‘It encourages me’: Tribal educational center aims to close achievement gaps

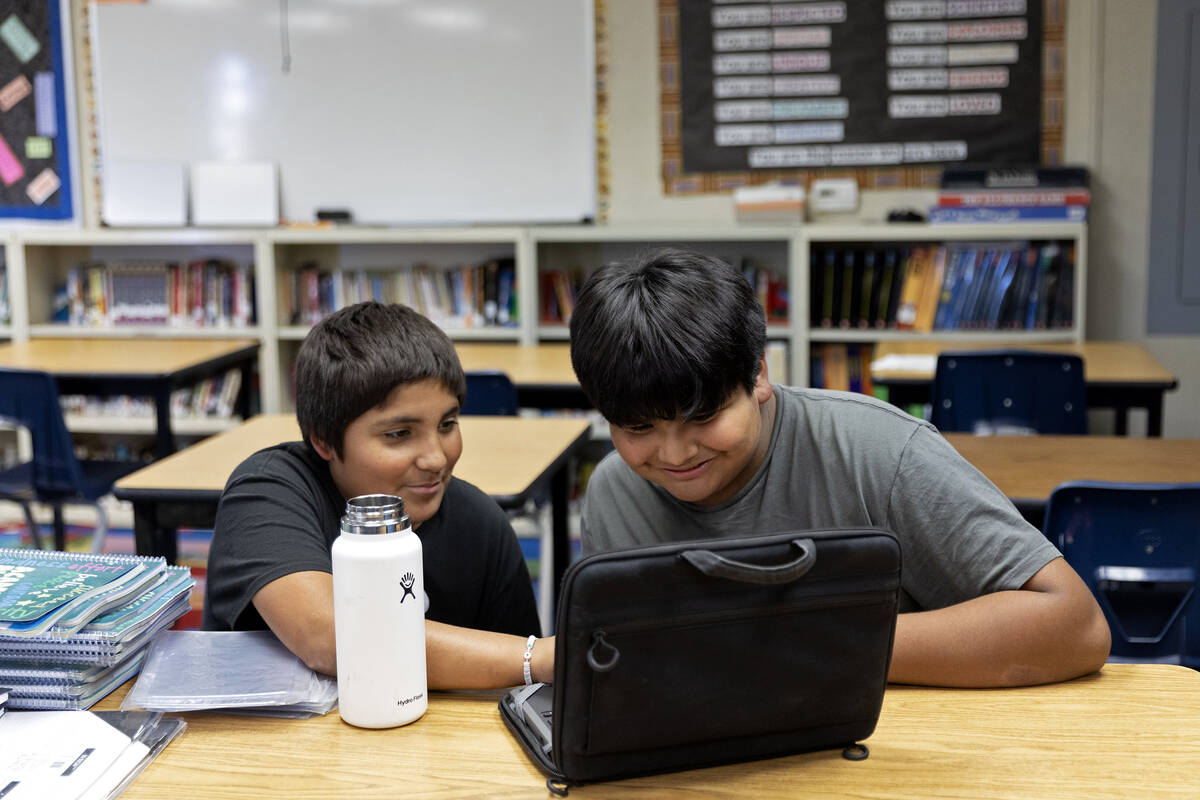

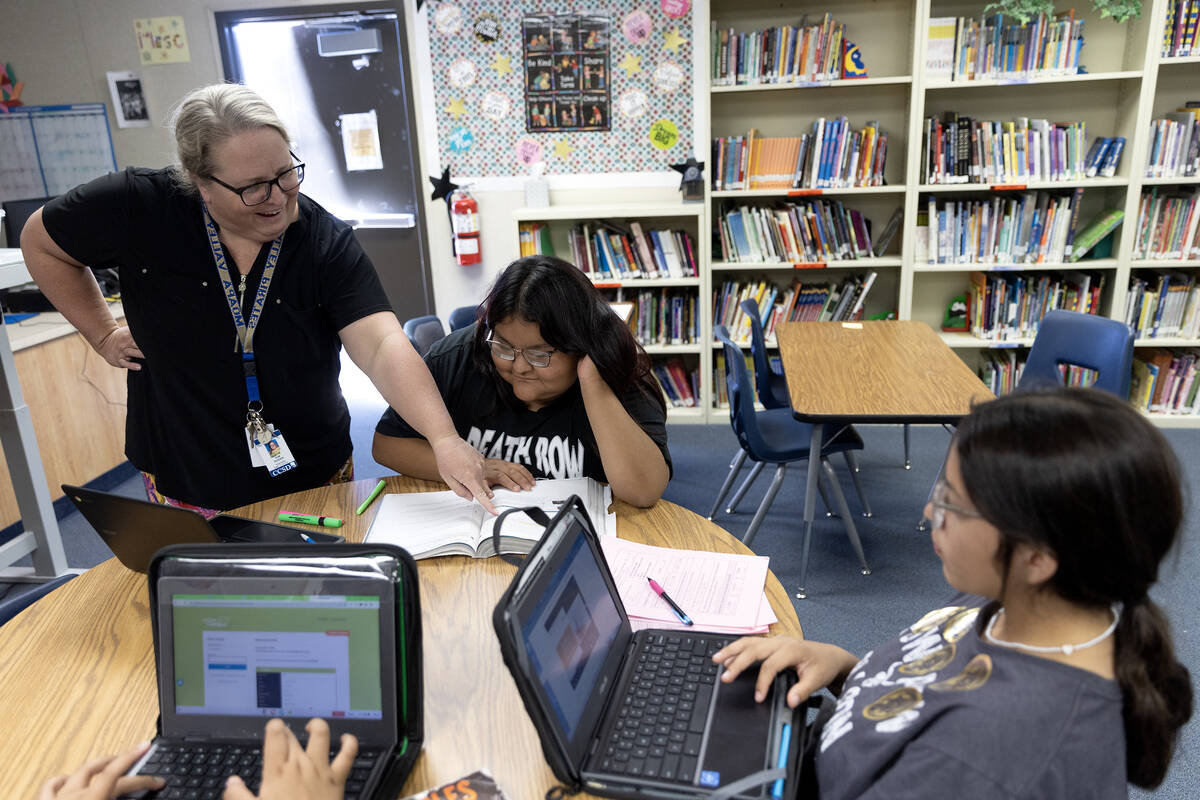

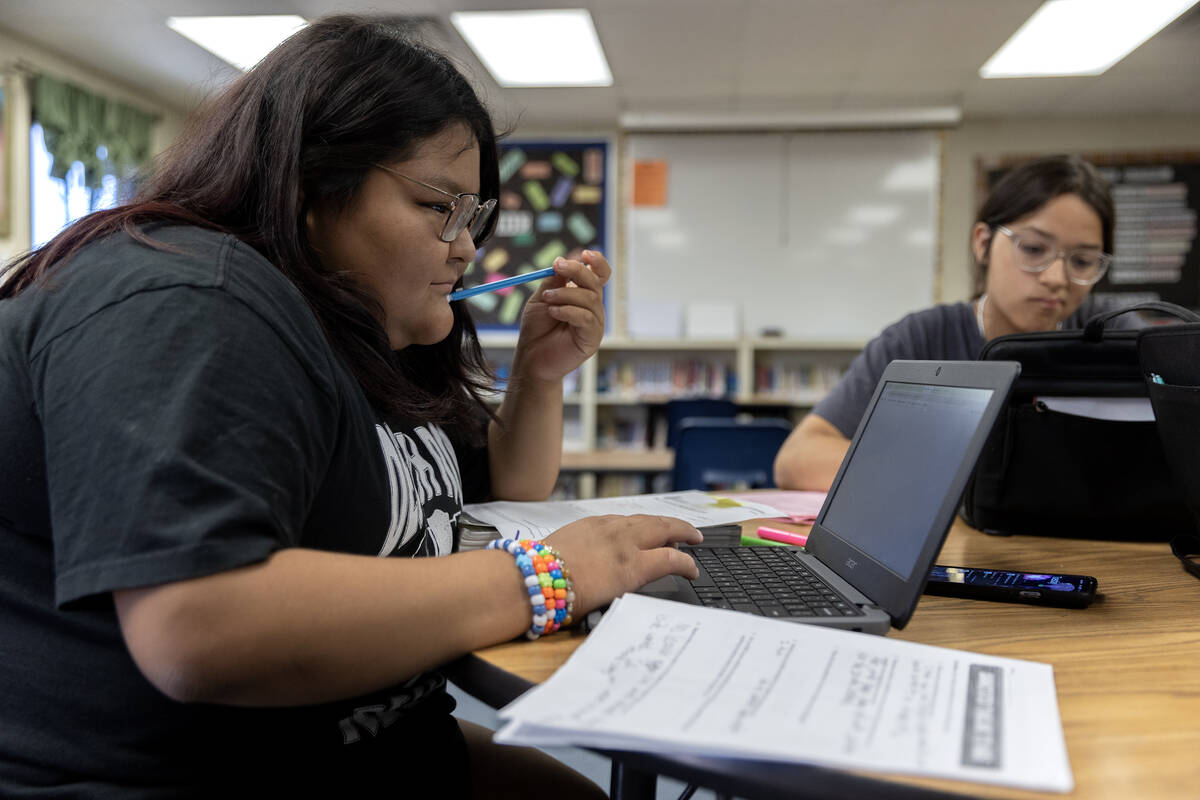

On the Moapa Indian Reservation, a school bus dropped off a handful of students who made their way into a portable building equipped with computer labs and