DAD’S IMAGES OF DEATH

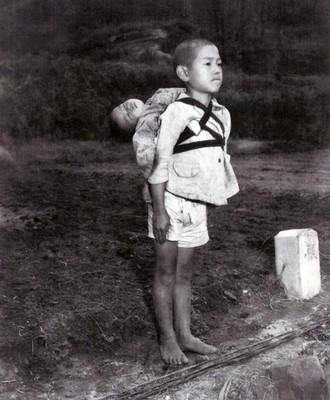

The photograph of a Japanese boy standing at attention with a child strapped to his back lay on the kitchen table.

Tyge O'Donnell, then a college student, stared at the photo, suggesting to his father, Joe, that the infant hanging out of the makeshift baby carrier "looked sound asleep."

"No, son, he's not sleeping," O'Donnell recalls his father saying. "The little boy is dead."

O'Donnell, now a 37-year-old bellman at Caesars Palace, had grown up knowing his father primarily as a photographer for the White House and Marine Corps, but it wasn't until that moment in 1989 when he found out how closely his dad had chronicled the devastation wrought by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"I came into the house from my summer job at a hobby shop and there were these photos on the kitchen table," Tyge O'Donnell said. "I had no idea he had seen all that."

Also on the table were pictures of the newly orphaned and badly burned wandering in the rubble. But O'Donnell said it was the photo of the brothers that awakened a memory so powerful in his dad, he seemed to see the image play out before him.

"He told me that the boy dropped his brother off at a crematory and watched him burn," O'Donnell said. "The boy bit his lip so hard it bled. My dad said he wanted to comfort the boy, but he was afraid if he did they would both break down."

Hiroshima was bombed 62 years ago today on Aug. 6, 1945. Three days later, Nagasaki was the target. More than 250,000 died in the two World War II American missions that all but obliterated two of Japan's major cities.

To commemorate the anniversaries, Tyge O'Donnell has just finished preparing a Web site, www.myspace.com/thephoenixventure, dedicated to his father's work. More than 40 of his father's photographs from Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be seen. On Thursday O'Donnell stood in his condominium near the Strip and put the finishing touches on the Web site.

"My father wanted me to make sure that I continued to share his photographs so we can do everything possible to stop nuclear war from occurring in the future."

Joe O'Donnell, 85 and in a rehabilitation hospital in Nashville, Tenn., can no longer talk about his experiences.

"He had a stroke and it is very hard for him to communicate," his wife, Kimiko, said in a telephone call from her Tennessee home.

The elder O'Donnell was a White House photographer during the administrations of presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon.

After the war's end in 1945, the military had dispatched him to the Japanese island of Kyushu to photograph the landing of American occupation forces. But within three weeks of the bombings, he was sent to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where he would spend the next six months taking pictures of the devastation.

At first he used a Jeep to get around. But he ended up trading cigarettes for a horse because it would take him places the Jeep wouldn't go.

He sent one set of photos back to Washington, D.C., but always kept copies for his personal collection.

After returning to the states, he kept the negatives of his personal pictures in trunks in the attic. He gave instructions to his family never to touch the trunks, and that's where they stayed for 45 years.

"He told me the reason he didn't get the photos out is that he wanted to forget what he saw," Tyge O'Donnell said.

For a while he did forget.

But in 1989, Joe O'Donnell, suffering from depression not only from the memories but from recurring health problems, went on a religious retreat at the Sisters of Loretto Motherhouse in Kentucky.

"My dad said he often wondered why he had been spared when so many others were killed," Tyge O'Donnell said. "On the retreat he saw this sculpture of a man created in honor of the victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. He decided that this meant he was spared to use his experiences to prevent nuclear war."

He came home to Nashville and pulled the negatives and photos out of the attic, deciding that he would put a traveling photo exhibit and book together. He had a purpose, but at a cost.

Working on the project actually caused his depression to deepen, his ex-wife, Ellen, said recently.

Tyge and a neighbor helped with captions for pictures for both an exhibit and the book. Joe O'Donnell decided not to use the most gruesome pictures, including faces ripped off and charring burns.

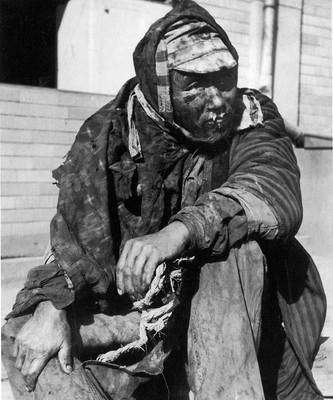

A survivor of the Nagasaki blast sat on the steps of a building turned into a hospital. The man said he wore heavy clothes to protect his badly burned flesh from the sun. Holding his only possession, a piece of rope, the man said doctors used mercurochrome and cucumber slices to treat his burns.

Tyge recalled how his father described his trip to Nagasaki, where maggots were everywhere, and where children were so hungry they ate apples full of flies.

"My dad said the smell of the dead was so bad that he almost didn't want to breathe," Tyge O'Donnell said.

Joe O'Donnell published his first book in Japan in 1995 for the 50th anniversary of the bombings. Titled "Japan 1945, Images From the Trunk," it was widely read in Japan, where news media often made him the subject of stories.

In the Far East for the anniversary, the elder O'Donnell told the Japanese that he wanted to express his "sorrow and regret for the pain and suffering caused by the cruel and unnecessary atomic bombing of your cities. I believe it was wrong, morally wrong, just as wrong as the Holocaust. ... We owe it to those that died, to keep their memory alive."

His statement, which called for no more Hiroshimas or Pearl Harbors, was widely circulated throughout Japan.

"Some Americans, of course, have said they don't like positions like my father's and they have said so," Tyge O'Donnell said.

In 2005, the Vanderbilt University Press published O'Donnell's "Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine's Photographs from Ground Zero." It was based largely on the same photo collection.

Also that year, Joe O'Donnell wrote an article for American Heritage magazine explaining what happened after his experience in Japan: "Years later, many years later, the nightmares began: the voices of the children, the endless stretches of rubble and bone, the stench. Over and over again. The voices were always pitiful, always begging. Yet they were accusing, too."

Though both O'Donnells believe the war would have ended quickly without the use of the A-bomb, Gen. Paul Tibbets, the Enola Gay pilot who flew the mission over Hiroshima, characterizes that viewpoint as "revisionist history."

"We saved hundreds of thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of Japanese lives by using those bombs," Tibbets said in an interview with the Review-Journal in 2005. "An invasion of Japan would have been incredibly costly for everybody."

Tyge O'Donnell said, though, his father wants people, especially schoolchildren, to learn from the photographs and the Web site.

"The fight my dad wants to fight is the fight for real peace. And you don't get that by killing people."