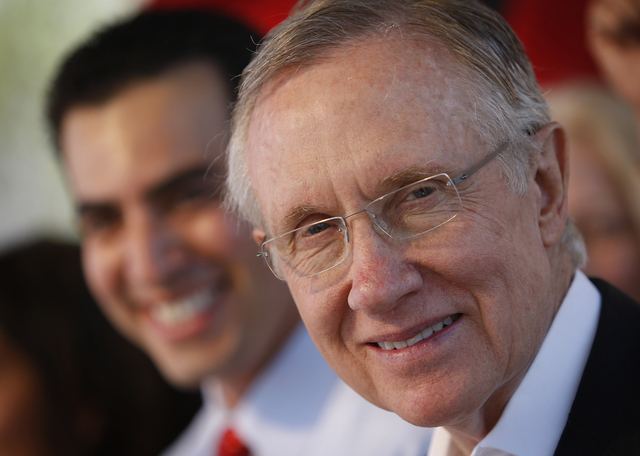

Like him or not, Reid’s rise is the story of Nevada

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

WASHINGTON

The day after he lost an election to become mayor of Las Vegas in 1975, Harry Reid looked in the mirror and saw a 35-year-old has-been.

By his admission he had blown a race for U.S. Senate a year earlier, losing by fewer than 700 votes to Republican Paul Laxalt. Against the advice of his friends, the ambitious young Democrat threw himself into the mayor’s race, “and I got beaten again, and this time it wasn’t very close,” he wrote in his 2008 memoir, “The Good Fight.”

“I assumed that I was finished with political office,” Reid recalled.

Instead, he was just getting started. After serving an appointment as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission and battling the Mob during the tumultuous late 1970s, Reid won an open U.S. House seat in 1982 and, after that, six more House and U.S. Senate races.

In the process, he ascended to become Senate majority leader, making him one of the nation’s top political figures and arguably the most significant in state history.

“In the long run, the 32 years (Reid) has served in Congress make him the most powerful Nevada politician we’ve had in the 150 years we’ve been around,” said Mark Peplowski, a political science professor at the College of Southern Nevada.

FRIEND OF NEVADA WILDERNESS

Reid fingerprints are on millions of dollars Congress has sent back to Nevada for defense, energy, water and transportation. His alliance with President Barack Obama resulted in the scrapping of the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste project. He almost singlehandedly discouraged the construction of new coal-fired power plants in the state while putting Nevada on an alternate path to become an oasis for solar energy with a transmission infrastructure to flow it around the state and beyond.

Reid patronage placed Nevadans and people friendly to Nevada in top energy and natural resource jobs in a federal bureaucracy that has taken actions consistent with his goals.

He has diversified the federal court in Nevada, shepherding the nominations of three women and two African-Americans to the bench. His first African-American nominee, Jonni Rawlinson, later was promoted to appeals judge.

Perhaps most significantly, Reid reshaped the map of modern Nevada and made it greener. His legislation created Great Basin National Park and, decades later, Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area. The 1998 Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act created a template for auctioning off public land and steering the proceeds into state and local coffers and to conservation efforts including the preservation of Lake Tahoe.

Per Reid, few federal land bills for Nevada have been allowed to pass without provisions to increase protected wilderness. There were 64,000 acres of wilderness in Nevada when Reid entered Congress. Today there are 3.37 million acres.

“Without Harry Reid we wouldn’t have much wilderness in Nevada,” said John Hiatt, conservation chairman of the Red Rock Audubon Society.

Roger Scholl, board chairman of Friends of Nevada Wilderness, said Reid once explained his concern about Nevada’s natural features grew in part from seeing a Boy Scout camp at Piute Springs near his childhood home fall victim to litter and neglect.

FROM SEARCHLIGHT TO SENATE

Harry Reid’s backstory has been much recounted.

He was born on Dec. 2, 1939, in a shack built of railroad ties under a tin roof in Searchlight, a rough-and-tumble mining town 55 miles south of Las Vegas, where his father made a living with a pick and shovel and his mother raised four boys. Reid has pointed out by the time he was born the leading industry in Searchlight was no longer mining but prostitution, and his mother took in laundry from the brothels.

Reid attended elementary school in a two-room schoolhouse. For his first two years of high school, he hitchhiked 45 miles to Henderson at the beginning of the week and stayed with relatives while he attended Basic High School. Henderson of the mid-1950s was a working-class town whose breadwinners toiled at the Basic Magnesium plant, the world’s largest refiner of the “miracle metal” that helped the United States win World War II.

By the time he was a high school senior, the young man was a scrapper with a ducktail. He played football and baseball, was chosen student body president, boxed as a middleweight and once got into a fistfight with the disapproving father of his girlfriend, Landra Gould, who later became his wife.

With help from his friend and mentor Mike O’Callaghan, a constant ally who later became governor, Reid obtained a job as a Capitol Hill police officer to work his way through law school at George Washington University. His first job as part-time city attorney in Henderson in 1964 set Reid on a path toward a career in law and eventually politics.

Harry Reid’s rise from hardscrabble could only have been possible in Nevada and perhaps a few other Western states, according to historians.

In relatively young Nevada, there was no entrenched power structure to deny opportunities to young up-and-comers. The same factors fueled the advancement of Reid forebearers Laxalt and Pat McCarran, the sons of Northern Nevada sheep herders who became senators rivaling Reid in the Nevada pantheon.

“It’s certainly the case with Nevada that there are possibilities for social mobility that don’t exist in older, more established areas,” said Michael Green, associate professor of history at UNLV.

In politics, “Nevada is the open arena, where anybody can step through the ropes and take a lick or give it,” Peplowski said. In a larger state, Reid “would have been lost.”

THE RESIDUE OF DESIGN

Reid, 74, is up for re-election again in 2016, and he says he intends to run. Bold moves throughout his career and a manner that charitably has been described as far from charismatic have fueled his opponents. His belief that government does good — a philosophy dating to his New Deal upbringing — rubs wrong with many Nevadans who want less government these days.

Reid’s job as majority leader to support an unpopular Obama, bash Republicans in a hyper-partisan Congress and lead a Democratic caucus whose members generally are more liberal than he is has further inflamed critics, emboldening the right and increasing his vulnerability.

But Reid has built a formidable political machine, marshalling support among Democratic loyalists, powerful casino and industry leaders who recognize his clout, unions in Las Vegas and Reno and the growing-potent Hispanic community.

Reid has shrugged off talk about his standing or possible legacy.

“I’m just going to continue doing my job,” he said in November 2012, when he became the longest-serving Senate majority leader since Sen. Mike Mansfield, D-Mont., in the 1960s and 1970s.

In “The Good Fight,” Reid said his arrival in Washington “was the culmination of all else that I had done in my life, and brought me to what I have come to think as my life’s work, work that is ongoing.”

Green, the UNLV professor, said Reid’s story is the story of Nevada.

“Branch Rickey used to say luck is the residue of design,” he said of the Brooklyn Dodger general manager who made Jackie Robinson the first black player in the major leagues. “You make your breaks. Yes, Reid had a lot of help. But he’s made his breaks, and that fits into a Nevada theme.

“People historically have come here in pursuit of wealth, whether through mining or at the tables,” Green said. “Luck has a lot to do with it. But so does hard work and effort, and Reid fits into that story. You don’t have to love him or like him to acknowledge these things.”

Contact Steve Tetreault at stetreault@stephensmedia.com or 202-783-1760. Find him on Twitter: @STetreaultDC.