Middle ground hard to find on school tax issue

A fuse in the 50-year-old electrical system caught fire, shutting down Clark High School until crews could reroute electricity. They accomplished the task in one long night because of mandatory testing the next day.

That was just the latest.

Although Clark is the valley's Academy of Science, its labs consisted of tacked-on islands where students leaned around pillars of gas and water lines to see the teacher. And the school was short on computer labs, despite also being the Academy of Math and Applied Technology.

That was last year, before the school built in 1964 scrounged for the last few million dollars of the Clark County School District's $4.9 billion capital projects program, initiated in 1998.

The school's modernization is just finishing up, most headaches over; but 40 other schools facing similar struggles have put their hopes into the next capital program.

Will it happen? Should it happen?

The answer is up to those who vote in the Nov. 6 election. They have been posed the polarizing question of whether to raise property taxes by $74.28 annually for a home with a $100,000 assessed value.

Rates would stay there for six years to produce an estimated $669 million for infrastructure upgrades, modernizations and construction at schools like Clark.

Is the district's request justified at a time like this? Do schools need, or just want, new equipment and modernized campuses? And don't schools get funding for maintenance?

PRO AND CON

No one is better at shedding light on these questions than Associate Superintendent of Facilities Paul Gerner, who is in charge of keeping schools up and running, and conservative think tank Nevada Policy Research Institute, the only organized opposition.

Victor Joecks, NPRI spokesman, said this tax increase could push struggling homeowners over the edge, and the valley is already battling one of the worst foreclosure rates in the nation. Plus, he said, these 40 schools have been "well funded," having received $490 million in investments since 1994.

But Gerner disagrees, and explains why. "We're paying now because we didn't pay before," he said.

By "we" he means the state, which gives the district little funding to maintain schools. Therefore, only 10 percent of what his workers do is preventive maintenance, when it should be 75 percent.

Most of what they do is corrective, fixing things as they break because his staff is stretched so thin, Gerner said. Therefore, things like industrial air conditioners, and schools altogether, tend not to reach their average life spans.

But Gerner obviously has a dog in the fight. Almost all of the $669 million tax increase would land in his department.

He isn't wrong about the funding situation though.

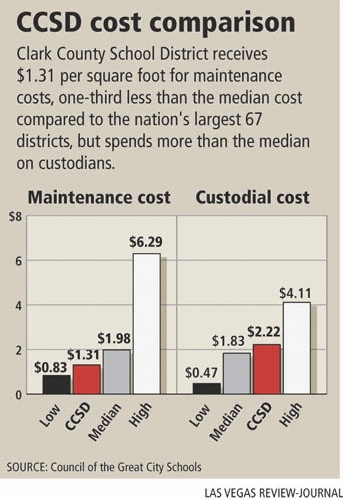

The district receives a third less in maintenance funding compared to the median for America's 67 largest school districts, according to the Council of the Great City Schools' October report. Clark County spends $1.31 per square foot for maintenance, short of the $1.98 industry standard.

With 35 million square feet of buildings, the district, fifth largest in the country with 357 schools, would receive $23.5 million more if maintenance funding matched the industry norm.

School officials tried to pinch pennies last school year, finding that custodians were overpaid to the tune of $2.22 per square foot. The industry median is $1.83. A consultant said the district could save $10 million a year by outsourcing, but that has been put off. To reach a contract with the Education Support Employees Association, a union representing custodians, district officials agreed to not outsource for three years.

But Clark County schools shouldn't need that much maintenance, argued Joecks. NPRI has opposed the tax increase, bringing a case to the state Supreme Court trying to get it thrown out.

CALCULATING THE NEED

Clark County schools are 22 years old on average compared to the country's average of 50 years, Joecks said.

But the one-third of schools in "desperate need of major renovations" are 30 years old, district officials say. And the schools' conditions aren't debatable, said Joyce Haldeman, associate superintendent of community and government relations.

Each school is tracked and has a Facility Condition Index number between zero and one. The number is a ratio comparing the cost to renovate versus replace. An index of 1 means the condition - whether it's a school or an individual piece of equipment - is so bad the cost to replace is the same as the cost to keep renovating. District policy is to begin replacing things in the range of 0.4 to 0.6, when the cost to renovate is about half the cost to outright replace with something new.

Some of the schools on the tax increase list are projected to be beyond that range within the next five years. Three schools would be between 0.90 and 0.99.

Worst-case scenario, as many as 30 schools must be closed in the next few years if the tax increase fails . It's not that schools would fall down. It could be something unexpected, another electric flare-up or a broken air conditioner beyond being patched up.

If students can't go to school for even a week, they can't simply sit out but must be transferred to another school, which is a problem itself.

Haldeman said these surprises are why the list of schools to benefit from the tax increase is "fluid," a statement which has irked critics like the research institute, which calls the tax increase measure a "bait and switch."

"This is kind of what you see in a death spiral situation," said Gerner, noting that the dismal maintenance funding has always been this way. "But the 1998 bond hid that sin for so many years."

DISTRICT'S BOND HISTORY

The district relied on the 1998 bond program not only to build 101 schools to accommodate Clark County's unprecedented growth throughout the past decade but also to pay for renovations. A third of the bond, which brought in $4.9 billion over 12 years, was used to renovate and modernize 229 existing schools. Also, $1.6 billion was used to replace older schools.

The end of that bond has revealed a tremendous shortfall in maintenance funding, said Gerner, who warned the district a couple of years ago it could happen. But the School Board held off on seeking another bond in 2008 and 2010, waiting for an economic recovery that has been slow to arrive.

If the measure passes Nov. 6, a property tax increase would get the district by, but it's a bandage to stop the bleeding, Gerner argued. Lift the bandage, and the district's still bleeding.

The money would be spent on improvement projects such as modernizing 18 schools, replacing six schools' climate control systems, upgrading 10 electrical systems, building four gyms and replacing two schools. But district officials have been clear that other schools are in need, too.

However, Joecks argued that the district was reckless with the previous bond, writing a $5 million check to The Smith Center for the Performing Arts and giving $1 million to Henderson for a city pool, and shouldn't be given another blank check.

School officials said those two checks saved the district money in the long run. For example, it didn't have to build and maintain lap pools at new Henderson high schools, which would have cost millions of dollars.

Also, The Smith Center will provide 60 performances for as many as 108,000 students per year. The district will be provided priority access to performance spaces. The center will also provide professional development workshops for teachers at no charge for five years, according to a contract.

Looking forward, this tax increase won't be the last, if passed. It's a "bridge" because property values are too low for a multibillion-dollar bond until 2018, district officials have said.

Even Clark High School didn't get everything it needed from the 1998 bond. Most of the modernization went to $23.8 million on infrastructure, replacing 50-year-old roofs, electrical, plumbing and air-conditioning systems. None of the money went to instruction. And it still couldn't afford a computer lab.

"The district's answer was a consistent, 'No. No. No,' " Gerner said.

So, Principal Jill Pendleton reached out to ABC late-night talk show host Jimmy Kimmel, an alumnus. She received a $54,000 check that will soon buy more than 70 computers.

"Not every school has Jimmy Kimmel for an alumni," Gerner pointed out. "Could get pretty rough."

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.