Clark County’s recovery high school helps at-risk pupils

Khara Greenwell knows from her drug treatment program that there are three mainstays in the lives of those dealing with addiction: jails, institutions and death.

At 16, she’s seen two of the three.

“I knew death was next,” she said of her decision to shake her addiction to mind-altering substances and earn a high school diploma at the same time.

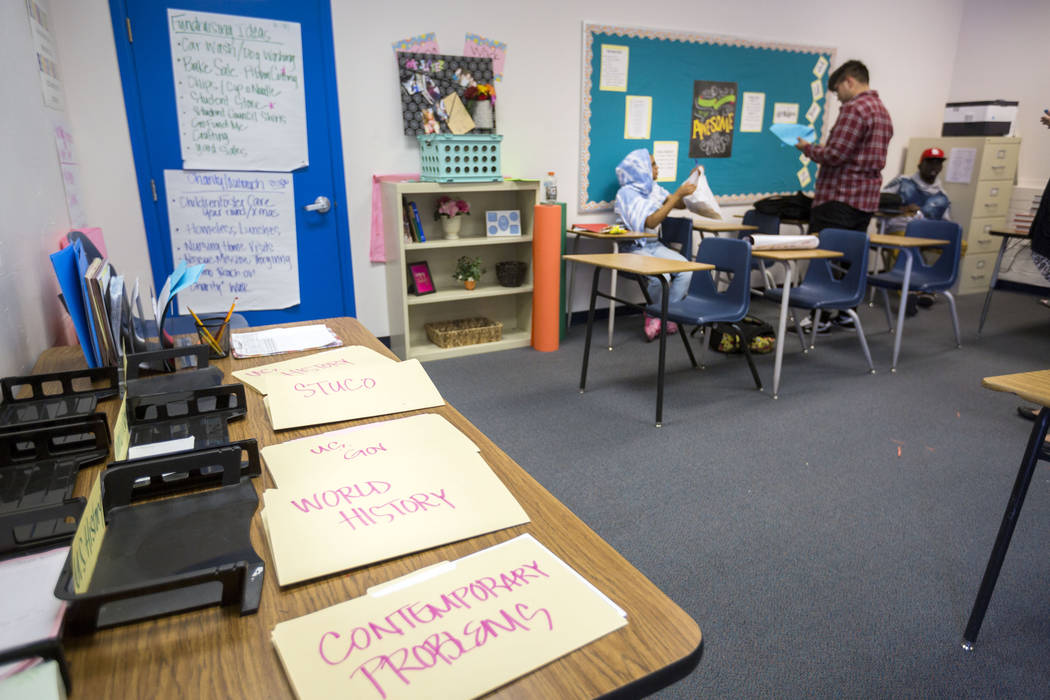

Khara is one of 21 students fighting for their futures at Mission High School, the Clark County School District’s new program for students struggling with addiction. The school opened Aug. 21 — a week after the start of the traditional school year — with six students, Principal Barbara Collins said, but it has grown rapidly since then as a result of referrals from other schools and the juvenile justice system.

The so-called recovery high school, on the site of the former Biltmore Continuation High School, is a first for Clark County. But it’s part of a national movement that began in the mid-1980s and has accelerated amid soaring overdose deaths associated with the opioid epidemic.

Clark County’s experiment has a relatively new wrinkle: Research shows most recovery programs are operated as small units within a traditional high school, rather than as a stand-alone school like Mission.

Khara’s story is similar in many respects to those of her fellow students, whose addictions include alcohol and drugs ranging from marijuana to heroin.

She said she was 12 when she was introduced to illegal substances by her mother. She eventually stopped going to school and instead spent time in juvenile detention and two rehab facilities. Now, though she’s old enough to be a junior, she’s attending high school for the first time.

“This is my second shot,” she said Thursday in the schoolyard.

Like a mom

Last year, Collins was the principal at College of Southern Nevada High School, where 100 percent of the students graduated and 35 earned an associate degree before they collected their high school diplomas.

She admits Mission High School is a little bit different.

Most of Collins’ career has been spent working with at-risk students, though, and she said her faith was part of the decision-making process to take the Mission job.

She compares her job to that of a physical therapist after a person is in a serious car accident. Sometimes people have to learn to walk again or talk again.

“That’s what we’re doing here but with attitude and learning how to live without self-medication,” she said.

