Nevada road projects run out of funds

There is no figurative piggy bank to break, no jockey box to rifle through, no couch cushions to search between.

Truth is, the funding of state road construction during tough economic times - as in everyday life during any financial downturn - requires tough calls when there's only so much money in your checking account.

Call it managing one's budget.

Call it putting pencil to paper on the cost of every layer of asphalt being laid.

That is where the Nevada Department of Transportation finds itself as 2013 gets under way. Projects on the drawing board well before the nation, and Southern Nevada, began its free fall into recession are now getting a hard second look as to whether they're really necessary.

Or, specifically, as necessary as others.

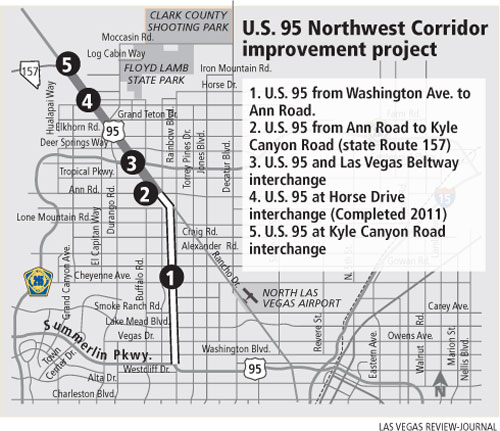

Take the five-phase U.S. 95 Northwest Corridor Improvements Project, for example, which now finds itself on hold.

In an effort to ease the congested commute into the booming northwest valley, the Transportation Department received approval in January 2000 for expansion of 12 miles of U.S. 95 from Washington Avenue north to state Route 157, known as Kyle Canyon Road.

The project would add lanes to U.S. 95, construct interchanges at Horse Drive and Kyle Canyon Road and a system-to-system interchange between U.S. 95 and Clark County 215, the northern segment of the Las Vegas Beltway. Also to be included were auxiliary lanes, ramp improvements, ramp metering, and landscape and aesthetic improvements.

Projected cost at the time: upward of $550 million.

Federal and state funds totaling approximately $75 million were allocated for Phase 1, which consisted of widening seven miles of highway between Washington and Ann Road, while $56 million in funds supplied by the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada were used in Phase 4, the interchange at Horse. Work on the two phases was to be handled concurrently.

Then the recession hit.

While the funded construction started in 2010 as planned, with the interchange at Horse completed in 2011 and the 2½-year widening between Washington and Ann to be wrapped by the end of this month, phases 2, 3 and 5 are pushed back until 2015, at the earliest.

Phase 2, the widening of the five-mile stretch of U.S. 95 from Ann to Kyle Canyon Road, which originally was planned to start this year, was projected to cost between $81 million and $92 million.

Phase 3, the construction of the U.S. 95-Beltway interchange, would run between $233 million and $290 million.

Phase 5, an interchange at Kyle Canyon, would come in at a relatively inexpensive $40 million.

That was the cost projections as established in 2000, with the high ends taking into account inflation by the time of their completion.

There is no telling how much the respective phases may cost if Phase 3 doesn't start until 2015. Or beyond.

"This is one of the projects we'll have to move out" of the 2013 calendar, said Tracy Larkin-Thomason, the Transportation Department's District 1 deputy director. "I expect it to be in '15, or maybe '16. But it will be moved out to future years."

'IT'S A CHALLENGE, FINANCIALLY'

Because road construction projects, especially ones using interstates and state highways, are proposed and planned well in advance, there is never a guarantee the full funding will be there when work is targeted to begin.

No one can foresee a recession. Or when the monetary tap might start to run dry.

The state Transportation Department gets its funding for construction work through federal funds, dedicated highway-user revenue, a state/federal gasoline tax and vehicle registration fees.

Federal roadway funding to Nevada has remained "relatively stable" at $300 million for the 2011-13 biennium. But Larkin-Thomason said the percentage of state/federal gasoline tax revenue, which supplements Transportation Department construction, has "flat-lined" at approximately $420 million per year from its high of $470 million in 2007. That's because higher gasoline prices result in fewer people driving and people driving fewer miles.

