Global Community High School’s future uncertain amid changes

Jose Ivan Cervantes arrived in Las Vegas as a high school freshman, awestruck to be in “one of the most important cities in the U.S.,” and speaking almost no English.

But after enrolling at Global Community High School, a school for new immigrants, Cervantes said he flourished, becoming student council president, a tutor to his peers and a member of the school organizational team.

Now poised to graduate, he’s also advocating for his school, which has faced uncertainty as the Clark County School District considers changes to how English learner students are taught.

“It’s nice to have people you can relate to, especially when you’re missing your family and friends,” Cervantes said of Global. “I want more students to have that.”

‘No answers for years’

The door that opened for Cervantes at Global was about to slam shut after the district proposed eliminating grades 9 and 10 from the school on May 12. Though the plan was scrapped after public outcry, it opened old wounds for the school’s advocates, who say they’ve struggled to get clear answers on Global’s future.

In 2019, they turned out in opposition to a proposal to have the school share its new campus, at Maryland Parkway and Oakey Boulevard, with a workforce development program, which was granted 600 seats to Global’s 400. The school ultimately was co-located with program, with the campus set to open next year.

But questions still remain about who will lead the new facility and how much access Global students will have to the career programs. The school had also been waiting to hear about possible changes to its curriculum when the surprise announcement came that two grades would be dropped.

Social studies teacher Machelle Rasmussen said the school is open to change but wants clear communication and a say in its future.

“We had no answers for years, and now it’s a time crunch,” Rasmussen said. “If you want changes, you need to do it correctly.”

Global teachers also have their own improvement ideas, Rasmussen said, such as adding busing and offering more than the existing 200 seats to serve additional newcomers. At the state level, standards are needed for an intensive English language course for older students, she said.

