Macabre duties all in a day’s work for Nye County official

PAHRUMP — Some death scenes stay with Ginger Stumne, disturbing her sleep.

Like the man found a year after his suicide, a troubled soul reduced to bones hanging from a rope. Some of the dead she knew in life, like the close family friend she found in bed, his once-vital body withered, already gone for weeks in the middle of summer. She only recognized him from the photo on his driver’s license.

“That one,” she says, “gave me nightmares.”

Stumne isn’t a homicide detective or medical examiner; they collect a government checks for their labors. But not Stumne.

She’s Nye County’s public administrator, filling an elected position for which there is no budget — a baffling fact considering her macabre duties. Because the county has no coroner, Stumne must appear at the scene of each unattended death (one where no family member is present) across this vast but underpopulated county — the nation’s second-largest at 18,000 square miles, home to just 43,000 residents.

While she’s not there to collect evidence or discern cause of death, her role still looms large. Because when people die without wills, they leave behind a financial and emotional quagmire for their grieving families.

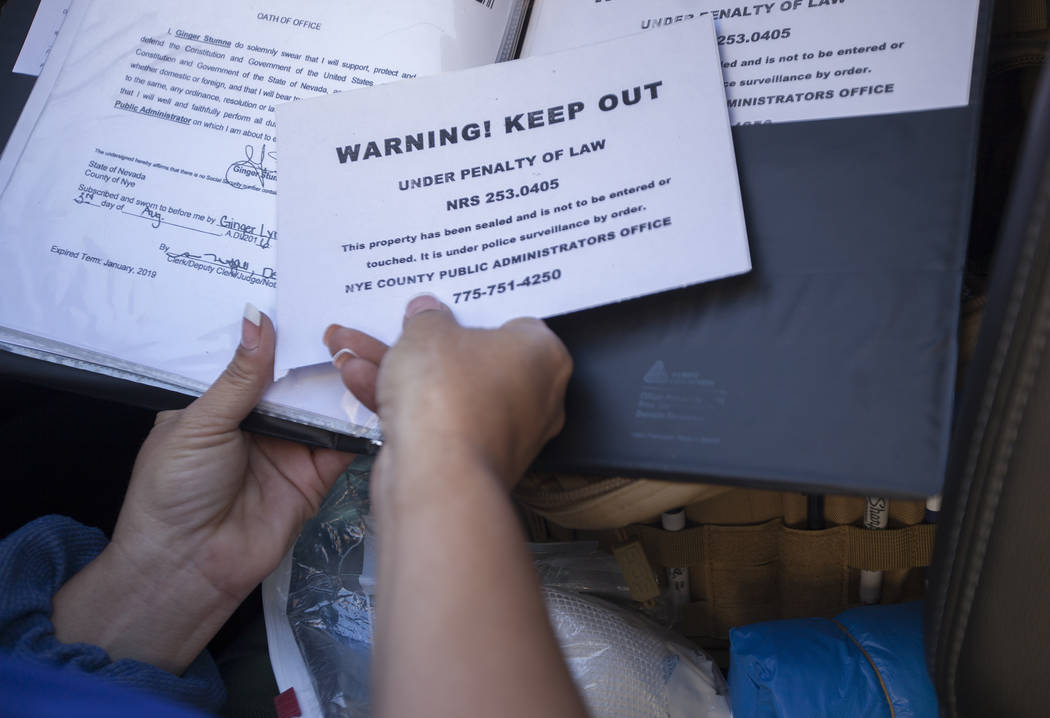

That’s where Stumne excels. The 45-year-old grandmother protects all assets until family members arrive to claim them. At death houses, she and her volunteers pull the blinds, unplug the toaster and electrical appliances, secure the car keys and resolve the fates of pet dogs, cats, birds, a squirrel and, once, even a snake.

She’s a fixer, social worker, consigliere, financial adviser and family hand-holder.

And a custodian. Her staff is also responsible for cleaning up the death scene, even after suicides. They walk into homes wearing gloves, booties and masks, and sometimes hazmat suits because of the blood and risk of infection.

She pays for everything out of her own pocket, shelling out for death certificates, cremation and burial fees, electric and water bills for the estate, even gas for her truck.

Because she draws no salary from Nye County, Stumne must rely on money she makes from a small percentage she earns from the estates she handles.

And those can be few and far between and not be worth much, so her salary each year varies wildly.

Once an estate is settled, Stumne receives a percentage, after scrutiny by a county judge. But many cases drag on for years, and there is no guarantee that she will ever collect a dime.

In 2016, for example, she made $8,000, but last year she made a more respectable $52,000.

Nye County Sheriff Sharon Wehrly said she is amazed at the quality of work Stumne performs and thinks she should be paid by the government.

“I’ve been around a very long time and I’ve seen a lot of people do this job; some did it well and others took advantage of the position,” she said. “Ginger has taken this job and turned the office around. She’s done an admirable job and I’d really like to see her continue.”

Wehrly said she thinks Stumne should be paid through the District Attorney’s office but that despite recent conversations about the issue, that has yet to happen.

“It really needs to be a paid job,” she said.

