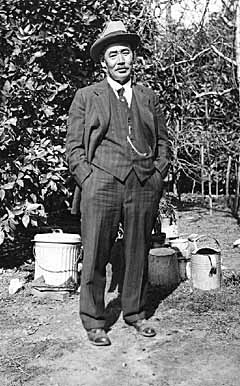

Bill Tomiyasu

He wasn't an engineer or a construction worker, but Yonema "Bill" Tomiyasu just as surely helped build Hoover Dam.

He was a local farmer who fed the dam's workers with the literal fruits, and vegetables, of his labor: fresh tomatoes, asparagus, luscious watermelons and canteloupe.

All were items of produce that, prior to Tomiyasu's innovative farming techniques, mostly had to be shipped to Las Vegas from elsewhere, at added expense.

A Japanese-born immigrant who planted roots in Southern Nevada in 1914, Tomiyasu was one of the first Asian Americans to settle here.

He arrived with the specific intention of owning and operating a ranch -- which people of Japanese origin were not permitted to do, at the time, in neighboring California, where Tomiyasu had been living.

He went on to help his adopted country fight his land of birth during World War II, delivering produce and poultry to the mess hall of the airplane gunnery school near Las Vegas, which is today Nellis Air Force Base.

Then the Las Vegas Valley began to urbanize. The Indian labor that Tomiyasu used to hire for ranch hands became scarce. Gradually he switched from agriculture to raising landscape plants.

Bill Tomiyasu's son, Nanyu, 80, today is completing the final contracts for the family's horticulture business as he readies for retirement. His own grown sons have declined to follow him in the back-breaking occupation.

So, the Tomiyasu business dynasty is ending. But signs of a Tomiyasu legacy remain.

A street, Tomiyasu Lane, still runs where the family ranch used to lie, though the land itself -- in southeast Las Vegas, near the intersection of Pecos and Sunset roads -- is broken up into many private upper-crust estates, just south of Wayne Newton's property.

A public building also bears the family name -- the Bill Y. Tomiyasu Elementary School at 5445 Annie Oakley Drive. And throughout the valley, trees continue to prosper that were germinated and raised to saplings by Tomiyasu.

Nanyu Tomiyasu recounts the story his dad personally told of the exodus from Japan to California, and then to Las Vegas.

Yonema was born near Nagasaki, Japan, the son of a sugar cane farmer who also raised chickens. There he learned the skills that would carry him through life.

But times were hard for the Japanese peasant class. Nanyu recalls that his father's family could hardly ever afford to eat any of the eggs their hens laid. So, Yonema vowed to become affluent one day. "He said, 'One thing's a must for me. I'm going to have six eggs a day.' And he did," Nanyu says.

In 1898, at age 16, Yonema left Japan for the United States to "have a look-see," as Nanyu puts it. He landed in British Columbia, Canada, then made his way to California, near San Jose, where a sister was already living. He made ends meet by picking fruit.

But "he gradually drifted on down toward Fresno, Santa Barbara," taking jobs in gardening and plant nursery work, Nanyu says. By 1910, Yonema -- still single -- was living in San Bernardino. He had hired on at an Elks Club as a groundskeeper, but eventually transferred to the kitchen and became head cook.

"An Elks member who was a real estate agent ... came up to Las Vegas to sell lots," Nanyu continues. On his return, the agent, M.M. Riley, "walked in the kitchen and told my dad, 'You'd better go to Las Vegas.

" `There's lots of water, lots of land up there. It's hot, and gets fairly cold (in winter). But if you can stand the weather conditions, you can make a living up there.' "

Nanyu took the advice. Soon, on April 25, 1914, The Las Vegas Age newspaper reported, "B.Y. Tomiyasu, secretary of the Japanese Association of San Bernardino, Cal., has been in Vegas the past week making arrangements to begin work on the 40 acres on Winterwood Boulevard recently purchased by him."

In 1916, Yonema permanently moved to Las Vegas. In 1917, he married. "It was an arranged marriage, what they call a 'picture' marriage," says Nanyu, referring to the practice of agreeing to wed on the basis of a matchmaker's recommendation and exchange of letters between prospective spouses, which usually included photo portraits.