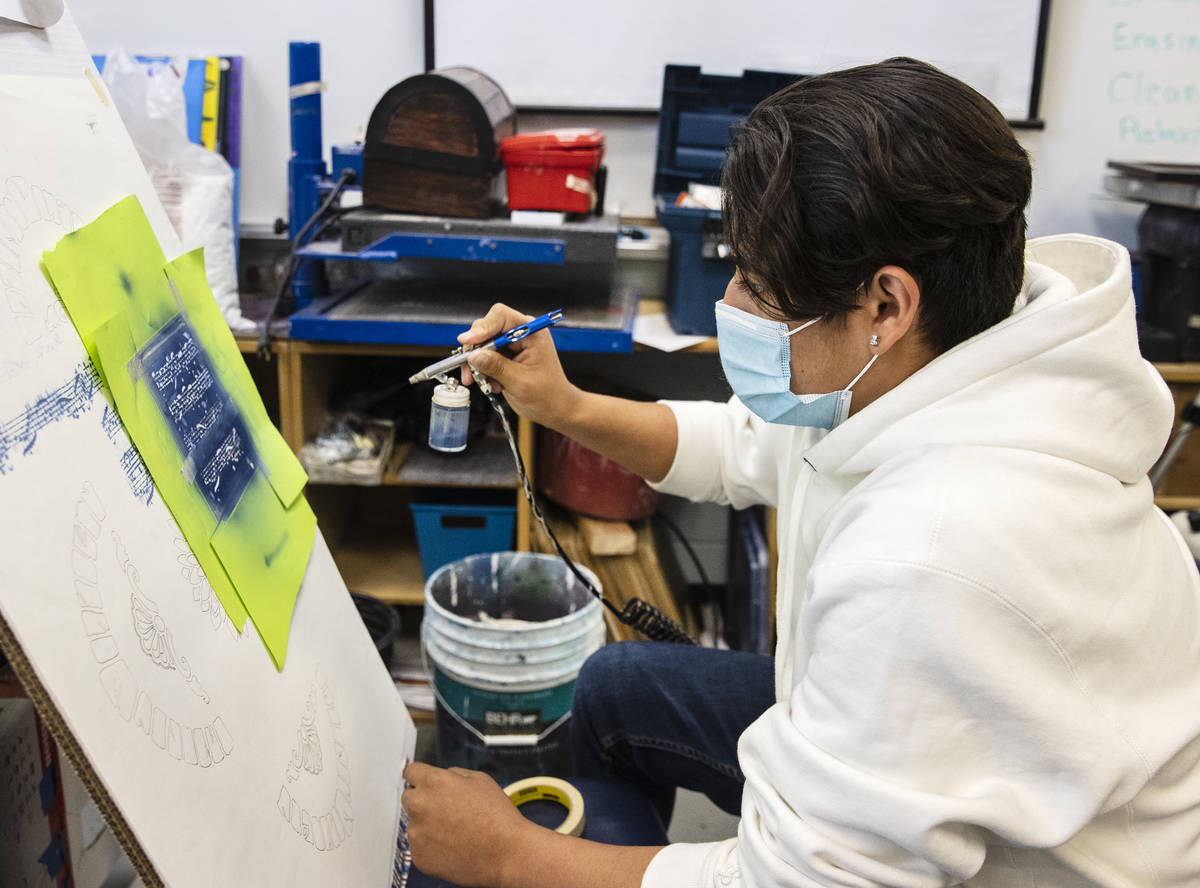

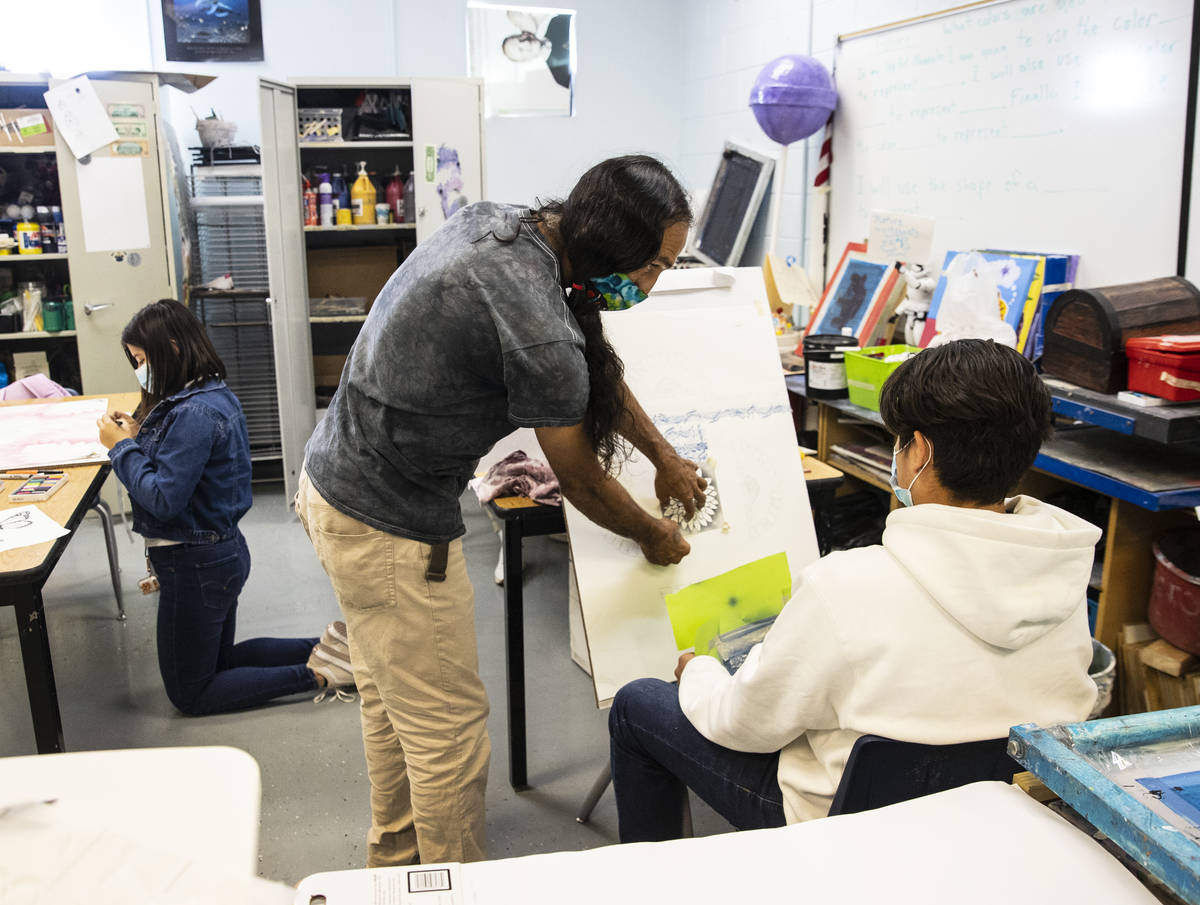

All Global classes are taught in English, but teachers employ a variety of strategies to help students, Rasmussen said, like defining relevant vocabulary before a lesson or explaining cultural and historical references. Most teachers speak multiple languages, and students also frequently help each other with English, she added.

