No Español es un problema

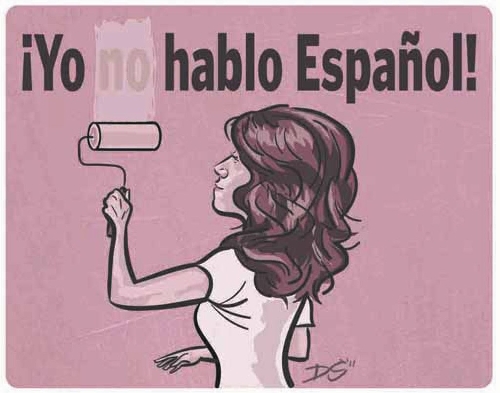

Yo no hablo Español.

When your average gringo says those words, it simply translates to "I don't speak Spanish." When a Mexican-American says them, it translates to many things. Mostly judgment.

Judgment from servers at Latin restaurants, judgment from people whose hands I'm in the middle of shaking, judgment from my own extended familia. They all want to know why I don't speak Spanish and they all think I owe them an answer.

"It's none of your business," is usually my instinct. "It's a long story," is usually my reply.

Both my parents learned to speak Spanish first and English second. My mom in Texas, my dad in Mexico.

When my dad legally moved to this country at age 10, he didn't speak a lick of Ingles. His linguistic challenge became his American classmates' punch line. He pushed himself hard to learn the language, but even after he got the hang of it, his accent betrayed his ambition. And, I don't need to tell you what happened when the new Mexican kid mispronounced a common word in a room full of fifth-graders. Needless to say, every time he had to speak up in his new language, he'd freeze, get self-conscious and want to be anywhere but there.

Fast forward 14 years and he and my mom both speak primarily English but they plan to raise their son speaking both languages. And that's what they did. My brother, the oldest of us four kids, was bilingual. Until kindergarten started.

He had trouble separating the two languages with his teacher and peers. It was causing a distraction, both for my brother and his fellow students. As soon as my dad got word of this, it was all English all the time with his son.

That's why my brother doesn't speak Spanish and that's why his three sisters don't, either.

People are quick to judge my parents for biting their native tongue with their children. They see it as deprivation, be it of career opportunities or cultural enrichment. In reality, my parents were doing what good parents do best. They weren't trying to deprive us of anything. They were trying to protect us.

See? Long story. Well, too long to share with the nice lady at the burrito drive-thru I frequent. Yes, she's asked. That's what happens when you can pronounce beautiful Spanish words the way they were meant to be pronounced. With the rolling r's, loose l's and pitch-perfect accents. When you say those words from behind dark hair, dark eyes and, at least three months out of the year, dark skin, the confusion is compounded.

People make assumptions. When you don't validate their assumptions, they get disappointed. Sometimes even disgusted.

Six years ago, I went to a local Mexican market to buy all the ingredients necessary for a meal I planned to prepare for my dad: chicken mole con fideo y homemade flour tortillas on the side. I asked a staff member for help finding the fideo and he replied in Spanish. His tone was friendly and helpful. Until I pulled out that handy "Yo no hablo Español" phrase.

He looked me up and down, the way a Latino father looks at his daughter -- when she's three hours late for curfew. "Why not?" he demanded, the friendly, helpful tone nowhere to be found.

I actually knew how to ask for fideo in Spanish. I also knew how to call him every cuatro-letter word the Spanish language offers. I refrained from the former because I knew I wouldn't understand his answer. I still don't know why I refrained from the latter.

Probably the same reason I let it slide when my aunts teasingly call me a "gabacha," slang for white girl. They just don't get it.

They think I've turned my nose up at the language. They see it as a rejection of myself, of them, of the culture as a whole. As if I enjoyed speaking to my paternal grandma -- 'Buelita' -- with an interpreter. As if I could possibly watch my mom labor over tamales, hear my dad's thick accent as he recalls his days in Mexico, appreciate an old Pedro Infante song, or take in a Frida Kahlo painting without feeling a deep connection with my culture. You don't need to speak the language to be proud of your heritage.

That said, I want more than anything to speak the language. My Spanish tutor, Cristina Rodriguez, says I'm an advanced pupil. When it's just me and her, conjugating verbs in a back corner of Dead Poet Bookstore, I agree. When it's time to take those skills into the real world, I feel like the fifth-grade version of my dad. I freeze, get self-conscious and want to be anywhere but there.

It goes back to those assumptions, but it's about pressure, too. I'm not exactly the retired guy brushing up on Spanish for that upcoming cruise to Costa Rica. I'm a Mexican-American who wants to speak to her parents in their native tongue.

I can't wait to erase the "no" from "Yo no hablo Español" and I can't wait to never tell that long story again.

Contact columnist Xazmin Garza at xgarza@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0477. Follow her on Twitter at @startswithanx.