Holocaust survivor describes life in Nazi concentration camps

When Meta Doran read last year that a rail car of the type used to take prisoners to Nazi concentration camps during World War II was going to be exhibited in Las Vegas, she was moved.

“It was the first time ever that I have seen pictures of that since I was in the United States,” Doran says. “For the first time, it was a true sign of the problems we went through.”

Doran wasn’t able to visit the rail car exhibition, but she didn’t have to. As a teenager, Doran, now 87, survived trips in three such cars while being taken to Nazi concentration camps.

“They packed about 120 of us into those cars,” Doran says. “When they opened it up, 20 or 30 had died, and it was normally (for trips) of two-and-a-half or three days, but that was too bad. They couldn’t care less. They didn’t give us any fresh water, nothing to eat.”

Doran is a charming and opinionated woman who bakes cookies for her visitors, beams with pride when she talks — actually, boasts delightedly — about her children and calls the balance of her well-lived life “fabulous.”

But the disbelief, the pain, the fear and the anger Doran experienced then can be heard in her voice as she struggles to retrieve memories she has spent her life trying to bury.

The death by starvation of her father in the ghetto. The horrors she witnessed daily as a prisoner in Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and Salzwedel concentration camps.

Why does she choose to speak now? “I’m getting older,” Doran says. “I don’t know how much longer I’ve got left, and I don’t want this to be something that isn’t known.

“And, then, my children are entitled to know what the life of their mother was like.”

Doran was born in Hamburg, Germany, into what she describes as a well-to-do family. Her Polish-born father, who had moved to Germany after World War I, worked in the rag trade, collecting rags and old fabrics for wholesalers, becoming “very respected,” she says, and creating a company that became “one of the largest in Germany in that type of business.”

“My childhood was fabulous,” adds Doran, an only child who was raised with an English governess and who spoke English all her life. But by the time she reached adolescence, life for Jews in Germany had become brutally oppressive.

“I mean, the brown uniforms were everywhere,” she says. “I never went to general school. It was always Jewish school. And when we got out, when school was over, we all had an adult waiting for us because, otherwise, we were attacked by teenagers or the Hitler Youth (who would shout), ‘Those goddamned Jews.’ ”

In late 1938 — about six months after the German government had confiscated Doran’s father’s business — Doran’s family was deported to Poland with nothing more than one suitcase each and the clothes they wore.

Why? Officials “didn’t tell us a thing,” Doran says.

They were taken to the train station, and “the train was packed,” she says. “We were taken to the Polish border, then the Poles wouldn’t let us in.”

Luckily, her father’s sister lived in Poland, and they stayed with her for a time. Then, Doran says, “in September of 1939, the war with Poland broke out, and two weeks later they had everything in Poland overrun. We were under German (rule).”

The apartment in which Doran and her family were living became part of a ghetto, a severely overcrowded, bordered and secured area used by the Nazis to confine and segregate Jews.

“We didn’t have to move away, but we had to take other people in with us,” Doran says. It was a “very old section of town. They sealed it. And … no family had more than one room, and our groceries were measured out to us. You couldn’t go to the store and buy more.”

Did Doran, who was then about 13, try to make sense of what was happening around her? “All we tried to do was survive the day,” she says. “We had to worry about having enough so our stomachs wouldn’t be growling and that our food should match the time that was designated.

“People died of pneumonia, of being cold or starving to death. That was Poland in the ghetto.”

Doran was made to work in a tailoring factory while in the ghettos — “What I knew of tailoring you could put into a small thimble,” she says — and, at work, “we would get one plate of watery soup a day, which was more than we had at home.”

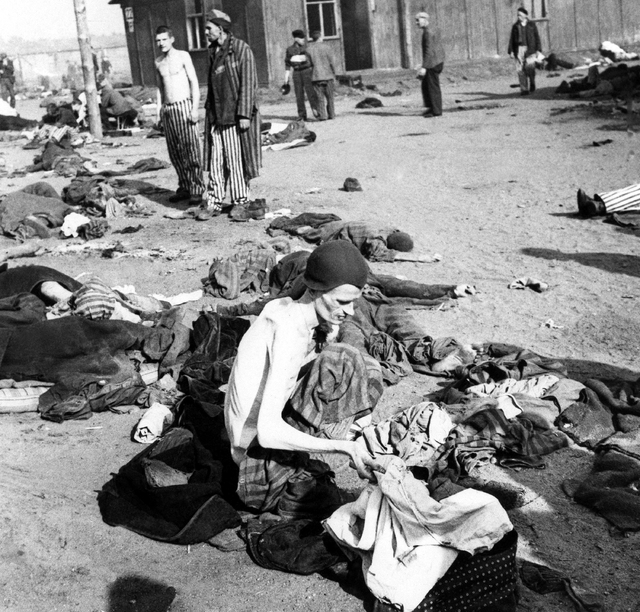

Doran says she and her family lived in two ghettos, and that her father died of starvation during that time. When the Nazis liquidated the ghettos, Doran — who never learned what happened to her mother — was put aboard a rail car and taken to Auschwitz, the concentration camp in German-occupied Poland where an estimated 1.1 million prisoners, almost all of them Jewish, were murdered.

Doran knew nothing of Auschwitz. “All we hoped for was that they should let us live,” Doran says.

Arriving at Auschwitz, prisoners who survived the brutal — and, for many, deadly — trip in the tightly packed, cold rail cars were ordered to walk to either the left or the right.

“I was sent to the right,” Doran says. “I was with the living ones.