Inside Stumne’s makeshift trailer-turned-office, grease boards detail the 40-odd ongoing cases and $4,000 in fees and expenses that remain uncompensated. In a storage closet, she keeps the cremated remains of those deceased and still unclaimed. Inside a safe kept closed with duct tape — there’s no money to fix it — she keeps weapons used in suicides.

One one wall, Stumne also keeps a placard, a gift from a family, that reads, “Be Fearless.”

“Because you’re dealing with death and an often-angry public,” she says.

Stumne responds around the clock to deaths that occur hundreds of miles away. She conducts nationwide — and even international — searches to locate the family members of those who die on her watch.

“I know if my mother died, I wouldn’t want (anyone) to learn about it on Facebook or TV,” she said. “I want to let them know the deceased’s home and estate are secure until they get here, and not be bombarded with what-ifs.”

The job can age you. Stumne has encountered family who want nothing to do with the deceased. Like the man who said of a brother who took his own life, “Good, I’m glad he’s dead. But if I have any money coming, you better get it to me fast.”

In training seminars, would-be volunteers walk out after seeing photos of death scenes, saying, “Whoa! I’m not up for this!” before even encountering their first body. Many nights, after tending to the indelicate details of death, she removes her clothes in the garage, deciding whether to toss them in the washer or throw them away.

Sometimes, her boyfriend does a sniff test before he even opens the door.

But Stumne carries on. A compact woman with dirty-blond hair, she dresses in blue jeans and wears an oversized smartphone on her belt like a gun in a holster. As for guns, she has one of those, too. She recently bought a 9 mm handgun as protection against a public that both misunderstands and threatens her work.

Over the years, the Nye County public administrator’s office has been rife with bad luck and bad press. Twenty years ago, Public Administrator Robert “Red” Dyer and his wife, Jennette, were charged with siphoning money and goods from county residents whose estates they were responsible for administering.

In 2010, Robert Jones resigned from his public administrator’s position after he was tied up and robbed at gunpoint by assailants who targeted him because they knew he handled valuables as part of his job.

When Robin Dorand-Rudolf suddenly resigned in 2016, Stumne — then a public administrator’s volunteer assistant — took over to complete her four-year term.

The move has put her in the public’s crosshairs.

Not long ago, after she bought her dream vehicle — a “white Ford diesel jacked-up pickup truck” — Stumne was confronted by a man in a newer-model Mustang. “You stole that truck,” he shouted at Stumne. “You can’t afford that truck.”

Neighbors call the police when she arrives to remove items from a house. Then there are friends and roommates who don’t like the fact that without a will, the estate of any deceased legally goes to family — even if the person had little contact with relatives or had talked about doing something else with his or her money.

Two roommates with criminal records have left Stumne threatening voicemails. “I can’t believe you can sleep at night,” one began. “We’re coming after you.”

Her response was pure Stumne: She told them to have their attorney call her. Her job was to follow the law. Still, the threats give her pause.

“I’m the bad guy,” she says. “They know what I drive.”

Such chutzpah represents a remarkable turnaround for a mother of three who was once physically abused by two former husbands, who at age 40 found herself unemployed, undereducated and struggling to provide for three teenage children.

Raised in Pahrump, Stumne began running a family-owned local gym at the end of her first abusive marriage. When her parents sold the business, Stumne was out of a job. Back then, she didn’t even know how to apply for unemployment insurance.

But she learned.

She harnessed a compassion to help others and threw herself into a public-service life.

While working marketing jobs for a law office and senior center, she volunteered as a sheriff’s dispatcher, and opened a licensed day care center and later a nonprofit that advocated for senior citizens, U.S. veterans and the disabled. She volunteered at a hospice center and became a court-appointed advocate for children. She also became a legal guardian to a physically and mentally disabled couple brought to Pahrump after being abused in a California mental hospital.

All the while, she received her paralegal certificate via an online course and continues to take pre-law classes with the goal of becoming a probate lawyer. This semester, she once again made the dean’s list.

All this from a mother who once had to tell her children she was too busy to stop at a McDonald’s when in reality she was too poor to afford a burger and fries.

“I want to show my kids that as long as you want to improve yourself, your age does not matter,” she said. “You can do it. Because there are more than just eight hours in a day.”

In 2016, when Stumne stepped up to lead the troubled public administrator’s office after her boss resigned, her family worried she was going to ruin their good name.

Stumne disagreed. “I told them I wasn’t going to ruin it, but I was going to take our good family name and clean up this office.”

One California woman witnessed Stumne’s style firsthand when she handled the death of an older brother and thanked her in a card that hangs on the wall. It cites Stumne for “taking the pressure off us and I was able to focus on grieving the loss of such a fine man that was my brother.”

With her own children now grown, Stumne is helping raise her boyfriend’s two teenage boys. He’s helped her redefine her self-image and reclaim the self-worth taken from her from two abusive marriages.

His message: It’s OK to have your own life and not work around the clock.

But for Stumne, slowing down takes work. While she pursues her legal degree, she plans to run for re-election next year.

“I have to keep busy,” she says. “That’s who I am.”