CCSD’s failed desegregation history remains visible today

“Old Man Segregation is on his death bed,” the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said in a speech in Las Vegas on April 26, 1964. “The only thing I’m concerned with is how costly the segregationists are going to make the funeral.”

While segregation had already been struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court 10 years before King’s speech, its legacy remains visible to this day in the Clark County School District.

On a recent day at Booker Elementary School in west Las Vegas, Assistant Principal LaDonna Henderson sported a pink shirt underneath her blazer that read “Pretty Brown Girl” — the name of an after-school program that aims to boost the self-esteem of girls of color and instill good values.

The program is one of the bright spots at Booker, which struggles to provide its students with a quality education.

The district has been trying to desegregate and lift up Booker and other schools in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside and southern North Las Vegas for more than 45 years.

The first effort, which began in 1972, involved the creation of schools known as Sixth Grade Centers and required massive busing of students into and out of the Westside. The centers were discontinued in 1993, when the district abandoned busing and refocused its desegregation efforts on providing quality educational options in the area through the Prime 6 initiative.

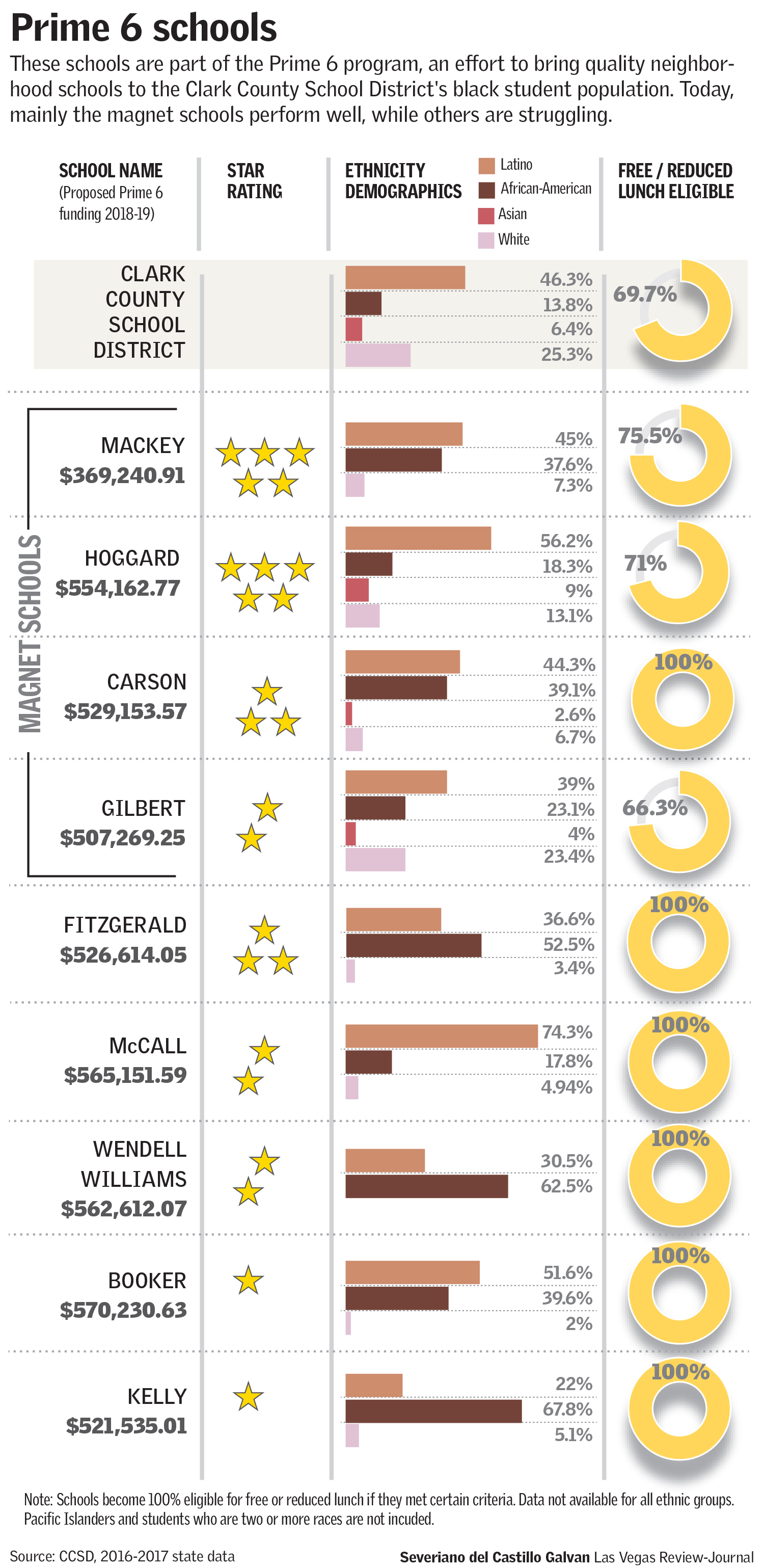

Prime 6 schools receive extra funding, community facilitators, security monitors, learning strategists and other positions to help boost achievement. Five of them also receive state Victory dollars reserved for high-poverty schools.