Yonema's bride, Toyono, came from urban Sendai, Japan, to desolate Southern Nevada. Data from the 1920 Census measured the entire Las Vegas population at 2,304. That year, the county recorded 62 residents of Japanese extraction. "She told me, when I was 6 or 7, her first couple years were really scary. She'd never heard a coyote howl," recalls Nanyu, their oldest son, born in 1918.

But farming in Southern Nevada wasn't as simple as reproducing the methods Yonema had used in Japan or California.

In his early years of experimentation with food crops, Tomiyasu depended on alfalfa as his money crop.

"He got seed catalogs from Los Angeles and got all their planting guides. And they were absolutely worthless here," says Nanyu. "He said, 'OK, I'm going to plant all these crops every two or three weeks, and find the best schedule.' "

After five or six years, he had succeeded in developing planting timetables for a cornucopia of produce: onions, green onions, carrots, radishes, beets, cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, endive, bell peppers, melons.

The local press sang his praises.

"Las Vegas beats the world!" begins one article on the front page of the Feb. 14, 1930, Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal. "Bill Tomiyasu, better known in the city of Las Vegas as Bill Jap, has a cutting of asparagus, home grown, that is at least two weeks ahead of the California market. And by the time California asparagus is on the market, Bill Jap will have his all sold."

In his "From Where I Sit" column in the June 28, 1930, Evening Review-Journal co-owner Al Cahlan mentioned Tomiyasu's efforts to cultivate the Colorado River bottomlands. "It seems like about the time you get disgusted trying to find a good melon in the shipments from other climes, the home-grown melons land in town, and the search is over ...

"Bill Tomiyasu and Fred Haganuma (also of Japanese descent) are pioneering the game down on the river bank, near Searchlight, building each year, and bring new raw acreage into production.

"They are demonstrating just what can be done under the influence of this remarkable Clark County climate, with water on the desert lands."

During Nanyu's childhood years, the family -- which had grown to include three more siblings -- spent most of its time working the fields. "We supplied restaurants" in Beatty, Jean, Goodsprings and Sloan, Nanyu recalls.

The children and their mother helped Tomiyasu harvest, clean and bundle the produce. Regularly, Nanyu went with his father on his delivery rounds, bouncing along dirt roads in a heavily laden family truck.

In the 1930s Tomiyasu struck a great coup for the family business, landing a long-term contract with the Six Companies -- a consortium of companies which was building Hoover Dam -- to supply food to their construction camp mess halls.

Before World War II, Japanese truck farmers in the West had already distinguished themselves as hard-working.

"Issei (Japanese-born) men and women farmed side by side, often paid higher rents, and sustained their families on smaller profit margins," Andrew B. Russell wrote in his 1996 master's thesis for UNLV. His thesis is titled "Friends, Neighbors, Foes and Invaders: Conflicting Images and Experiences of Japanese Americans in Wartime Nevada."

In California, the Japanese knack for agriculture aroused ethnic-based resentment on the part of what Russell calls "whites attempting to break into the farming 'aristocracy' ... California growers at first recruited large numbers of Japanese as farm laborers but turned suspicious of the Issei when they put their outstanding talent for horticulture to their own uses."

Anti-Japanese bias in California, Oregon and Washington culminated in the forced relocation of Japanese to internment camps during World War II. Such bias wasn't so evident in prewar Southern Nevada.

In the decades before the war, Nanyu and his siblings attended a one-room elementary school in the Paradise Valley School District.

"It was one of the most integrated schools I've ever been to," says Nanyu. In addition to the four Tomiyasu children, its enrollment included a Japanese-American cousin, the six children of a white Mormon family and the child of a black rancher. Later, the Tomiyasus were assigned to a downtown Las Vegas grammar school when several districts consolidated.

In Las Vegas at large, "Socially, we weren't integrated. But as far as gaining respect of the community for what he did, my father got that," Nanyu says.

Russell theorizes in his thesis that the earliest Japanese in Clark County -- who arrived soon after the first Las Vegas lots were sold in 1905 -- were able to keep a low profile. They did not earn unwanted prejudicial attention because most had a language barrier, worked solely for the railroad and lived together in a compound.

"Within the compound, any cultural activities would not have been apparent to outsiders," Russell writes.

As World War II loomed, though, anti-Japanese sentiment kept on building in California, with some spillover to Nevada.