“There’s so much assumed knowledge,” Rasmussen said of traditional lessons. “You need to be able to pause and ask if they understand, and they need to feel comfortable enough to say no.”

The district did not reply by deadline to interview requests about Global, and it’s not clear what fueled the short-lived proposal to turn the school into a two-year program. School staff heard Thursday that Global will be tasked with developing a program for students who have demonstrated enough proficiency to transition to a traditional high school.

Return of bilingual education

The school’s advocates say they’ve heard concerns from district leadership that the school’s instructional model isn’t optimal, long term, for English learners, who benefit from bilingual instruction.

While the district had bilingual classes at several schools a decade ago, there are no such formal programs now, due in part to staffing issues.

But work is underway to bring those programs back.

Vanessa Mari, a Nevada State College professor of teaching English as a second language, said a district committee is creating plans for schools that are interested in the programs.

One common setup sees both English learner and monolingual English students in a class together, taking half the day in English and half in another language.

Research shows both groups of students outperform students in English-only classes in all areas, Mari said, as students learn and test in multiple languages. The programs have been linked to higher achievement, lower dropout rates and an earlier exit from English learner status.

“The student is able to grow both languages, allowing English learners and newcomers to keep both languages,” Mari said. “Right now, English learners come into the U.S., and by the second generation, they’ve lost their first language.”

But the shift doesn’t have to leave Global behind, according to Mari, and could instead standardize what’s already taking place at the school.

“I think there’s definitely a chance for Global to do this,” Mari said. “In speaking to teachers, they are already doing many of these practices.”

Teacher shortage

One of the main roadblocks to offering the programs is hiring enough bilingual teachers, according to Mari. But it’s tough to entice teachers to spend additional money for another certification if there aren’t relevant jobs awaiting them.

Nevada State College’s is one of just two programs statewide to offer coursework leading to a bilingual certification, according to a recent policy paper on the viability of bilingual programs in Nevada.

The paper, co-authored by UNLV’s Alain Bengochea and Elizabeth Greer, noted that the number of emergent bilingual students has increased in Nevada by 60 percent over the last decade, representing around 20 percent of the school population in the state.

Around 15 percent of these students demonstrated proficiency in math and English, according to the paper, while the general student population scored at 42 percent and 55 percent proficiency, respectively.

District data also showed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a dual impact on English learners, over half of whom received failing grades during the first semester of the 2020-21 school year, but who also voiced hesitation to return to school buildings in a January survey.

The policy paper encourages the state to ensure equitable access to bilingual programs, to implement a curriculum that equally uses English and another language and to allow flexible staffing as districts develop their corps of bilingual teachers.

Mari said the district’s bilingual initiative could roll out with one program at each school level to start, though the hope would be to eventually have as many programs as possible.

“In my vision, the more the better,” Mari said.

More than language

Beyond language instruction, Global’s advocates say that the school provides social-emotional support for new immigrants, who may have suffered trauma in their home countries or en route to the United States.

“Global provides one of those rare spaces for our immigrant students to feel safe almost immediately,” said Silvina Jover, a teacher at neighboring Desert Pines High School, speaking at Global’s school organizational team meeting.

“School is more than academics, and Global helps students navigate their (social-emotional) challenges — something that’s difficult to do in a school with 3,000 students.”

Students also say the smaller, close-knit environment makes them feel more comfortable asking for help. At their larger home schools, they described feeling lost, or even being turned away due to disruptions in their schooling that have left them without enough credits to graduate.

Sophomore Estefany Flores said she felt like she wasn’t capable of taking higher-level and Advanced Placement classes at her home school.

“I was so scared, and I felt like they didn’t understand me at all,” Flores said.

But Global offered a more welcoming atmosphere, Flores said, with a diverse student body, small classes and a kind staff, making the prospect of advanced classes much less daunting.

“Any teacher will step in and help you if they can,” Flores said.

