Year after year, late or no-show buses in the Clark County School District draw the ire of parents and students alike. One year the problem even prompted a parent to crack a school bus window in frustration over a late drop-off.

But the issue extends beyond the yellow bus that pulls up late to your curb or the driver behind the wheel: It’s fueled by a perennial shortage of licensed bus drivers and exacerbated by low employee morale, which likely contributes to driver absence rates ranging from roughly 9 percent to 12 percent on any given day.

From Aug. 13 to Feb. 13 of this school year, buses traveling to and from Clark County schools were tardy over 11,000 times, according to a Review-Journal analysis of district data. Those delays, self-reported by bus drivers and staff, have ranged from just one minute to over two hours, the records show.

The result: students stumbling into class late or not at all or grabbing breakfast from the cafeteria on the run.

But the story behind the late buses is far more complex than most parents and students appreciate. It begins every day as early as 4:30 a.m., where staff at the five district bus yards race the clock to fill empty routes.

No two days are the same.

Clark County schools and the late bus issue

(Mat Luschek / Review-Journal)

‘Slicing and dicing’

At 5:15 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, staff at the Russell Bus Yard in Henderson had 43 bus routes with no driver. The goal: fill them within 30 minutes.

Routes go unfilled for one of two reasons: either because of the district’s overall shortage or drivers who call in sick.

Those numbers vary throughout the week or year. At the start of this school year, the district had 72 vacancies. As of Feb. 11, it had 98.

“There’s just a lot of moving parts … and all of those moving parts are extremely time sensitive,” said Shannon Evans, director of the district’s transportation department. “So there’s that working against us.”

Substitute drivers listed on “extra boards” help cover the gaps, coming in every day without knowing where they’ll end up. But often, there aren’t enough of them to cover the holes.

That’s when staff resort to a complicated technique called “slicing and dicing.” They break a route into pieces and distribute them to nearby drivers willing to make an extra run.

It’s a hectic, on-the-fly approach — and it happens every day.

How often are buses late at your child’s school?

Enter the school name below to see the tardy rate from Aug. 13-Feb. 13 of the current academic year.

**This analysis excludes field trips, Miley Achievement Center, Helen J. Stewart, Desert Rose, John F. Miller, Variety, West Prep and child development centers. Data for some schools showed zero minutes for some bus delays.

School Profile:

Educational impact

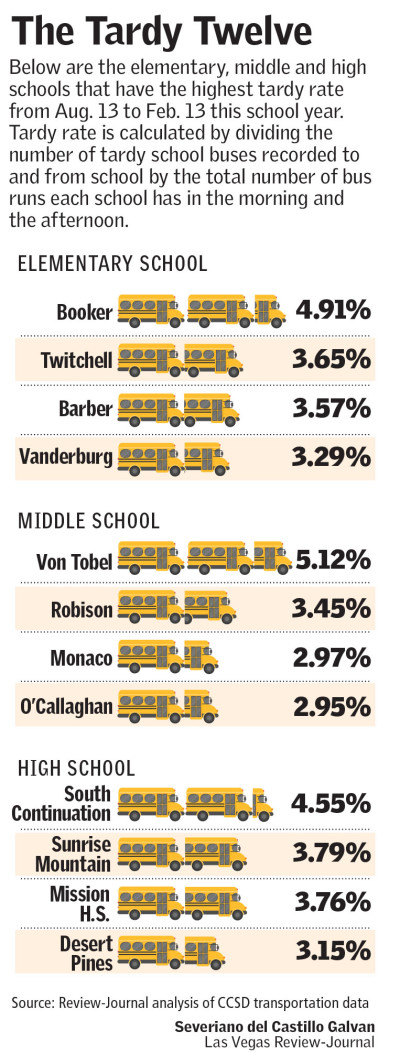

The Review-Journal analysis of tardy data found the elementary, middle and high schools that have been most impacted this year by late buses either dropping students off at school or at home.

The top four in each category, a group we’ve labeled the Tardy Twelve, includes Von Tobel Middle School, which had 81 tardies that were an average of 33 minutes late, and Desert Pines High School, which had 174 late buses that ran an average of 24 minutes late.

The self-reported figures are likely flawed, as some drivers may not report that they’re running late. But the district is working on launching a phone application in August that will allow parents and students to track the location of buses in real time. The app also will give the district a more precise way to monitor the depth of the problem.

