"You can't use the same message in the Hispanic or African-American community," Rodriguez says. "You almost have to do it one-on-one so you can talk about this sensitive matter."

With the help of diverse volunteers — a mixture of donor families, recipients and those still waiting — Rodriguez is hoping to address the issue of low registration head-on. Each one talks about his or her story regarding organ donations.

Crystal Hill is a donor mom who talks about the importance of people discussing donation issues with their families early. Hill's 18-year-old son, Jesse, died in 2013 and donated his organs. Though they had the conversation when he was younger, she didn't know he and his brother registered when they got their driver's license.

Until volunteering with the Nevada Donor Network, she had no idea that donations were low in the African-American community.

"I'm white, but my son is black," she says. "I didn't know he would be filling a greater need."

She also never knew just how much of a reach it would have.

Hill says through organs, eyes and skin, her son's donation helped more than 80 people and saved five lives.

Cliff Conedy, who is 63 and African-American, talks to people from a different perspective. Seven years ago, he received a heart transplant that saved his life.

Though leading an active and healthy lifestyle, Conedy had no clue his genetics could cause problems.

In 1994, he was diagnosed with idiopathic cardiomyopathy, a hereditary defect. Even when his doctor told him a heart transplant might be possible, he never would have imagined it.

His heart looked normal until 2008.

"I started experiencing heart issues," he recalls.

Within a few weeks, he was admitted to UCLA Medical Center and placed on a transplant list.

"At that point, my heart was only functioning about 5 percent," he says. "I was in the hospital for four months."

Because his weak heart was deteriorating rapidly, the doctors installed a ventricular assist device to support his heart and help bring his other organs back to a functional level, which would make him eligible for a transplant.

"Five days later, I received my transplant," he says.

During his recovery process, Conedy knew two things: He would spend the rest of his life raising awareness about the importance of organ donations and he would meet his donor family.

He discovered though his donor, who was a 32-year-old white male, wasn't registered, the family signed off to have his organs donated after he died.

"That was Sept. 9, seven years ago," Conedy says.

Along with his heart, Conedy says the donor was able to save other lives through the harvesting of his kidney, pancreas and lungs.

"Not to mention the people he helped by donating his skin and tissue," he adds. "I haven't met all of them, but I met one of them who got his kidney and pancreas."

He still remains connected with the family, attending fundraisers and events through various organ donation organizations.

He has since kept his promise to share his story.

"I will share it with anyone willing to listen," he says. "I was given a second chance at life because someone said yes."

Together, along with Valencia who is still waiting for her donations, the volunteers are confronting the cultural and even religious barriers that keep people from signing up to donate.

Rodriguez says over the next few years, the organization plans to build a higher, and more diverse, network to do outreach for minority communities.

"We've already added more African-American donor families and recipients to our volunteer network," she says. "We have added Hispanic and Asian recipients, too."

Rodriguez and Valencia, who are both Hispanic, know firsthand the difficulties that come with talking about health issues in general, let alone organ donations, in their community.

"I'm Mexican so I understand it is something we don't talk about," Valencia says. "In my family, we think that if you talk about dying, it's going to happen soon."

In a lot of Hispanic communities in particular, Rodriguez says, there is a misconception that donating organs is against their religion.

"There are few religions where this is against," she adds.

Hill, who is Christian nondenominational, says she had the same religious question when she started researching donations years ago.

During a church service when the pastor was taking questions from the congregation, Hill asked about organ donations.

"I wanted to know what our religion said about it," she says.

In the future, Rodriguez says the organization plans to partner with faith-based leaders to get the word out about organ donations.

Another misconception, Rodriguez says, is that people think they wouldn't be a viable candidate because of age or unhealthy lifestyle choices.

But other than organs, donations can be vast, ranging from tissue, tendons, bone and even corneas.

One unfounded fear she has heard is that people wouldn't be able to have an open-casket funeral if they donate their organs.

Conedy says another misconception he has heard is that if a doctor knows a person is a donor, he or she won't do everything possible to save the patient's life.

"This is probably more prevalent in the black community," he says.

Hill says doctors take great care to make sure they do anything and everything to save a life. If a patient dies and is an organ donor, as was the case with her son, the doctor asks the family members if they would like to pray before the operation.

"It was incredibly respectful," she says.

She adds that a prayer was said over her son to make sure everything he was donating was well-received.

Rodriguez says her organization is making sure to respond to concerns.

For instance, people don't have to have the heart symbol put on their driver's license to be a donor. They can sign up online and omit the symbol.

In a way, Valencia's life depends on people becoming better educated about organ donations.

She was diagnosed with diabetes when she was 7, which resulted in a lot of health issues growing up.

In 2012, after also struggling with high blood pressure, she learned her kidneys were failing. Dialysis was her best option while awaiting donor organs.

She had to fight to be on a transplant list. Nevada only has transplants for kidneys, so she is also on transplant lists in Arizona and Utah to receive the organs.

Though she is often in pain, nothing stops her from attending events and talking to people about the importance of organ donations.

"If I can just get one person to sign up, that is a lot," she says.

Despite being tired of the constant struggle that comes with waiting, Valencia has a reason for fighting.

"I'm staring right at him," she says as she tears up looking at her 12-year-old son. "He is what keeps me going."

Contact reporter Michael Lyle at mlyle@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5201. Find him on Twitter: @mjlyle