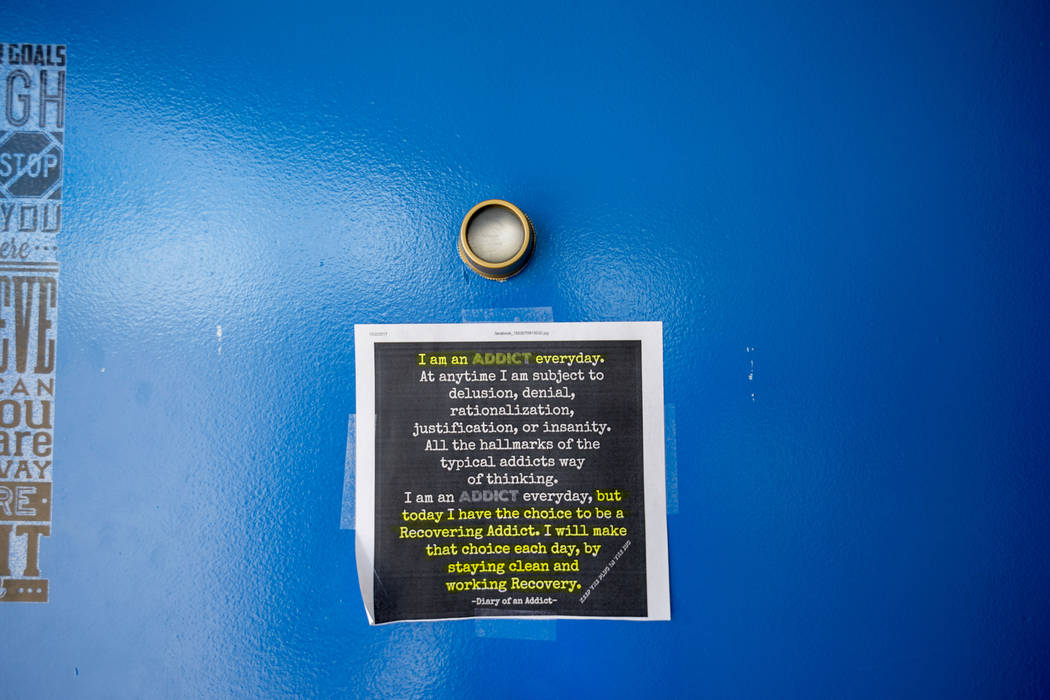

She tends to function more like a mom than a principal to the students, who have to abide by three tenets when they enroll:

■ They must attend a peer-supported recovery group.

■ Their parents and guardians must commit to some type of family counseling or support.

■ They must consent to random drug tests.

A failed drug test doesn’t necessarily result in a student being booted from the school. Instead, the tests offer a chance to beef up support and intervention, Collins said.

“They’re not bad kids acting out,” she said. “They’re sick kids trying to get better.”

Building a program

Rows of dog tags hang in Collins’ office, the school’s version of sobriety chips. There’s one for newcomers and different tags to celebrate sobriety milestones: 30 days, 60 days, 90 days and a year.

The tags are all engraved with the name Mission High School. Because these are teens, Collins put a hashtag on each one.

Collins expects enrollment at the new school to grow as word spreads, and she believes it might eventually reach the 100-student limit set by the district. But she knows there are even more students with substance-abuse problems.

From 2005-2010, an average of 9.9 percent of people 12 or older in Clark County had a substance use disorder in the past year, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Collins cites that number frequently.

On Monday the school will officially open to the public with a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Collins said she expects more than 250 people to be on hand at the campus on North Veterans Memorial Drive.

“I have more support at this school than if I took all my (previous) 20 years combined,” she said.

Along with the backing of the district,

The state Department of Health and Human Services is contributing roughly $150,000 to fund three full-time counselors. Caesars Entertainment Corp. chipped in $5,000, and the city of Las Vegas will spend $100,000 to make the campus a more welcoming space.

A place of peace

For 17-year-old Laura Johnson, who said she abused drugs for seven years, the school already is a place of peace where she can get away from the stresses that helped trigger her use. A shaded area in the back of the school lot includes picnic tables for students to eat lunch.

“Obviously, it’s hard to come off drugs,” she said. “Sometimes it’s overwhelming with how much support you have here.”

Like Khara, Laura is way behind in school.

Because of her addiction, Laura didn’t attend high school very often. Before enrolling at Mission, she said, she was just working and making money to provide for her habit.

Johnson and her boyfriend, 19-year-old Dylan Bronder, have both been clean for about 60 days.

She said they both struggle at times. “There’s good days and bad days,” she said.

But the regular routine of attending school, working toward educational and lifestyle goals and making new friends helps them cope, she said, noting they were recently elected homecoming king and queen.

That was a good day.

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.