The district also is looking to partner with the Regional Transportation Commission, Evans said, to potentially provide students with better access to public transit.

Innovations like that can’t come soon enough for Sierra Vista High School Principal John Anzalone.

He said the problem with late buses became so bad that he rearranged this year’s schedule so that elective classes are held at the beginning of the day. That way, students arriving late would not miss instruction in core classes.

That is paying dividends, he said, as the problem is the worst he’s seen.

“We’ve had numerous parents go to the stop, pick their kids up and drive to the school,” Anzalone said. “We’ve had parents come in and say, ‘You know what, I literally drove past a bus stop at 8:30, 8:45, 9 o’clock and the kids are still sitting at the bus stop.’ We’ve had kids walk to school because they didn’t want to miss school and show up at 10 o’clock.”

And kids who receive free breakfast at school may come in even later, he said.

It’s an issue that Clark County School Board Trustee Danielle Ford knows firsthand. She drops her son, Logan, off at a bus stop for Canarelli Middle School for magnet-school students.

“It’s always a surprise what time the bus is going to come,” she said. “In my work life, I’ve had to change my schedule around, and I can’t do any work earlier than 8:30, 9 o’clock because I don’t know if I’m going to have to drive him to school or if I’m going to wait there.”

It’s an issue that she wishes the School Board would take more seriously.

After a lengthy work session in February in which board members argued at length over who should sit on which committees, Ford raised the subject and chided her colleagues.

“We’ve spent an hour and 40 minutes (talking) about ourselves and not talking about things like why my son got to school 20 minutes after it started,” she said.

‘They run you like crazy’

Erica Smith was trying to get an elementary student to sit down while driving her bus last year when he got so angry that he tried to jump out of the back door.

She pulled the bus over and had to wrestle with the child for 30 minutes, she said, and ended up injuring spinal discs in her lower back. She’s still seeking payment for her medical costs from the district, she said.

Smith works two jobs to make ends meet. Like many other support staff, she also struggles with increasing health insurance costs.

“We’re overworked,” she said, noting that drivers may be pulled to cover a route elsewhere on any given day. “People quit. They can’t keep everybody. They run you like crazy.”

Drivers call out on Thursdays and Fridays in particular, she said, because they’re tired.

“They get frustrated, they get tired, and that’s their way of saying, ‘OK, we’ve had enough,’ ” she said.

The job also requires drivers to split their workday between pick-up and drop-off times, but doesn’t guarantee a full eight hours of work each day.

If drivers got a full eight hours of work every day and better pay, she said, more would likely stay on the job.

But Alesha Grey, who started driving in the district in 2005, said staying in the job is about more than salary.

“I believe that drivers, when they find the ‘why’ in why they do their job, then they’ll just come around,” she said.

For Grey, the reason is personal. She grew up in Las Vegas as a homeless teenager who dropped out of high school and can relate to the challenges of the students she picks up.

“I wanted to do the best job that I could do when I grew up,” she said. “I knew I wanted to go out there and make a difference.”

Driving buses even prompted her to get her GED and pursue higher education, so she could help students when they asked her questions about their homework.

Grey wants to tell parents that their children are in the hands of caring people.

“But just have patience with us,” she said. “We’re just doing the best job that we can do to make sure their children get to school safely and in a timely manner.”

National shortage

The bus driver shortage is a nationwide issue.

In a survey of 486 districts by School Transportation News magazine, 74 percent said their operation was currently short drivers. Fifty-three percent of 357 respondents said pay rates were negatively affecting driver retention.

Las Vegas schools may face even steeper competition than many areas. Other employers looking for commercially licensed drivers offer jobs that may be more enticing than an entry-level, nine-month-a-year gig.

“The tourism side of what this city offers never closes,” said Shannon Evans, director of the district’s transportation department. “And so in contrast to that, when you have people that come to work for us for nine months and yet the tourism is offering 12 months — as many hours as you want to work — yeah, it’s a viable competitor.”

It already invests roughly $1,800 per driver for training, according to Evans.

Yet there’s nothing to stop new hires, who make $15.30 an hour, to leave for higher paying jobs. Staff at the Russell yard recently saw four drivers leave for jobs with Republic Services at what they said was twice the pay.

“But we’re carrying very precious cargo and they’re not. They’re carrying trash,” said Dan Romero, a transportation operations manager. “See the difference?”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.