"Nevada's preoccupation with these immigrants was a reaction to California's more successful efforts at restricting the Japanese. These, it was feared, might cause a great influx of Japanese into Nevada," writes Russell in another article, about the Japanese in Nevada from 1905 to 1945, which was published in the spring 1988 Nevada Historical Society Quarterly.

But the forecast never materialized for Southern Nevada. The Census for 1940 showed 49 residents of Japanese race in Clark County, compared to a total Las Vegas population of 8,422 residents.

Anti-Japanese events did occur sporadically during that four-decade span in certain Nevada communities -- such as Reno and Fallon -- but none occurred in the southern part of the state, perhaps because of the low percentage of Japanese in the overall population.

Yet the federal war agenda did affect Nevadans.

No internment camps were located in Nevada. Nor were Nevadans of Japanese descent interned into camps, except for a few suspected of unionizing activity in the mining and rail towns of Ruth and McGill in White Pine County. But hundreds of workers there did petition to have Japanese employees fired, and by mid-1942 most Japanese-Americans had moved away from those two towns.

Even upstanding Japanese Nevadans were kept under surveillance to a certain extent. Throughout the state, Japanese followed federal policy by turning in short-wave parts from their radios, cameras and even flashlights. Several of the Tomiyasu children, who were in college in California, stopped their studies and returned home.

In Clark County, Sheriff Gene Ward -- whom Nanyu remembers as a family friend -- "staunchly defended the Japanese farm families of the area," reports Russell. "One Las Vegas Issei was interned ... But that action came only after this individual had publicly aired his sympathy for Japan through letters to the local newspaper," Russell writes in "Friends, Neighbors, Foes and Invaders."

Nanyu Tomiyasu was instructed by the government -- as were many sons of white farmers -- to stay and help his father on the ranch, to maximize its output during the war years.

At one point in the war, Nanyu says he and his brother, Kiyo, received special dispensation from the FBI to drive across Hoover Dam, classified as a military target from which Japanese were to be restricted. The two then followed a route, also prescribed by the FBI, to pick up a Japanese-American family friend who was being released from an internment camp in Poston, Ariz.

The friend, Seiji Iyemura, had been Tomiyasu's helper at the Elks Club in San Bernardino, and spent the rest of the war working at the Tomiyasu ranch. "He was able to track when he came to the United States, where he worked, where they worked together. My father vouched for him," Nanyu says.

The elder Tomiyasu was not embittered by the U.S. wartime treatment of Japanese, not even the internment, according to Nanyu. His father's attitude was, "That's fate. There's nothing you can do about it."

After the war Tomiyasu prospered, until the 1960s, when he obtained a loan to expand his nursery operations.

The way Nanyu remembers it, a member of their church invited them to take the loan. In an ensuing lawsuit, the Tomiyasus claimed that someone fraudulently obscured the repayment terms in such a way that the Tomiyasu family ended up delinquent.

In a controversial foreclosure that made Las Vegas headlines and went to the state's Supreme Court, Tomiyasu lost the entire 100-acre ranch -- valued then at $240,000 and today some of the most valuable land in Paradise Valley -- over an $18,000, second-trust deed.

The Supreme Court ruled 2-1 for the purchasers of the foreclosed property. The dissenter was District John Gabrielli of Reno, who heard the case in place of Justice Frank McNamee, who was ill. Gabrielli wrote in his dissent, "The conscience of this writer is shocked that in this age, an 82-year-old Japanese resident of this state since 1916 and his family can be treated with such injustice."

The family was evicted, but resumed nursery operations at another location. Yonema Tomiyasu died in 1969 at the age of 87.

But his legacy lives on, in several ways.

With dry wit, Nanyu jokes that allergy sufferers can thank his father for the abundance of fruitless mulberry trees that dot the Las Vegas landscape -- and dust it every spring with their pollens.

Forty years ago, Tomiyasu had popularized the trees, which came from Modesto, Calif., growers, who were more concerned with developing a fruitless tree than one that was non- pollinating.

But also, whenever a homeowner today picks up a brochure on desert gardening from the Clark County Extension Service, he is reaping the benefit of Tomiyasu's painstaking research on optimal planting schedules and desert-tolerant plant varieties.

"He did all the testing," confirms Linn Mills, a horticulturist for the Las Vegas Valley Water District.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full