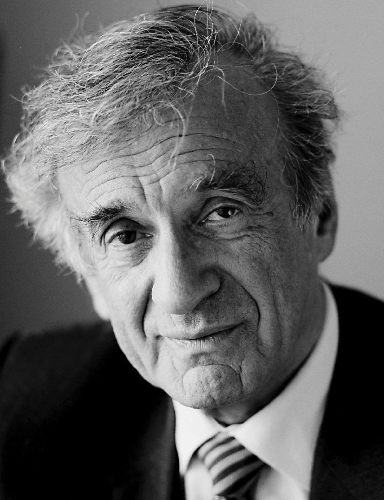

Holocaust survivor recalls monstrosity past but keeps hope

Elie Wiesel answers the phone for an interview and, before the first question can be asked, offers one of his own.

Your newspaper, he asks. Is it a daily newspaper?

Yes, it is.

"I used to be a journalist for 25 years," Wiesel explains with a chuckle, and, even today, he feels "empathy" with journalists.

"I'm sad," Wiesel adds, "that the printed press is going through such crisis."

Only after the interview has ended does the thought occur that the exchange shouldn't have been surprising. Wiesel's gracious attempt to learn about a stranger before talking about himself lies at the heart of what he has spent his life doing: seeking to understand people, both individually and collectively, and, for good or bad, what they do.

Wiesel is a Holocaust survivor and the author of more than 50 books, including "Night," a deeply moving memoir of his own Holocaust experience that has become a key volume in the canon of Holocaust literature. He's also a college professor, humanitarian and human rights activist whose roster of honors includes the Nobel Peace Prize.

On Nov. 17, Wiesel will travel to Las Vegas to be honored by the Adelson Educational Campus for his literary accomplishments and human rights activities.

Wiesel, for all of his international accolades, reveals himself to be an easy conversationalist during a recent telephone interview from the New York City office of his foundation, The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity. His voice - one that should be instantly recognizable to anyone with even a passing interest in 20th century world history - is kind, pleasantly accented and punctuated with an occasional quick chuckle.

Above all, he is patient, graciously answering questions he surely has been asked thousands of times before and which, understandably, he might wish never to be asked again.

Wiesel was just 15 years old in May 1944 when he and his family were taken from their home in what is now Romania and deported to Auschwitz. His mother and younger sister died there.

Wiesel and his father later were transported to Buchenwald. His father died there shortly before the concentration camp's liberation in April 1945.

Does Wiesel ever wonder what his life would be like if fate - destiny, whatever - hadn't thrust him into the role of eyewitness to the Holocaust and, perhaps, humanity's conscience? Wiesel begins his answer by rejecting the latter part of the question.

"Conscience is personal," he says. "I'm nobody's conscience, and I would like all of those who read me and other teachers to feel the same way: Conscience is very personal."

However, Wiesel continues, "I occasionally ask myself that question. I would have remained in my little town, and my aspiration, really, was to become a teacher or the director of a Talmudic school - not a big one, just a small one."

"I'm still a teacher, just in a major town, and I write, and I tell the truth. I love to teach, because I love to study. In my classes, I'm the best student."

After the war, Wiesel spent several years as a journalist. However, he would wait 10 years before writing what would eventually become known in its English translation as "Night."

"I made a vow then to wait 10 years, because I was afraid I would not find the words," he explains.

Even in retrospect, it seems risky, if not emotionally dangerous, to share such an intense personal experience with the rest of the world.

"It was difficult," Wiesel says, to willingly be "plunged into the fire, into the shadows."

Was it courageous? "I think not courage," Wiesel answers. "That came much later, when I had to face the leaders of the world. I didn't know about courage, but afterward, that is what I read by commentators."

Wiesel says his biggest fear was of speaking the truth but having no one listen to it. Publisher after publisher rejected the manuscript.

"I've seen the letters: 'It's too sad,' things like that," Wiesel says with a quick laugh. " 'People don't want to read such things.' 'It's too macabre,' and that kind of thing."

Was it, perhaps, just a question of addressing the Holocaust too soon?

"It wasn't too soon," Wiesel says.

"But the trouble, maybe, was, why should a normal reader in New York or Paris believe that people were like that, that people did what they did to other people, to other human beings? That they created a universe called Auschwitz, that 10,000 people (a day) would be killed? Why would they believe it?"

The almost implausible monstrosity of the event was "exactly what these killers were counting on," Wiesel says. "By going too far, by embracing too much and daring to do things no other state has ever done, they felt the world won't believe, so they are immune."

In "Night," Wiesel writes that when their train stops at Auschwitz station, the deported Jews on board know nothing of the name's meaning and assume it to be merely a work camp.

"What pains me is at the end of May 1944, everyone knew the meaning of Auschwitz," Wiesel says. "They knew it in Rome, they knew it in Washington, they knew it in Stockholm, they knew it in London. Everybody knew it, except we Jews from Hungary didn't."

As Wiesel talks, it's a beautiful fall day in Las Vegas and (weather forecasts say) a breezy fall day in Manhattan. Does Wiesel ever find it tiresome to be asked - by, for instance, a reporter on the other side of the country - to recall experiences he'd rather not be reminded of nearly every day?

Wiesel laughs. "Again, I feel some empathy for my former profession," he says.

But, he continues, "I don't talk about it every day."

He pauses.

"I think about it every day."

After all he has experienced, how has he held on to his faith, his hope, his optimism?

"I find hope in children, all children," he says. "I owe them my hope. My students, I owe them my hope."

Yet, more than a half-century later, genocides and political repression still occur, hatred still exists and even Holocaust deniers and neo-Nazis remain. Does it ever seem futile?

"Never," Wiesel says. "You are witness. You just bear witness. If it were futile, you would stop.

"A few years ago, I was invited to the United Nations General Assembly, which I accepted. And the title of my talk was, 'Will the World Ever Learn?'

"I answered, no, it will not, because it hasn't. If it had learned, there would have been no Rwanda, no Cambodia, no mass murders. Children wouldn't die of hunger. And, yet, we must continue."

What is it that can make humans behave in such monstrous ways?

"I think I know the question," he says. "I do not know the answer."

But, he continues, "the main thing is education. Whatever the answer is to these questions, education must be a major component."

Does he worry what will happen when the generation that witnessed the Holocaust firsthand passes away?

"I believe anyone who is witness to a witness becomes one," Wiesel answers. "That is our hope and our trust. Therefore, in this case, I am confident."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.

BENEFIT

Elie Wiesel will be honored by the Adelson Educational Campus Nov. 17 during its eighth annual Pursuit of Excellence gala. The event will begin at 6:30 p.m. at The Venetian, 3355 Las Vegas Blvd. South.

Wiesel will receive the organization's Pursuit of Excellence Award for his literary accomplishments and activism in humanitarian causes. Proceeds from the event will benefit the school's scholarship program for students in need.

Tickets begin at $250. To purchase tickets or make a donation, call 515-8203 or visit adelsoncampus.org.