LEAP OF FAITH

Randy Howard's survival story has been burned into my memory since Nov. 21, 1980.

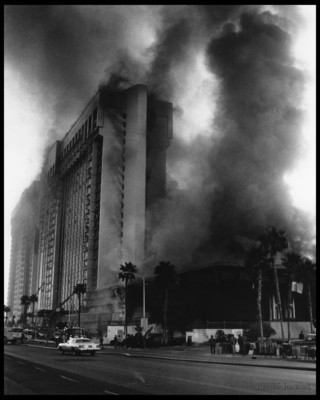

About 7 that morning, Las Vegans awakened to chilling television images of pillars of smoke billowing over the MGM Grand (now Bally's).

Firefighters faced their worst nightmare: hundreds of hotel guests trapped in smoke-filled rooms and hallways. Ladder trucks, their reach limited to lower floors, offered little hope.

Suddenly an alert TV cameraman spotted a cowboy coming down a rope thrown from the roof by a Nellis helicopter crew. Minutes earlier another man had attempted to save himself from the same 14th floor balcony, only to fall to his death in front of horrified onlookers.

The cowboy made it safely to the ground and his remarkable gamble aired on the network news that night, an uplifting symbol amid the tragedy that claimed dozens of lives and injured hundreds.

When it was over, 87 people had died and more than 650 had been injured.

Shaken to the core by cheating death, Howard, 26, headed back to Moline, Ill., just hours after surviving the fire.

I was a San Diego-based Associated Press reporter sent to Las Vegas to help cover the fire. I became fascinated with the cowboy's daring escape and traced him to a flophouse motel next to the Dunes, now the site of Bellagio. I spent so much time waiting in the motel lobby that the receptionist slipped me a phone number that Howard had called in Illinois.

And that's where he was, sleeping at his mother's home in Moline, exhausted from the ordeal. His mother promised to give him my message, and an hour later, he called. The details poured out of him. God had truly saved him that day, he told me.

Every November for almost three decades, I've wondered how he survived the aftermath. Was he still alive? Had his faith wavered? What was his story?

After joining the Review-Journal in 1999, the idea of reconnecting with Howard became something of an obsession. I made numerous attempts to reach him for anniversary stories.

The breakthrough came in May this year. A friend of his sent an e-mail saying Howard was ready to talk. We exchanged e-mails for months and he agreed to e-mail me his story in installments.

As the story unfolded, the MGM cowboy, it turns out, was anything but an average Joe from the Midwest.

TROUBLED PAST

Howard first flew from Moline to Reno on Nov. 19, 1980, his life in shambles.

He had been engaged for more than five years when he became entangled with an old flame. Now he had two girlfriends, one of them pregnant.

"I was so torn I could not breathe," Howard recalled.

He paid cash for a house for his pregnant girlfriend and left town without saying a word.

"I left with the intention of never coming back," he said.

But girlfriends were the least of his problems.

In Howard's suitcase as he flew to Reno were $170,000 in cash and a loaded .357 magnum.

I asked him how he made his money. After a pause, he said: "That's complicated. I was in the import-export business of exotic plants." By his estimation, he made $35,000 to $40,000 a month trafficking in marijuana. He and a partner ran vans from Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Texas north to the Quad Cities on the Iowa-Illinois border, 1,500 to 2,500 pounds a month.

He's not sure why he picked Reno as the first stop, but changed his mind after he got there and booked a flight to Las Vegas.

After arriving about 9 a.m., he asked his cabdriver to recommend a "classy place" to stay. MGM Grand or Caesars Palace, he was told.

He struck out at both. Come back later in the day, they said.

Exhausted from 24 hours of traveling, Howard returned to the MGM Grand and "threw a hissy fit. I remember pulling out a wad of $100s, probably $5,000 worth, and waving it." He soon had a room for three nights.

He headed for Room 1410, which overlooked Flamingo Road, across from the Barbary Coast. The skinny 6-foot-1 ex-Marine spent his first day in Las Vegas catching up on sleep before cleaning up for a night on the town. Over beers in the casino, he heard Ann-Margret was performing at Caesars.