“We were sent into a huge building,” Doran says. “The first thing they did to us was shave our heads. No hair. That was No. 1.

“Then, they pushed us into the showers. Now, the other, left side was pushed into rooms that did not have showers but had gas, and they were gassed to death.”

As the surviving prisoners left the showers, they were given shoes and misshapen dresses that did nothing to protect them from the cold. From then on, there would be no more showers, little if any food each day and the constant threat of death.

Doran estimates that she was at Auschwitz for 4½ months before she and other prisoners one day “were picked from the crowd. They took us to the shower house, showered us and gave us fresh wooden shoes and new striped (clothing).”

With Russian troops advancing, the prisoners w ere put into another rail car and taken to Bergen-Belsen in Germany.

Bergen-Belsen “got people in from all over Europe,” Doran says. “Many languages were spoken, and they took the time to have everybody register themselves — where they are from, et cetera.”

Doran spoke not only German, but English, Polish and Yiddish, too, and was ordered to help with the registration of arrivals. That, she says, “saved my life.”

What was daily life like at Bergen-Belsen? Doran rejects the word.

“What are you talking about, ‘life’?” she says. “Existence. There’s no ‘life.’ ”

Meals were “maybe a piece of bread” for breakfast, and lunch was watery soup made out of peelings “from the vegetables the Germans ate for lunch,” she says.

“And people fell around us, dead.”

How did she awaken each morning knowing that she might not live out the day? “You have no choice,” Doran says. “It’s either that or get a bullet.

“We had no choice. That was all that was there for us. Every hour that we survived was found life, because we could have just as easily been killed by somebody.”

Doran doesn’t remember how long she was at Bergen-Belsen, but, she says, “again, the Russians came too close.”

Through her translation and registration duties, “I got to know a few of the Germans that were watching us,” Doran says. One day, one of them approached her “to say, ‘There’s going to be a group of people that are going to be taken out from Bergen-Belsen to be put on a train and sent into Germany to a concentration camp where they work, and it’s fairly decent.’

“He said, ‘I want you to be on that train.’

“He asked me not to open my mouth and tell anybody. He said the reason is that the Russians were coming in close so quickly that the Germans want to kill as many people in Bergen-Belsen as they can and burn them. He said, ‘I don’t want you to be one of them.’ ”

“So I don’t know who this person was,” Doran says, “but I have to give him credit: He saved my life.”

Doran was taken to a camp near Salzwedel in Germany, which, she says, “was better than any of the others.”

The Salzwedel camp was run by an “old-school” German military officer who “had a heart,” Doran says. When the new prisoners arrived, “he put his hand on our head and just enjoyed seeing th at the hair was growing in there. And he brought — I’ll never forget this — small combs.”

Prisoners at Salzwedel worked in factories that manufactured “ammunition of some sort,” Doran says. As prisoners arrived, they were asked if they spoke German.

Whenever such a question is asked, “you never know whether you’ll be shot or they have something for us in mind,” Doran says. “I picked up my hand, and the man who was in charge of the kitchen talked to me, and I guess he liked my answers.”

Doran was assigned to work in the kitchen, making meals for prisoners. “So that was my saving,” she says.

Doran isn’t sure how long she was at Salzwedel. One morning, she says, the prisoners awoke to find that “most of the German personnel had left the camp” and had left the locks on the gate unlocked.

But the camp’s commander stayed, Doran says, and “when the Americans finally came into the camp, they were, first of all, going to shoot him.”

However, she says, the prisoners “told them what he had done for us over the time we were in his camp. So they listened to us and put handcuffs on him and they took him in their jeep. Where they took him, I can’t tell you, but they took him in their jeep, so we saved his life.”

Doran was just 19 years old. What did liberation feel like?

“Relief,” she says. “It was the most wonderful moment of my life. It was freedom, without being concerned about: Are you going to get shot?”

Once again, Doran’s language skills proved to be valuable. She was enlisted as translator and administrative assistant to the camp’s American supervisor, and she and other former prisoners were moved into buildings at a former German military base.

“Do you have any idea what it’s like to see running water? And bathrooms?” Doran says. “All of a sudden, we were beginning to become humans again.”

And eventually, Doran says, “life slowly but surely started again.”

Seeking to find other Jews, she traveled to a zone for displaced prisoners outside of Frankfurt. It was there that she met her first husband, Harry. They were married in a synagogue in Germany and lived in Belgium for four years while awaiting permission to move to the United States.

They arrived in Boston, where Doran had family, then moved to Houston and, in 1954, to Las Vegas. Here, Doran later married her second husband, Gerald, to whom she was married for 38 years, until his death in 2008.

Doran’s home, which is filled with family photos, is a testament to the sweetness of her life after the Holocaust. She counts as her greatest achievement her children: Joseph, a noted implant and cosmetic dentist, Marc, who’s retired from the construction industry, and Paula, who died of cancer at the age of 34 and, according to her wishes, is buried in Israel.

“I have wonderful kids,” Doran says. “I mean, if I didn’t do anything right, by the grace of God I was able, and thank God, to raise them properly. They’re wonderful human beings.”

Doran never talked with her children about her experiences during the Holocaust. “A word here and there, but never in details,” she says.

Why not? “It hurt too much,” she says.

Doran says in telling her story now, “it engulfed me again. It brought back things I haven’t thought of in years.”

The deaths, the hangings, the atrocities she witnessed all “came back to me,” Doran says, “things that I have worked for years and years to put in the back of my mind, because I had to work for the future, not the past.”

Now, she says, “I think it’s time to open my mouth. I don’t know how many years I have left.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.