The Doctor Is In

A lot of kids cry in the doctor's office, especially when he's poking around, tapping them with strange instruments and asking weird questions, such as "Who's the president?"

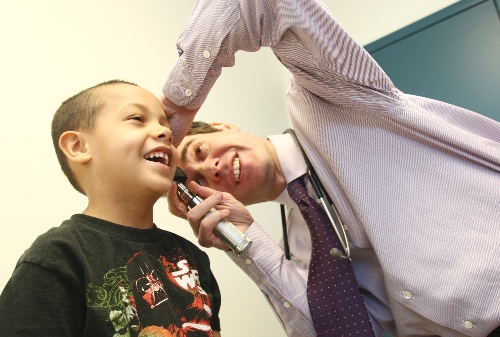

Ishaiah Fedor, 5, giggles. And when he's not laughing, his mouth is set in a happy grin. His parents, however, are not smiling. They wear concerned expressions, mother Brianna Hooks anxiously looking over the doctor's shoulder as he diagnoses Ishaiah with rubber duckies in the nose.

That's not the real problem, obviously; looking in a kid's nose and telling him it's filled with yellow squeaky toys is part of pediatrician Noah Kohn's schtick. And it lightens the mood in the exam room.

Hooks and her husband, Luke Fedor, brought Ishaiah to see Kohn at Cunningham Elementary School's health clinic on a recent Wednesday after the boy's kindergarten teacher noticed a significant change in his handwriting.

Ishaiah had spent the entire spring break week fighting an illness that made him stagger as though he was drunk. He was listless, tired and sullen compared to his normally sunny disposition. It scared Hooks and Fedor, but the family has no health insurance; Fedor's work policy won't kick in until he has been on the job as a pre-loader for UPS for 16 months. Their only option was to wait it out.

Enter Kohn. Were it not for the free health clinic Kohn operates, Ishaiah would not have seen a doctor until his condition became severe, Hooks says.

A board-certified pediatrician and 1995 graduate of Georgetown medical school, Kohn, 41, quit a successful private practice in Summerlin to be the sole medical provider for Clinics in Schools, a nonprofit organization that provides school-based health care to local children. It provides free primary care medical services on a shoestring budget of $240,000 a year. While the Clark County School District is a partner with the organization and the clinics are on school grounds, Clinics in Schools does not receive state funding, Kohn says. Instead, the program is funded by organizations such as United Way and personal donations.

It may seem odd that a Georgetown graduate left a busy medical practice to work for an upstart free clinic. But Kohn -- who grew up poor in the hills of Vermont, the son of Dutch and Hungarian immigrant parents -- says he felt like he wasn't giving back to the community in a meaningful way.

The clinics were started as a program by Communities in Schools, a local chapter of a national nonprofit that works to reduce school dropout rates. The first health center opened at Martinez Elementary School in 2004 with the Cunningham location following in 2008. Since Kohn took over as the sole medical provider about two years ago, he has treated thousands of children who otherwise wouldn't receive health care, he says. A third clinic is planned for the campus of Elaine Wynn Elementary.

Ailments range from twisted ankles, sore throats, bed bug bites and well child checkups to more complex cases, such as Ishaiah's. A recent patient was diagnosed with severe anemia due to internal bleeding, Kohn says. Children like that are referred immediately to an emergency room.

The majority of his patients come from families who are classified as below the poverty line. The average family that walks through the clinics' doors makes $13,000 a year and supports 4.6 people. Last year, Kohn provided care during 6,294 visits at both clinics combined. A dental hygienist also provides cleanings and other dental services, while University of Nevada, Las Vegas counseling interns provide mental health care.

Kohn splits his time between both sites, spending 2½ days a week at each location. Such a service is needed, Kohn says, because more than 18 percent of kids starting kindergarten in Nevada have no health insurance.

"That's staggering," Kohn says. "They have nowhere else to go."

The program has made a positive impact on the school, says Cunningham principal Stacey Scott-Cherry.

It helps parents who may not have the transportation to a doctor and provides them with a convenient location to get their children vaccinated. Also, kids don't have to miss an entire day of school to go to the doctor or dentist.

Kids in good health tend to be more alert in class, better behaved and more engaged, she adds.

"I would say by having these needs met absenteeism has decreased," Scott-Cherry says.

There are other low-cost clinics in town, but they operate on a sliding scale fee basis. Even if they charge $10 for a doctor's visit, that might be more than parents can afford, Kohn says.

Fedor and Hooks are a prime example of such a family. They moved here a year ago from New Mexico after Fedor transferred to get more work hours. When they arrived in Las Vegas, he was laid off from UPS. Now he is working only about 20 hours a week, and insurance won't kick in for the family until next year. Hooks can't find work. They also haven't been able to qualify for Medicaid.

"What do you do when you can't get insurance?" Fedor asks. "What do you do if you don't have the money to go to the doctor? This clinic means a lot to us."

Their options were to take Ishaiah to the emergency room or hope and pray he got better. When the boy's condition improved, they thought their prayers had been answered, until his teacher pointed out how messy Ishaiah's handwriting and drawing had become.

Kohn examines the boy, asks him to touch his nose and fingers then walk across the floor. After several minutes, he turns to the parents.

"I'm inclined to think he had strep," Kohn says.

Still, he needs blood tests and to see a neurologist, just to be safe. Kohn thinks he can get them an appointment in a few days and calls a local pediatric neurologist. Both doctors agree about the strep infection theory, but the neurologist also worries that Ishaiah has a viral infection and inflammation of the cerebellum. He suggests an immediate emergency room visit.

The family stands to leave, the decision of whether to take Ishaiah to University Medical Center or Sunrise hospital to be decided in the car.

"That's the frustrating thing," Kohn says after they leave. "I know everything we do here we can do for free. Now the burden falls on UMC. They will send them a bill. It's going to be a big bill."

One they likely can't pay.

Contact reporter Sonya Padgett at spadgett@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564.