He turned to his wallet again, pulling out $500 at the maitre d' station to get a table "not much bigger than a pancake" and a folding chair in front of center stage.

He ordered the first of what he estimated was more than a dozen beers, offering a $100 tip each time.

When Ann-Margret appeared, she couldn't miss the baby-faced cowboy. During a song, she went up to Howard and with her foot, gently raised the front of his Stetson.

"I felt like a little boy at a circus with a candy store included," recalled Howard, and that was before sharing the spotlight for seconds with Ann-Margret.

The cocktail server had taken notice, too. Near the end of the show, she invited him to a party. Howard, who too often courted danger, was tempted, but his instincts kicked in. "Is this girl liking me," he recalled thinking, "or is somebody out there waiting for me? I was streetwise and a king in my world," said Howard, who drove around the Quad Cities in a blue Cadillac Eldorado convertible. "But I was out of my element."

For once, he decided to play it safe. About 2 or 3 a.m., he headed back to his room, where he remembered sitting down on his bed "still kinda drunk," and "just staring at nothing." It all was sinking in: "the pain, guilt, confusion and out of control life I was living up to this point."

He was sober enough to know that his life had come to a crossroads in Room 1410 as he drifted into sleep. A soul-shaking wake-up call was mere hours away.

DEADLY SMOKE, DARING ESCAPE

The next thing, he recalled, was "slowly waking up to the sound of what I first thought was people fighting and yelling."

People were pounding on his door. There was noise outside his 14th-floor window. Numb from a night of partying, his mind struggled to process the strange sounds.

When he opened his curtains, it was dark out. He opened the balcony door for a better view and thick black smoke "started shooting into my room." It wasn't dark out. That darkness was smoke. The MGM Grand was on fire.

He opened the room door.

As he dressed, other hotel guests rushed into his room. With shock setting in, some ran out onto his balcony, others helped themselves to his bathroom towels and bed linen.

"Now I know they were looking for two things: a way out, and a breath of air."

He joined the others in looking for a way out. For the first time, Howard was gripped by fear.

He heard his inner voice calling out to God "in a more serious, desperate manner."

"I kept roaming the halls in a frantic look for any hope of escape," he said. "I was ready to give up." As breathing became more difficult, he considered jumping. He checked a stairway. Too much smoke. He ran into a room and pushed his mouth against the drain in a wash basin, then bathtub, desperately gulping precious breaths of clean air. He remembered helping a woman do the same.

He pushed on, now in a panic and praying for a miracle. The elevator didn't work.

"There was a moaning that filled the air," he said. "In 'The Ten Commandments' with Charlton Heston, remember the scene where Moses told the Jews to put the blood of a lamb on their door and death would pass them over? That's what it sounded like as everyone waited for death to reach them in the form of fire and smoke."

Smoke was so thick in the halls that he was close to blacking out. Suddenly he tripped over the legs of a woman who was sitting on the floor, with her back against the wall.

Their eyes met. "There was no hope in her eyes."

Howard fell to his knee, folded his hands in prayer and "100 percent let go of my life." He cried out, "Lord in Jesus please get me out of here."

At that moment, Howard looked up and thought he saw something swing past the window in a room.

Leaping to his feet, he looked down at the woman and offered hope. "Don't give up," he told her. "God can save you."

He rushed into the room but there was no rope.

He ran down the hall to the next room. Nothing there. Was his mind playing games? Had he imagined a rope that could bring another form of salvation?

Only one guest room was left in the hall. It was his last chance.

When he entered the room, "there it was." A rope dangled from the hotel roof, a tantalizing gift of life from some Nellis airmen who rushed to the scene in a helicopter.

Several people were gathered on the balcony but no one appeared to be going down the rope.

Howard didn't ask why. He started climbing over the balcony railing when two men grabbed him and yelled, "You can't make it." Then they pointed to the street, where Howard could barely make out the form of a man who had fallen to his death while trying to go down the rope.

Howard wasn't taking no for an answer. Again the men blocked him from trying to go over the rail. He moved to the end of the balcony. When he attempted to reach the rope the first time, it was maybe 5 or 6 feet away from the balcony.

