Retiring UNLV professor’s contributions to the study of Southern Nevada will be long-remembered

When UNLV history Professor Gene Moehring packed his bags in 1976 and left New York for a new job in Las Vegas, he traded a highly developed urban and financial center for a place where history was very much a work in progress.

“We recruited Gene to be our first historian of urban America and urban development,” said Andy Fry, his former colleague. “We laughed that we couldn’t have gotten a more appropriate person. He grew up playing stickball on the streets of Queens, but came here and really embraced Las Vegas as an emerging urban place.”

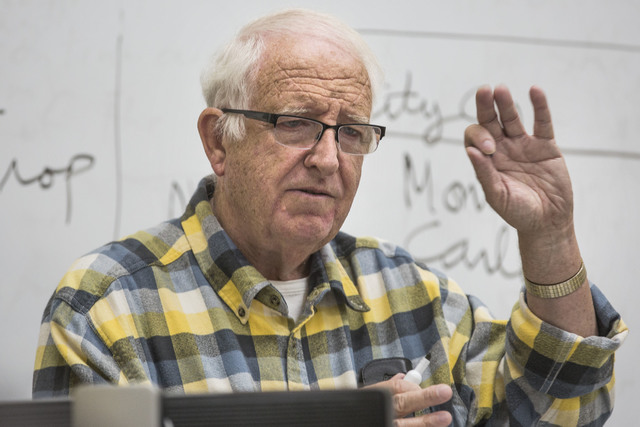

On a recent Wednesday afternoon during one of his final classes in the Flora Dungan Humanities building on UNLV’s campus — just weeks before his retirement on Dec. 31 — Moehring, 69, recalled a moment that seemed symbolic of the rapidly changing city of the time: a crash of three taxicabs in front of the soon-to-be-opened Mirage Hotel and Casino in 1989.

“I remember the first night they set off the volcano — they were just testing it,” Moehring recalled. “And three cabs crashed right in front of it. Nobody had seen a volcano in the middle of the Las Vegas desert before.”

But Steve Wynn’s Mirage was more than just surprising, he said. Moehring calls the subsequent building boom of themed hotels and casinos the “Mirage Revolution” and credits it with reinventing the Strip as a sort of Disneyland for adults.

Dressed in a yellow-and-black checkered shirt and black slacks, Moehring used the incident to illustrate for the roughly 30 students in attendance how the building boom created jobs, which led to a population surge, and then to the growth of master-planned communities and construction of the 215 Beltway.

He spoke methodically, traces of his New York accent still discernible, his knowledge of Southern Nevada history flowing like a stream.

“I really enjoy teaching Las Vegas history,” Moehring said after class. “I came here as an urban historian, interested in infrastructure and how it accommodates growth. I came to a place that grew tremendously — 300,000 people when I came in 1976, now we’re at 2.3 million.”

His ability to make history current and interesting to others made him a favorite with students.

“I had him for four classes,” said UNLV colleague and former student Michael Green, who also teaches history. “And he was one of the first people I took after, after I started moving toward the idea of making this a career. He influenced what I do in the classroom and how I do it. He had and still has fun teaching. He’s not retiring because he doesn’t enjoy it anymore.”

SPOTLIGHT ON THE WEST

Moehring’s first scholarly work, “Public Works and the Patterns of Urban Real Estate Growth in Manhattan, 1835-1894,” focused on the Big Apple, but his subsequent writings shined a spotlight on the West.

When he came to Last Vegas 40 years ago, Moehring watched and wrote as landmarks were imploded and immediately replaced by moguls with even grander dreams. Then he helped the city – and the rest of the nation – make sense of the frenzied cycle of destruction and construction, putting the apparent chaos into historical context in his book, “Resort City in the Sunbelt: Las Vegas.”

Green said the book, originally published in 1989, was the first scholarly historical look at the city’s recent history, beginning in 1930.

“He did it at a time when Las Vegas really wasn’t taken seriously,” Green said. “He, more than anyone else, made this place a ground for a legitimate study. We know a lot more about our past and present because of him.”

Fry agreed. “There were other people who had clearly written about Las Vegas before, but not so much in a systematic, deeply researched and scholarly way,” he said.

And documenting the history of the resort city wasn’t an easy feat. Green mentioned that at the time when Moehring arrived in Las Vegas, the city was just beginning to eradicate the mob.

“Gene chose to study a city that was indeed very new, but also constantly changing,” Green said. “That makes demands on you for keeping up, and also juggling a lot of players and a lot of activity — he did that. It can be harder to teach and write about the recent past. I’ve written about Abe Lincoln — he won’t argue with me. You take a risk, because there are going to be different versions of the same event from people and sources among us. It’s a tough needle to thread.”

TEACHING: WHAT MATTERED MOST

Moehring updated and revised his history of Las Vegas, published three other books, numerous journal articles and chapters in books, all while taking on additional responsibilities at the university.

He served as chair of the history department twice, including during the period when the department added a doctorate program.

He sat on numerous committees, including the UNLV Senate, the Student Union Advisory Board and the UNLV 50th Anniversary Committee, to name just a few.

But his top priority has always been teaching.

He taught an “amazing range of classes quite successfully,” Fry said. The list included Nevada history, the history of science, the role of business in American history, the impact of technology on modern society, the urban West, U.S. domestic historiography and ethics and policy studies.

“He was always updating his lectures, making sure everything was current,” Green said. “When he knew his students needed night classes, and when very few of them were available, Gene was there. What ultimately mattered most to Gene — was the institution and his students.”

But you wouldn’t have heard about the long hours and dedication and growing acclaim from him, according to Fry and Green. They recall Moehring as very humble about his achievements and reticent to apply for teaching awards he would have easily won.

Moehring said teaching at UNLV was unlike what he would have experienced at the Ivy League schools of Harvard or Yale, in that he came across a wide array of students in his 40 years.

“You have the outright brilliant students, but then you have the good students, the satisfactory, and then the ones who are struggling,” he said. “So it really provides much more of a challenge.”

Moehring, however, seems content to leave the challenge, and responsibility of teaching a new generation to his colleagues. He plans to “get out of history altogether,” and volunteer his time with organizations such as Catholic Charities.

“Let the younger people do it,” Moehring said. “Michael Green is here — he can certainly pick up the slack.”

KEY TO THE FUTURE

In the classroom, Moehring emphasizes that history is about much more than remembering events of the past, telling students they’ll forget “this history stuff” two weeks after the final exam. But he says that understanding history will help them in many other areas, such as conducting research, thinking critically about issues and articulating ideas in writing.

He also taught his students that history is a tool for looking at current problems, like Las Vegas’ need to diversify its economic base.

“We’ve built about all the hotels we can build. We might build a few more, but that’s it. Tourism is about maxed out here. We’ll get to 50 million people (tourists), but that’s not a future. We have to diversify the economy in Nevada or we’re going to stagnate,” he said, mentioning data storage and solar energy as possible economic drivers in the future.

Moehring, and his contributions, will be long remembered, Green said.

“I cannot ever hope to repay what I owe him,” he said. “I don’t think Las Vegas can ever hope to repay what they owe him.”

Contact Natalie Bruzda at nbruzda@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3897. Follow @NatalieBruzda on Twitter.