Clark County school organizational teams absorb the deficit news

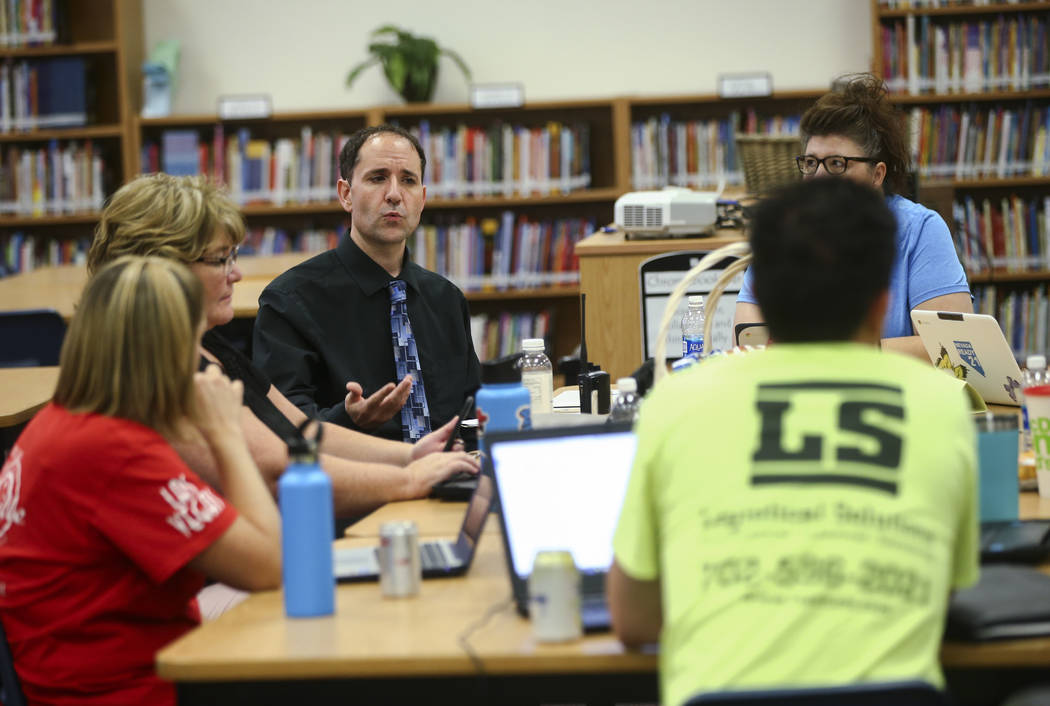

Saville Middle School Principal Sean Davis delivered the bad news to his school organizational team first.

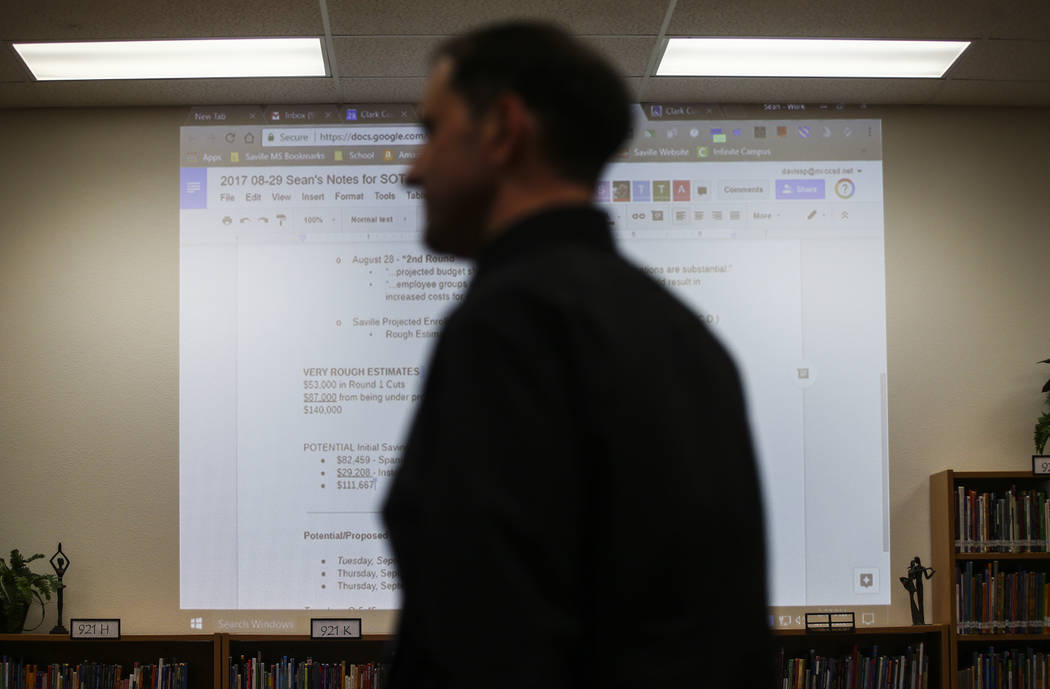

The school will have to pay for several years of raises for its administrators as the Clark County School District grapples with a budget shortfall. The projected impact to Saville, just from its administrative raises: $53,000.