a library. The children plopped their bookbags down at a table, opened up their laptops and got to work.

The Moapa Educational Support Center, located on the reservation of the Moapa Band of Paiutes, has served as a study hall, tutoring program and resource center for students for years. The center, run by the Clark County School District, reopened last year after it was shut down due to COVID, but has been working to raise awareness and bring more students and teachers to the building.

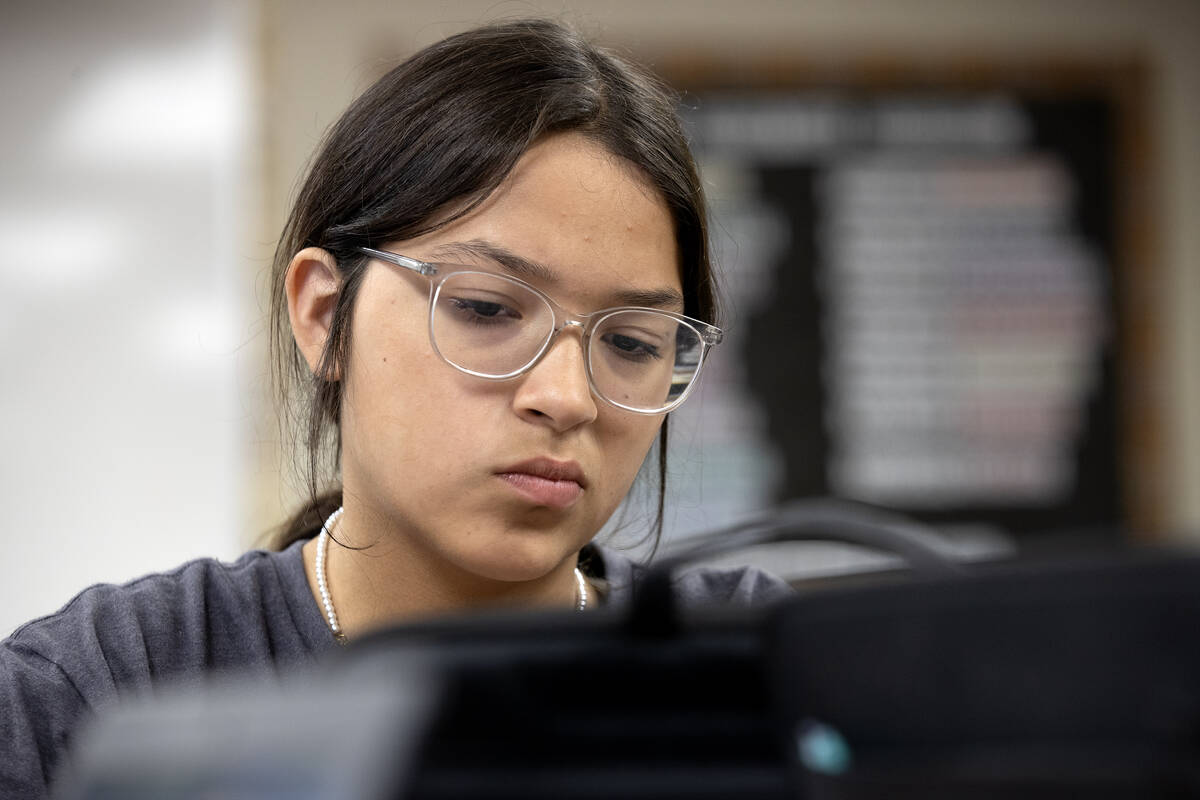

Aiyana Jim, a junior at Moapa Valley High School, has been going to the center since she was in middle school.

“It encourages me to do my work and turn in my stuff on time,” Jim said.