Moreover, communities that would co-op with the Transportation Department on road construction projects because it benefits their residents simply don't have the discretionary finances to chip in.

"They're depleted," Larkin-Thomason said of their resources.

Clark County receives approximately 60 percent of the Transportation Department's state funding, although District 1, being regional, must look beyond the many taillights of Las Vegas Valley vehicles.

As the region grows, so does the need to improve, as well as maintain, roadways throughout Southern Nevada.

In establishing and maintaining a regional master program, the state agency works closely with the Regional Transportation Commission to determine which proposed projects are the most urgent and/or significant.

"It's a challenge, financially," Larkin-Thomason said, although she sees signs of the economy leveling off, which means planned Transportation Department projects will be realized - in time.

"With that in mind, we're taking a very hard look at our program. We're looking at projects that appeared to be high priorities at the top of the (economic) boom and asking, 'Are they still a top priority?'

"We're looking at everything as we do a thorough review of our five-year plan and looking at the opportunity to leverage our program" against the ongoing frailty of the economy.

At the top of the agency's list is maintaining the quality of existing roadways.

From there, it's on to new projects, where everything is taken into consideration - from improving the mobility and connectivity of motorists, to furthering economic development in an area, to enhancing community well-being.

"As you look forward, you look for your needs ... while you also look for your availability of funding," Larkin-Thomason said.

FRAGILE PARTNERSHIPS

Funding for a Transportation Department project, especially the larger ones, generally comes in the form of a partnership including the Regional Transportation Commission, the county and/or benefiting cities, in any and all combinations.

So while the state agency must consider its available federal/state monies, it routinely must check the coffers of its partners to see if they're in a position to proceed as originally planned.

It takes only one partner to be short-funded to put a project on hold.

"As you look to move forward with a project (from its planning), you often have to take a look at the locals - the county or the city or whichever. You have to see if what was originally a stable funding source is still there," Larkin-Thomason said.

"Say a city or agency was originally putting up 50 percent on a project and you're planning to put up 50 percent. If, because of the economy or money that has to be diverted elsewhere, they now don't have the 50 percent to move forward, we can't step up and pick up their 50 percent.

"We're finding that story all over the valley."

Such is the case with the shelved phases for the U.S. 95 northwest corridor expansion project.

When asked about the city of Las Vegas' financial support for the project's Phase 3, which was part of the original plan 12 years ago, spokeswoman Diana Paul replied, "At this time, we are still in discussions with NDOT as to who is responsible for these improvements, so we cannot comment until we've had a chance to meet with NDOT to discuss."

The latter phases of the U.S. 95 expansion is not the only major Transportation Department project being delayed by funding issues. So, too, is the widening of Interstate 15 from four to six lanes between Craig Road and Speedway Boulevard, a project that would cost upward of $140 million.

Still, there are major projects moving forward with the help of Transportation Department funding:

■ The McCarran International Airport connector, where the agency is kicking in approximately $35 million for Clark County's $54 million, five-phase construction.

■ The I-15/Cactus Avenue interchange in the southwest valley, to cost in the $50 million range.

■ The reopening of F Street, which will cost between $13 million and $16 million.

■ The 2.75-mile first phase of the Boulder City bypass for the south-and-west circumvention of driving through the city's downtown, at an expected cost of $170 million to $210 million.

■ The widening of I-15 from Dry Lake to north of the Logandale/Overton interchange, to come in between $40 million and $49 million.

In the end, trying to determine which projects to move forward is not unlike a family on a tight budget during tough economic times trying to decide how to pay its bills - without breaking into the kids' piggy banks.

"Whether it's us or the county or the cities, there's only so much money available," Larkin-Thomason said. "You can't pull the money out of the air."

Contact reporter Joe Hawk at jhawk@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2912. Follow him on Twitter: @RJroadwarrior.