Then came a bit of better news: a Spanish teacher left over summer, and Saville could save money by not filling that position, he told the team Tuesday. Instead, students could take the class online.

But wait: A projection that Saville would have fewer students than anticipated could cost the school another $87,000. Even with the elimination of another instructional assistant job, Davis said, the school would only have cut $111,667 of the estimated $140,000 shortfall it needs to eliminate. And that’s likely not the end of it.

“The problem is we have round two (of cuts) coming,” Davis told his team, “because again the shortfall is expected to be much worse.”

The concern evident at the Saville meeting is spreading to schools throughout the district, which is coping with an estimated deficit of $50 million to $60 million.

“This info came out along with some rumors,” Davis said of the deficit. “It’s always a dangerous thing when you have rumors going around.”

Eye-opening insiders’ view

In the first full year of the new school-empowerment model, the financial woes have immediately plunged principals and their school organizational teams into the weeds of educational financing. For the first time, parents, support staff and teachers are seeing how the budget process unfolds, and what happens when there’s not enough money.

The immediate task before them: Collectively trim $17 million from their individual budgets. And that amount could increase, as the district finalizes its finances for last fiscal year, possibly swelling to $70 million to $80 million in cuts, according to district Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky.

But with news of the budget crisis, there is a revived call — a local awakening — to the state of education funding in Nevada.

“It’s not a secret that you all are well aware that we’re underfunded,” Valley High School Principal Ramona Esparza told her school team the next day. “Education is underfunded in the state of Nevada. So that’s going to be our fight.”

Esparza said she was thankful at least for the $3.2 million in Victory funding — money targeted for schools with a high percentage of students in poverty — that could free up other money to cover her school’s shortfall.

“We don’t know what will happen in this deficit,” she said. “There’s definite cuts that are coming down, and it’s in every aspect of the district.”

To cut its losses in the meantime, Valley High is tightening the strings in its operational budget.

“When departments are saying, I want to purchase this and I want to do that, I’m saying we have to wait,” Esparza said. “We have to wait.”

Who’s to blame?

It’s unclear what steps the district could have taken, if any, to avoid this shortfall.

District officials have said it sprang in part from lower-than-projected revenues from the state. That includes $14 million less received for kindergarten funding compared to the previous year, and $7 million less from the state’s special education contingency fund, both last year and this year.

The district’s anticipated per-pupil funding level from the state was also $26 higher than the actual $5,700 amount.

State Superintendent Steve Canavero says that’s not the state’s fault, but the result of an optimistic budgeting philosophy.

“Because your boss didn’t give you the raise that you didn’t deserve, doesn’t mean you got your salary cut,” he said.

Canavero argued that the district budgeted those special education and kindergarten funds based on its proportion of the state’s students, and not on specific demonstrated needs. Per-pupil amounts shared by the state were in draft form, he said, and not final.

The state reviews applications that districts submit to the special education contingency fund. Canavero’s team reveiwed Clark County’s applications, he said, and approved those that aligned with the “legislative intent” of the fund — which is to cover certain high-cost special education students.

“We allocate based on applications, and so Clark flooded us with a bunch of applications,” he said. “The team reviewed those with legislative intent and approved a few of them.”

A similar process unfolded with the kindergarten fund, which doles out funds on a case-by-case basis in response to applications that districts submit.

“It is a safety valve,” Canavero said. “You would never budget on a proportional share on either of those two funds.”

Funding formula questioned

Skorkowsky sees things differently.

“We have over 74 percent of the students in the state of Nevada in the Clark County School District,” he said. “So it’s extremely unfortunate to think that the Southern Nevada money that is collected here is not coming back to Southern Nevada, where it is expected.”

He also said the district calculated the per-pupil amount based on information received from the state Department of Education.

“When we have to, by law, submit a budget in April that includes a per-pupil amount. I don’t know how you do that without having conversations with the state department to determine what the estimate is,” Skorkowsky said.

Former Interim Chief Financial Officer Eva White, who oversaw the budgeting process, said she argued for the extra $14 million in kindergarten funding.

“Maybe the thing that wasn’t planned for was, what if we don’t get it?” said White, who left the district in August for a job in Minnesota.

But like Skorkowsky, trustees and perhaps the newly minted school teams across the district, White feels that Clark County is being shortchanged by the state.

“I do not believe Clark County gets the share that it needs of the state funds for the needs that we have in the county,” White said.

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

Memo to Central Services (8-24) by Las Vegas Review-Journal on Scribd

Budget Shortfall Memo (8-28) by Las Vegas Review-Journal on Scribd

Central Services Budget Update Memo (8-30) by Las Vegas Review-Journal on Scribd

What's next?

— Sept. 1: Survey asks community for input on additional budget cuts (closes Sept. 10).

— Sept. 11: District central services provides additional budget cut ideas to address remaining shortfall.

— Sept. 14: School Board votes on additional proposed cuts.

— Sept. 18: Strategic budgets are released to schools. School teams will make revised budgets, factoring in administrative raises and other cuts.

— Sept. 22: Schools submit revised strategic budgets.

— Sept-Oct.: District determines if layoffs are needed.