The support of a community

The center, open Mondays and Tuesdays from 2 to 5 p.m., provides a safe space for students to complete their work, according to Richard Savage, the coordinator of Clark County School District’s Indian Education Opportunities Program.

The center’s goal is to close achievement gaps, increase graduation rates and increase student and parent engagement. Some students just need more time to complete assignments, and home isn’t always the best place to get schoolwork done, he said.

“You’re working with the tools that you’re given,” said Savage, who is a member of the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe and was the first in his family to go to college. “Sometimes those needs in the academic world aren’t always met. … What they’re getting today is community support.”

Besides offering tutoring, the center also aims to help students be more college ready, Savage said, such as teaching them how to fill out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Savage also plans to host cultural events and get more parents involved.

The support center was first created around 2005 after Linda Young, the then-district director of equity and diversity education, learned that many high school seniors of the Moapa and Las Vegas Paiute tribes were dropping out, said Thelma Myers, the chairman of the Moapa Education Committee, which works with the school district as part of the Indian Education Opportunities Program.

The tribe signed an agreement with the Clark County School District to run the center, and the Moapa Education Committee has seen student growth and graduation rates increase ever since, Myers said.

The graduation rate for American Indian and Alaska Native students has grown by almost 20 percentage points since 2005, from 50.6 percent to 69.1 percent in 2022.

But achievement gaps remain.

The Clark County School District saw a drop of 3 percentage points in graduation rates for American Indian/Alaska Native students in the 2022 school year, while the graduation rate for students who identify as white increased by 1.1 percentage point to 86.1 percent.

Continued hurdles

With Nevada and about 36 other states facing a teacher shortage, that lack is felt also in Indian Country, which are often rural and isolated areas, according to Stacey Montooth, the executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission.

The center was once open three to four days a week, but it has struggled with recruiting teachers to the reservation, which is a 50-minute drive from Las Vegas and a 25-minute drive from the Moapa Valley High School, across the I-15. The Moapa Education Committee is working with the district to figure out if they can hire retired teachers or substitute teachers to come out to the center, Myers said.

Special education students in Moapa also have to travel all the way to Grant Bowler Elementary, about a 21-minute drive away, because they have a special education teacher. Myers wishes the Perkins Elementary School, which is about a seven-minute drive from the reservation, had a special education teacher.

“We don’t want our kids traveling so far out there,” Myers said.

Montooth said there isn’t a lot of cultural awareness from school staff regarding the intricacies of Indian education, from the history of the boarding schools to the continued marginalization of Native American communities.

“Unfortunately stereotypes often play a part, and our kids come into these classrooms and sometimes the educators have predetermined that they are not high achieving,” she said.

Research shows that students learn better and their education is more effective if they are taught by people who look like them, Montooth said, and there might not be many — if any — Native teachers that work at the school.

In the 2022-2023 school year, Native Americans made up 0.6 percent of licensed staff in the Clark County School District, according to data from the district.

“Learning is such an intimate experience,” Montooth said. “There certainly is not a one side fits all, especially in Indian country. It’s critical to have professionals who can address all these varying aspects.”

‘History of distrust’

At the support center, a shelf of globes sit underneath posters portraying Native Americans and their varying cultures from different regions of the United States.

With textbooks and laptops open, students completed worksheets and giggled with each other as their tutor, Kim Roden, a teacher at Moapa Valley High School, encouraged them to complete their work.

But closing achievement gaps for these students also requires acknowledging the current and historical barriers that exist for Native Americans in public schools. The biggest barrier they face in regard to education is the past, Montooth said.

For more than 90 years, the federal government engaged in forced assimilation of Native American children, taking them to boarding schools where they were taught how to integrate into mainstream culture by suppressing their Indigenous identities, languages and beliefs.

Because of that, “there’s a long history of distrust in the education system,” Montooth said.

Native American students come with some baggage, Myers said, because many of their parents or grandparents come from that boarding school experience.

Myers, whose father attended an Indian boarding school, said many Native parents and grandparents handed down those experiences with educational experiences to their children, scarring families families deep down.

Because of that history, establishing trust is important with Indigenous communities, Montooth said. It takes more to establish a strong relationship than it does for other families.

Families need to see the district’s Indian Education Opportunities Program’s involvement with the students, and they need to see loyalty, and that the staff will stick around.

“They need to see that they can trust again,” Myers said.

Contact Jessica Hill at jehill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jess_hillyeah on X.