UNLV’s research could draw new industries

Could hibernating squirrels help reawaken the Las Vegas economy?

Diversification has become the favorite buzzword for weaning the valley from the reliance on tourism and construction that has proven so painful during the past three years. And the University of Nevada, Las Vegas is trying to chip in by resuscitating the effort to commercialize some of its research. UNLV hopes laboratory work, such as studies of how hibernation traits in other animals could improve the results of human organ transplants, will lead to spinoff companies that build the technology industries the city has long craved.

"This is part of what we need to remake Las Vegas," said John Laub, head of the Nevada Biotechnology and Bioscience Consortium, who has pushed several years for technology transfer programs. "If we don't do it and things stay the same, we will end up being the Detroit of the West Coast."

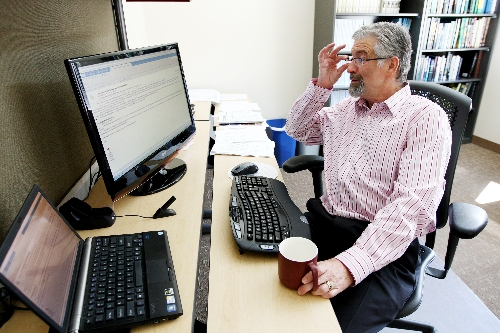

UNLV formerly had a one-person office to promote technology transfers, but it was swept away by budget cuts last year. Even then, said Stan Smith, UNLV's associate vice president for research, one person could not accomplish much because he had to split his time between finding projects with business potential and lining up financial and legal help on the outside.

In March, UNLV launched an Intellectual Property Committee that includes five faculty members who vote plus a related ex officio panel composed of school officials and businesspeople.

"We will try to encourage practical thinking as much as possible," said Smith, who leads the ex officio committee. "But we also have to respect the concept of faculty freedom" that allows research even with no apparent practical applications.

As is true with much of technology, many university innovations and ideas do not find profitable markets. But according to the Association of University Technology Managers, 435 of the 596 university-spawned companies launched in 2009 stayed within the home state, the type of payoff technology transfer advocates hope for.

However, even if the committee makes headway it would not provide immediate relief for a local unemployment rate that's near 14 percent. Phyl Speser, the CEO of the consulting firm Foresight Science & Technology in Providence, R.I., said he advises clients to set a goal a decade out then work backward to devise a realistic method for reaching it.

"One year, forget it," he said. "Two years, forget it. Five years, you may start to see some results. You have to think of a 10-year program."

Even then, he said, the bulk of the jobs will not come from research but from manufacturing.

Also, said Nikki Borman, a consultant in Holliston, Mass., a university needs resources not only to get the job done but to portray to scientists elsewhere that it is serious.

"If you only have part-time people, that shows you don't have a lot of confidence to do it," she said. "You have to make a commitment."

In that respect, UNLV's renewed effort starts well behind the curve.

"As we try to reinvigorate technology transfer, unfortunately there isn't any funding," Smith said.

The committee is designed as a part-time, volunteer effort that can survive the tightening budgets UNLV faces. By contrast, several nearby programs have far more money and muscle behind them, even excluding the giants in California. These include:

■ Arizona Technology Enterprises, tied to Arizona State University, with a full-time staff of 15.

■ The University of Arizona office of technology transfer. It has a staff of 13 plus access to a university-owned business park, with facilities designed for new companies.

■ The University of Utah technology commercialization office has a staff of 28.

All three schools can tap into funds or private-industry ties that have been set up to help finance new companies that emerge from their laboratories. Utah's state government, for example, has approved injecting $179 million into the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative.

■ The University of Nevada, Reno, has three people in its technology transfer office.

Following the template of other universities that concentrate on a specific niche, Smith said UNLV's committee will focus on renewable-energy sources such as solar along with water management and conservation. Borman said the solar aspect holds promise because it is still less efficient and more expensive than burning fossil fuels, although the costs have declined in recent years.

Laub has also touted several biotechnology projects as possible seeds for Las Vegas-based industry.

To fulfill the ambition, he has scouted for private companies that could support promising innovations.

The current effort started about two years ago, Laub recalled, when Neal Smatresk showed an interest in technology transfer after becoming president of UNLV. About one year ago, after the permanent office was eliminated, the talk turned to the committee.

Once the committee identifies a promising concept, Smith said, the professor will get a year to come up with a prototype. If it appears viable, then the university will pay for patent protection and try to accelerate its development.

The latter phase is important, Smith said, "to avoid the valley of death, where you apply for a patent and then it just sits on a shelf."

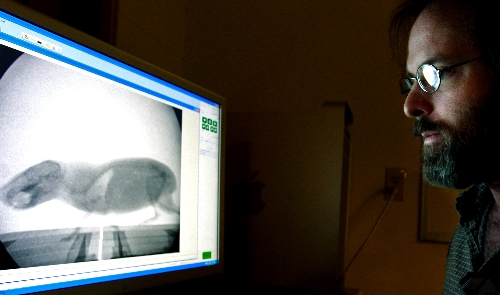

Even then, many researchers still do not think about commercialization. Associate professor Frank van Bruekelen, who is studying hibernation, understands his work's possible applications but does not work toward them. He sticks to basic research, something downplayed by the federal funding policies of the Bush administration.

"What that didn't take into account was that you can do a lot of things if you first understand the underlying processes," he said.

But assistant professor David Lee, who studies biolocomotion, said many avenues have some type of practical use. He pointed to the theoretical work Albert Einstein did on lasers in the 1940s.

Although the development of those working functional lasers took decades, lasers have now reached the point they are built into pens as pointers.

Biswajit "BJ" Das, an associate professor and director of UNLV's Nevada Nanotechnology Center, is perhaps the farthest along in technology transfer. UNLV licensed two approved and two pending patents based on his work to a separate company, Shivam Nanotechnology, to try to find commercial markets.

As a company partner, Das insisted that Shivam Nanotechnology remain in Las Vegas. But that has proven a handicap in the short run that could be a problem for others.

"I think if we went to California we would have had an easier start and moved more quickly," Das said.

West of the mountains lies a much deeper pool of investors, legal expertise, tech industry executives and people with advanced scientific and engineering training. However, Speser said, that infrastructure could fall into place if enough companies succeed.

It also takes more than exciting theories and patents to attract investors. Although Das has always aimed to find manufacturing applications for nanotechnology, investors have been lukewarm because they commit to tangible products and not the processes on paper that he has developed to date.

Contact reporter Tim O'Reiley at toreiley@lvbusinesspress.com or 702-387-5290.