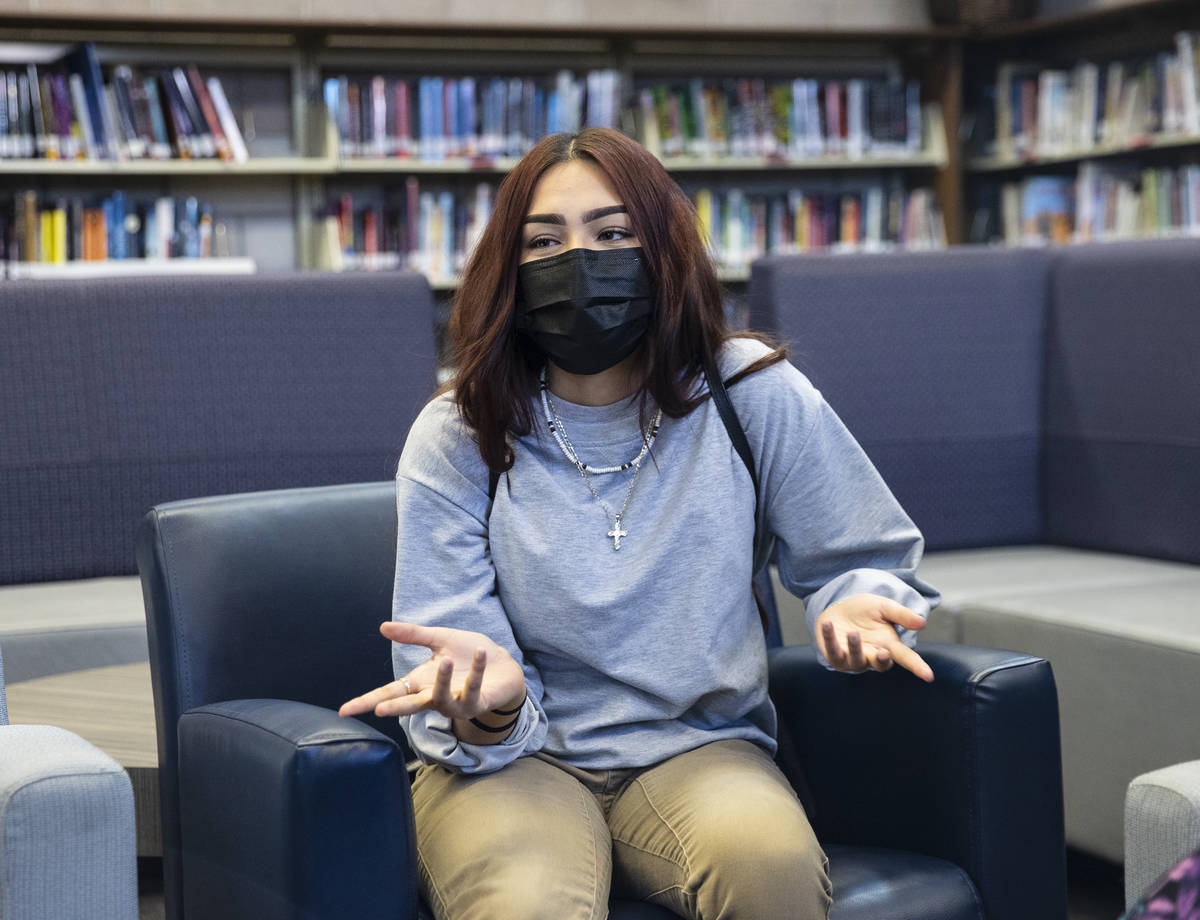

Senior Rosse Ayleen Berrones attended Global during her freshman year, but then spent two subsequent years at other district and private schools in Clark County — a period of time she said left her in tears every day.

“I wasn’t that good at English, and I felt taken advantage of. I didn’t make friends. Nobody talked to me,” Berrones said. “Teachers would say things like, “I already explained it to you.”

She returned to Global as a senior and two years’ worth of credits short of graduating, and begged the school to help her catch up. Another benefit to the school is its experience collaborating with the Adult Education department, Rasmussen added.

“Rosse put in the work,” Rasmussen said of her student, who’s now on track to graduate after attending classes every day from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.

The school has been more than an academic lifeline, Berrones said, offering stability amid personal upheaval.

“The only thing that’s keeping me happy is Global.”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.