Learning New Tricks

Little Anthony Gourdine doesn't speak with his hands so much as shout with them, his dramatically splayed fingers a never-ending series of exclamation points.

He sits on the very edge of his seat, though sitting's not really his thing: He leaps to his feet every few minutes, he swings his arms wildly like he was being attacked by bats, he acts out his words and twists his features into rubbery masks of exaggerated expressiveness, generally coming off as caffeine personified.

The guy has to be great at charades.

And when Gourdine gets a little agitated, as he is now, he becomes so animated, it's as if he's something that sprang from a cartoonist's pen.

For instance, make the mistake of labeling the celebrated R&B troupe that bears his name, Little Anthony & the Imperials, a doo-wop group, and it's like introducing a lit match to a puddle of kerosene.

"The doo-wop thing, it's a misconception, a total misconception," Gourdine says, his normally soft voice rising to the rafters of his Summerlin home. "Every interview, from here to China, gotta get that straight. When we were 15 and 16 years old, we were kids in the street singing what we called R&B, and then it got the name doo-wop. But then when you get to the kind of material that we got to in the '60s, it's not doo-wop, and I get offended by it. I really do.

"Let me educate you," he continues. "We passed that point. We do not sing doo-wop. We haven't had a doo-wop song since 'Shimmy Shimmy Ko Ko Bop' in 1960. Everything we've done has been R&B. We're not a doo-wop group. I want to get that straight."

Gourdine punctuates his point by clapping his hands together forcefully, but soon he's giggling like a ticklish school kid, peppering his thoughts with lots of laughs.

Gourdine's a good-humored guy. He likes to tell stories and he's good at it, frequently speaking in different voices depending on the tale (one minute he's approximating Redd Foxx's gravelly rumble, the next he's mimicking Anthony Hopkins' English accent).

He's been this way ever since he can remember.

"My mom knew I was different from anybody else in the family, because I would get in the room and play all these different characters, and I'd use different voices," Gourdine recalls with a smile. "She'd say, 'Oh, I hope that boy's OK.' "

Born in New York City in 1941, Gourdine still spends a good portion of the year on the road with the Imperials, who will celebrate their 50th anniversary together next year.

He got his nickname, "Little Anthony," from pioneering DJ Alan Freed, who noted his small size and big voice after Gourdine notched his first hit while he was still a teen in high school, the smash ballad "Tears On My Pillow." In the song, Gourdine's keening, high-pitched voice would make him a young star.

"I had a teenage life from 14 years old to 16, and then I was working," he recalls. "I didn't get to go to prom -- I couldn't, I was on the road. I didn't experience those things, and I miss that. I think about things like that.

"I feel so sorry for young actors and singers and people who started very, very young," he continues, "because I would say that 60 percent of them just hit a wall trying to grow up. You're forcing yourself to become a grown-up in order to fit in, because you're in this in-between world. You're too young to be an adult, and too old to be a teenager. You don't even see life that way."

But with a gospel singer for a mother and a saxophone player for a father, Gourdine was naturally acclimated for a life in show business.

And the Imperials tested their mettle early on by playing the "Chitlin' Circuit," performing in front of tough crowds at black nightclubs and Harlem's storied Apollo Theater.

"I was so scared," Gourdine recalls of playing the venue for the first time, notorious for its hard-to-please audiences. "There were all these little girls there, and when we came out, they were screaming. There were eight or nine acts, and we came on first. We were the only teenage act, these were all old, veteran vaudevillians, and they're giving us the dirty look, 'young punk kids coming in with their little record.' We went out there and killed them little girls. So we thought we were something else."

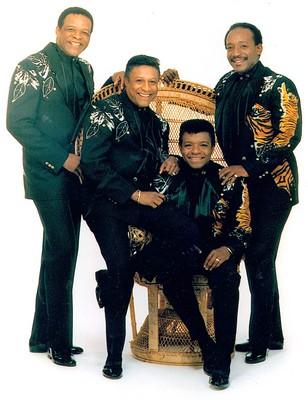

With rich, silken multipart harmonies, a knack for knee-weakening ballads and a knowing pop savvy that manifested itself in everything from chirpy dance tracks to svelte soul, the Imperials notched a slew of hits beginning in the late '50s, climbing high up the charts with such standards as "Goin' Out of My Head," "I'm on the Outside (Looking In)" and "Hurt So Bad."

Along the way, Gourdine also launched an acting career, appearing on TV shows such as "The Jeffersons," landing a role in the movie "Contact 303" with Henry Fonda and starring aside a young Ed Harris in the play "Are You Looking" at the L.A. Actors Theater.

The walls of Gourdine's home double as a scrapbook of sorts for his long career.

His office is lined with photos of him with the likes of Ruth Brown, Boyz II Men and Michael Bolton, in addition to acting honors such as the Los Angeles Dramatic Arts Awards and the Dramalogue Critics Award. Next to the TV in his living room is a large framed poster for the Long Island Music Hall of Fame, which the Imperials were inducted into last year, joining the likes of Tony Bennett, Billy Joel and Barbra Streisand.

"I'm really proud of that one," Gourdine says as he takes the poster in.

The Imperials disbanded for a time in the '80s, but reunited in front of a crowd of 14,000 at Madison Square Garden in 1992, where they were backed by Bruce Springsteen's E. Street Band. After performing as part of the 40th anniversary show for Dick Clark's "American Bandstand," they decided to get back together permanently.

"We kept getting together for things until we just looked at each other and said, 'This is silly, man, we might as well just stay,' " Gourdine says.

And while the group continues to perform regularly, with a Las Vegas show scheduled for Aug. 4 at The Club at The Cannery, Gourdine is wary of nostalgia trips. He considers the Imperials to be a contemporary pop R&B outfit, and takes pains to distinguish his group from acts that do little more than relive the past. "It's the saddest thing in the world to see a bunch of these older artists and they're trying to sing the same tunes for 60 years," Gourdine says. "You can't stay there. Don't you want to spread out? Don't you want to try anything different?"

To this end, Gourdine tries to keep pushing himself in fresh directions, recently completing a new album.

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon, he has just finished listening to some Donald Washington, and he seems inspired, smiling wide, looking like a little kid still harboring plenty of big dreams.

"I'm still learning," he says. "Maybe that's why we've lasted 50 years. The worst thing a person can do, as an artist, is to have other people define who you are. You've got to stick to who you are and believe in what you do," he says, before getting one last zinger in with a wink. "If we were a doo-wop group, we wouldn't have survived this long."