Valley schools help Thailand student, other second-language learners

It was quite the crazy, cross-cultural scene: a 15-year-old student, a year and a half out of Thailand, beginning the first few pages of "To Kill a Mockingbird," an American classic.

Yet there he was at West Career and Technical Academy, a kid by the name of Chanchai Manisi, reading about racial injustice in the Deep South during the 1930s.

Or at least he was trying to.

He seems to have met his match in Harper Lee's novel, a good chunk of which is written in a Southern dialect.

"It's difficult," Chanchai said recently at the school on West Charleston Boulevard, west of the Las Vegas Beltway.

"It's hard for even me to understand, but we've gone through the first three chapters together," said his 68-year-old stepfather, Gary Burger, who hired a tutor to help the teen master English.

The federal No Child Left Behind Act requires public schools to monitor limited English speaking students and show them making progress. It's a mammoth task in the Clark County School District, where roughly one-third of more than 300,000 students are identified as English language learners. Among district students, 157 languages from 147 countries are spoken.

Both schools and students struggle to meet the federal mandate requiring evidence of annual improvement.

But Chanchai is no stranger to challenge.

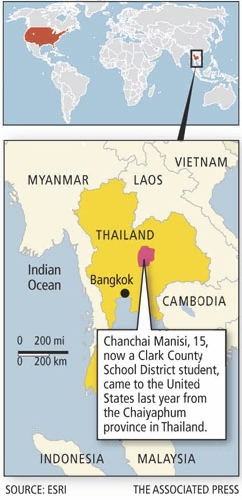

He lived with his grandmother for five years in a tiny village north of Bangkok before moving to Las Vegas to be with his mother, Rattana, 36, who married Burger. Mother and son recently became U.S. citizens.

His grasp of English improved quickly, so much so that he was named the Clark County School District's English Language Learner Student of the Year.

Michael Wood, Chanchai's English teacher, may even bring in the classic 1962 movie to make the story easier for the teen to understand.

Lori Figgins, who taught Chanchai the alphabet and his first English words at Rogich Middle School, suggested the family try to find a Thai version of the book, if it exists.

"That way," she said, "Chanchai could go back and forth from English to his own language, and he'd understand the plot."

Chanchai's struggle with language doesn't end with reading. He also is considering changing his first name. Classmates at times have a hard time pronouncing it, and his soccer coach has been calling him "Sean" for short because that's how the first part of his name sounds.

A DIVERSE DISTRICT

Only two schools of more than 350 in the district have no limited English students: Mount Charleston's Lundy Elementary School and Blue Diamond Elementary School in the southwest county.

What drives the diversity so apparent in Clark County schools?

It's the same diversity visible in the local workforce, said Norberta Anderson, director of the district's English Language Learner Program, or ELL. Almost 40 million visitors flock to Las Vegas annually, and their needs are met by an army of service industry workers bulked up by new immigrants who send their children to public schools.

"We have a workforce where not knowing English isn't a problem," Anderson said.

The district has more than 2,000 teachers trained or certified in teaching English as a second language, although Anderson said local schools are still shorthanded, a problem seen in schools across the nation.

"It's our civic duty to educate them, not ask them what they're doing here," Anderson said of students attempting to master English. "It's a shame that sometimes that's not considered, and there are some people who get upset by their presence. But this is America. We all came from immigrants, and our job is to make sure the kids have an opportunity to learn."

To that end, the district gets federal help: $6 million in funds from Title III, officially called the English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement Act. It pays for supplementary classroom materials, dictionaries in more than a dozen languages and the salaries of nearly a dozen specialists who train regular classroom teachers to work with limited English speakers.

One of the strategies passed on to regular teachers is that gestures are paramount in working with English language learners. Instruction often can morph into a game of charades, said Laurie Daly, an ELL teacher at Spring Valley High School.

"Think back when you took your first foreign language class," she says. "It's much of the same thing. We use flash cards, and we play all sorts of games. It's like starting from scratch."

And understanding the cultural backgrounds of your students is equally important, Daly added.

Nearly all district ELL teachers have either studied or come across the book, "Gestures: The Do's and Taboos of Body Language Around the World."

It's a book that Anderson wants all her teachers to know well. She keeps it available at the ELL program office.

In Thailand, for example, people bow with hands clasped together in prayer-like fashion when meeting or parting. The higher the fingertips, the greater respect shown, although the fingertips are never supposed to be as high as the face.

That's what Chanchai has been doing around his high school.

MAKING A NEW HOME

These days, Chanchai is adjusting to his new home, a few blocks north of the Red Rock Resort. It's a far cry from his old house, which sat on stilts in the middle of a rice field in a village called Kaset Sombun in the province of Chaiyaphum in northeast Thailand.

To get into his new home inside the gated community, Chanchai must now push a series of numbers, and presto, a phrase truly foreign to him at this stage of learning English.

If Burger, a retired police officer from Los Angeles, hadn't met Chanchai's mother nearly a decade ago while on vacation in Thailand, it's likely the teen would have ended up working in the rice fields of his village.

As it is, he is learning English, taking a host of other classes, including graphic design and biology, and playing soccer for Palo Verde High School's junior varsity team. West Academy doesn't offer team sports.

"The kid loves it here," Burger said. "He says he don't ever wanna go back."

The teen's mother said she's happy she met Burger.

He took her away from factory work in Bangkok. She began working in factories at 12, and over the years, developed back problems.

At night, she studies English in an adult language program offered at an elementary school.

As for her son, he is up to his neck in homework, which can prove difficult at times because of his limited English.

But math isn't hard. That comes fairly easily.

Chanchai's middle school teacher, Figgins, recalls the time she accidentally handed him a piece of paper that happened to have her daughter's college math problems on the back of it.

He started solving the calculus problems, she said.

It was strange because he was having problems with his algebra, but it turns out the difficulty stemmed from not knowing English and being unable to read the instructions to the questions.

"Here he was doing my daughter's math work," she said. "It was an amazing thing to see."

Contact reporter Tom Ragan at tragan @reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512.