Cooling stations can prevent heat-related deaths. But do Las Vegans use them?

Offering a respite from the sweltering desert heat, cooling centers can mean the difference between life and death for victims of heat illness. But that’s only if they use one.

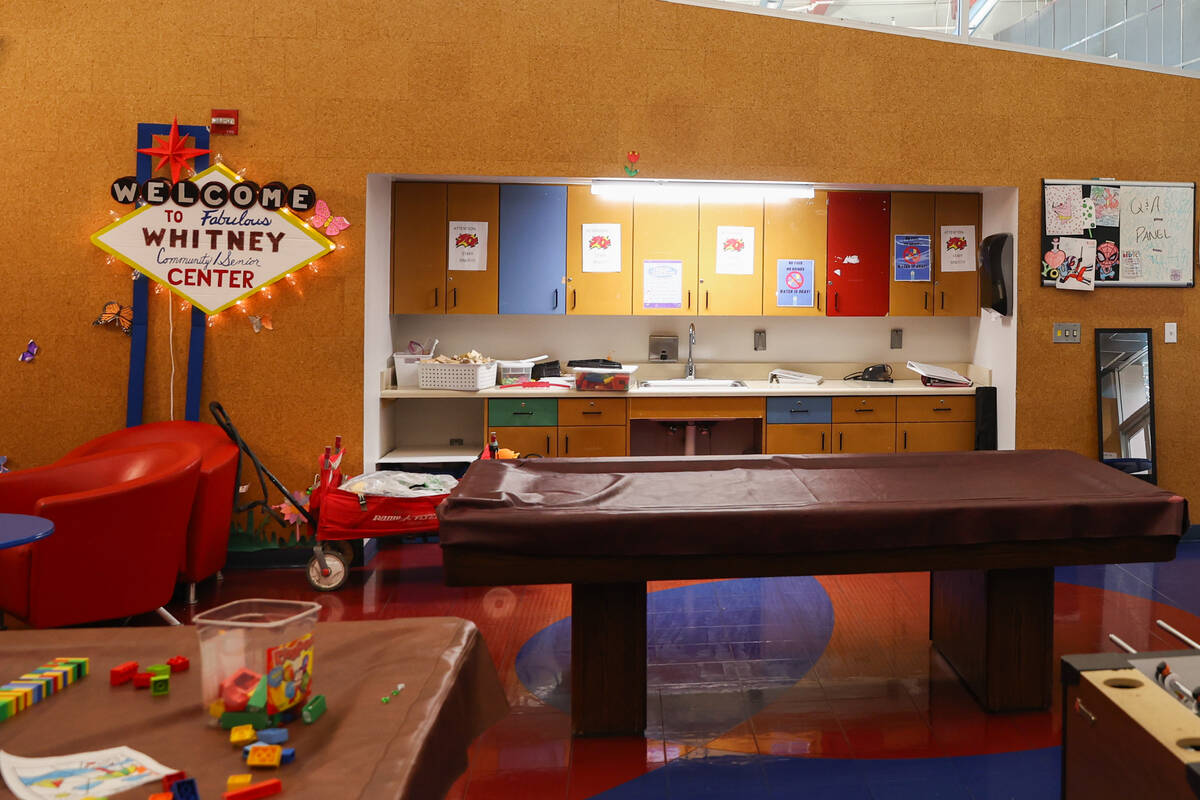

A new report from the Desert Research Institute’s Nevada Heat Lab takes a closer look at the effectiveness of the region’s cooling stations. Those air-conditioned buildings throughout Southern Nevada — mostly community centers and libraries — open their doors to the community when the National Weather Service issues an extreme heat warning.

Heat remains a concern for Southern Nevada, where 527 people died last year because of extreme temperatures. This year, 87 people have died so far in the heat in a summer that’s been more mild by comparison. Despite the cooler summer, Nevada’s two urban centers still rank as the two fastest-warming cities in the nation when observing temperatures since 1970.

Related: The Nevada Heat Lab is working to save your life

When the survey asked how frequently people used cooling stations, many didn’t realize that was one of the purposes of that building, said David Almanza, a postdoctoral researcher at the Nevada Heat Lab. Across almost all of Southern Nevada’s 40 or so cooling stations, researchers asked anyone inside, including those who may not have sought out cooling intentionally.

“People started writing ‘never,’” Almanza said, adding that the team began tallying separately the responses of people who didn’t know they were using a cooling station. “What that tells us is that many people who are in these spaces don’t realize there’s a service being provided.”

Better communication needed

One highlight of the report is that only 17 cooling stations regularly have enough people to report above 70 percent capacity.

The centers vary in what services they offer, such as homelessness assistance, health services and water. Some of the more frequently listed reasons as to why people chose a particular location include free access, the ability to bring children, and proximity to homes or public transit.

Ten survey respondents said their cooling station decided to turn people away, for reasons like the facility being over capacity, unruly behavior or a lack of available water. To best get the word out, the most suggested methods of promotion were street advertisements and word of mouth.

Encouraging every cooling station to have visible signs and water is one result of the survey, Almanza said. In the future, cooling stations also may have emergency medical personnel available to assist those suffering from heat illness.

And that’s the mission of the heat lab — to produce studies that show the need for better responses to urban heat, Almanza said.

“That’s one of the goals of the studies and reports that we’re putting out: to encourage everyone, including decision-makers, to see these mitigation efforts not as passive amenities, but as active infrastructure of public health and safety,” Almanza said.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.