Now it was even farther away, by 2 feet, he estimated. But it didn't matter. Over the railing he went. Focusing everything he had on the rope, he took a leap of faith.

He grasped it with all his might and started his 140-foot descent, using only his arms. He was about 5 feet away from the building, which prevented him from any rest stops. He remembered descending past balconies with people crying for help, their arms outstretched. Shards of glass struck him as panicking hotel guests, desperate for fresh air, hurled furniture through windows.

Not even halfway down, Howard took a direct hit from a large fragment of glass. Luckily, his Stetson absorbed most of the impact. He halted his descent just long enough to push his hat back in place. He has no doubt the hat saved his life when other chunks of glass struck him.

He remembered blacking out at one point during his hellbent rush to safety.

"All of the sudden I was down," he said. With glass still raining nearby, a dazed Howard realized he was standing on the body of the man who didn't make it down the rope.

A firefighter grabbed him and barked, "Next time wrap your legs around the rope."

The next sound Howard heard was wild applause. "People clapping and screaming like (someone had scored) a Super Bowl touchdown. Then someone yelled, 'His hands must be burned up.' "

Howard held his hands up to the crowd. He heard a woman cry: "There's not a mark. It is a miracle."

"Then I heard weeping, the kind of weeping I have only heard at spirit-filled churches, the kind of weeping the elect do in the presence of God. Yes, he (God) stayed with me all the way to the bottom.

"At that moment, I went into shock. I ran through the crowd. I ran as fast as I could. I don't know how long or far. I just remember running into a hotel lobby."

He had entered the Dunes Motel, next to the larger hotel of the same name.

"The clerk was staring at the TV. He looked up at me and said, 'That's you on TV coming down the rope.' "

Howard's face was black from soot. "Every now and then I'd start crying. I was on the verge of a breakdown.

"I don't remember what I said to him," recalled Howard, "but he took me to a room and said, 'You will be safe in here.' He never asked for my name or my money. He helped me in many ways and asked for nothing. I wish so bad I could find this man and thank him."

AFTERMATH

Howard left Las Vegas hours after the fire, with nothing more than the clothes on his back, and two keys to Room 1410.

Upon arriving in Moline the next day, he bought about 20 fire alarms for his family, he said, and a case of Jack Daniels whiskey for himself.

About five days after the fire, he was at his mother's home when a delivery truck pulled up. Howard watched in astonishment -- turning to shock -- as the suitcase he had left in the MGM Grand was returned.

"I was ready to head out the back door. I figured cops were involved," he said.

Still in the suitcase were close to $170,000 in cash, a loaded .357 Magnum, some Thai sticks and several joints.

The MGM Grand also sent him a letter offering a comped room if he decided to visit Las Vegas again.

Five months after the fire, he married Kathleen Ransom. They have two children, including a son who is pursuing a career in criminology. "How's that for ironic?" Howard said.

He got out of the dope business about five years after the MGM fire, but couldn't get the fire out of his system.

"I got a real guilt trip over the ill-gotten gains and gave it away."

He embraced his fame as the MGM cowboy. On one of his favorite cars, he commissioned an artist to paint a mural of the hotel on fire, complete with a cowboy coming down a rope. One of the room keys has been on his key chain for 28 years.

"I struggled at anything that meant being normal. I struggled with authority. I had five businesses but I just kept sabotaging myself."

His gift for gab kept taking him back to his job as a used car salesman.

He recently created a new firestorm with his announcement to run for mayor of Silvis, Ill. The newspaper account, which included his "outlaw" past, elicited more than 200 comments on the paper's Internet site, many of them questioning Howard's religious conversion and his political qualifications.

After avoiding my overtures for years, he came to Las Vegas 12 days ago for closure, he said. (And, yes, the MGM Grand made good on its promise of a comped room.)

But his return to the fire site unleashed some long-buried flashbacks.

A day later, he told me he still was rattled and on the verge of cutting short his stay. "The noises and the smells came back. I'm doing better, but I'm still a work in progress."

Audio slideshow: MGM Fire Survivor Audio: MGM Fire Survivor and Norm Clarke YouTube: NBC Nightly News - MGM Grand fire, Nov 21, 1980