An uphill fight

Yet today, many of the nine Prime 6 schools — including Booker — are still in an uphill fight.

Five of the schools received one or two stars in the state’s five-star accountability rating system. They also serve some of the district’s poorest families, with the percentage of students eligible for free or subsidized lunches higher than the districtwide average in nearly all cases.

The district’s chief academic officer, Mike Barton, said that parts of the Prime 6 program have been successful — particularly in three magnet schools and at Fitzgerald Elementary, which improved to a three-star rating this year — but acknowledges that more work needs to be done.

“Historically, this is an area that has been underserved and under-resourced,” he said. “We’ve got to continue to look at what’s working.”

Some of the challenges may derive from the de facto segregation that persists in the area, albeit with new ethnic underpinnings.

All of the schools have higher percentages of black students than the district average.

And although there are plenty of other schools in the Westside and North Las Vegas, state data still show an overall achievement gap between the performance of black students and other groups.

Black students in grades three through eight were the lowest performing subgroup in the district in math and reading proficiency, according to state data for 2016-17. They also had the lowest graduation rate.

Meanwhile, the percentage of Hispanic students has been growing in the schools, including many immigrants who require additional language instruction.

A 2009 study from the UCLA Civil Rights Project forecast this trend, warning that the Prime 6 schools could face “triple segregation” based on poverty, ethnicity and linguistic differences due to the growing Latino population.

Failed busing scheme

The Prime 6 plan emerged after two decades of the Sixth Grade Centers.

That plan bused all sixth-graders into west Las Vegas schools like Booker for sixth grade only. But it bused black students out of their neighborhoods for 11 of the 12 required years of education.

“It was crazy with the Sixth Grade Centers,” said Marzette Lewis, a community activist who lobbied the school district to end the program. “Nobody wanted that.”

Prime 6, which began in the 1993-1994 school year, finally allowed students in the Westside and North Las Vegas to stay in their neighborhood school if they wanted.

While students were — and still are — technically assigned to schools outside the area, they can enroll in Booker, Fitzgerald, McCall, Kelly and Wendell Williams elementaries, depending on where they live. Carson, Mackey, Gilbert and Hoggard Elementary schools are magnet schools with an acceptance based on lottery.

All schools also have an additional 19 minutes per day, and offer kindergarten and pre-kindergarten for neighborhood children.

“The whole concept of moving to the Prime 6 was to allow students to come back to their neighborhood schools, to give those schools an opportunity to still be quality schools with quality educational programs,” said Trustee Linda Young, who was the principal at Mackey Elementary while it operated as a Sixth Grade Center.

Success not equal

But quality is not universal in the targeted schools.

The schools that were converted into magnet schools are generally seeing greater academic achievement — Hoggard Elementary and Mackey Elementary are five-star schools, while Carson Elementary earned three stars.

That speaks to the strengths of the district’s award-winning magnet program, although not all students who want a seat can get one.

Fitzgerald Elementary, which is not a magnet school, is a recent success story, as the school just pulled itself out of the district’s Turnaround Zone and reached three stars.

While the extra money helps, former principals say people are crucial if the schools are to succeed.

Young, who now represents the Westside, said the biggest challenge is attracting quality teachers in a tough environment.

“Teachers are really concerned about being labeled as a ‘poor teacher,’ when many of the factors that determine the stability of the home or the community they have no control over,” she said. “And that makes a big difference in academic achievement for students.”

Beverly Mathis, a principal at Booker from 1994 to 2011, said success depends on leadership. But she also noted that she was blessed during her time there because of staff stability.

“We kept the same staff and it made all the difference in the world,” she said. “Because of the consistency.”

Other solutions

Yvette Williams, founder and chair of the Clark County Black Caucus, believes there are a number of reasons black students are still underserved. One problem, she argued, is that they are underrepresented in magnet schools.

“I would go as far as to say a large reason why black kids are underrepresented is not because they’re not applying,” she said. “There are sufficient students applying to properly represent black kids, but they’re not being accepted.”

Admission to magnets and career-technical schools are based on a lottery system that considers a student’s proximity to the school, but also gives preference to those who have siblings in the school or are coming from another magnet program.

Gia Moore, director of the magnet school program, said the district has been working with the caucus to address the concerns.

She noted that some African-American students and parents have been concerned that career-technical academies are not the best choices for them due to the lack of athletics or other extracurricular activities.

Prime 6 legacy

District officials acknowledge there is still work to be done.

Barton, the chief academic officer, said the district will continue to examine the resources that work well and replicate those successes elsewhere.

The district’s Prime 6 plan, he said, has worked in pockets — but not across the board.

“We don’t have all these schools up to where they need to be academically,” he said. “But it’s a heavy lift every time there are those at-risk obstacles weighing heavily on students.”

Meanwhile, at Booker, the administration is figuring out how to help its lowest-achieving group of students: African-American boys.

“We’re looking at what kind of things can we put in place to push that group to understand education’s important,” said Henderson, the assistant principal. “That coming to school is important, that what you do on a test is important.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.