UNLV ‘areas for expressive activity’ lead to a divided discourse

College campuses are supposed to be bastions of open expression. But during the recent presidential campaign rules to keep debate orderly at UNLV led to fractious discourse and left some students wondering where they could speak freely and safely.

Some observers pointed to UNLV’s rule limiting student activism to its designated “areas for expressive activity” — several spaces throughout the campus outlined in university policy — as infringing upon First Amendment rights.

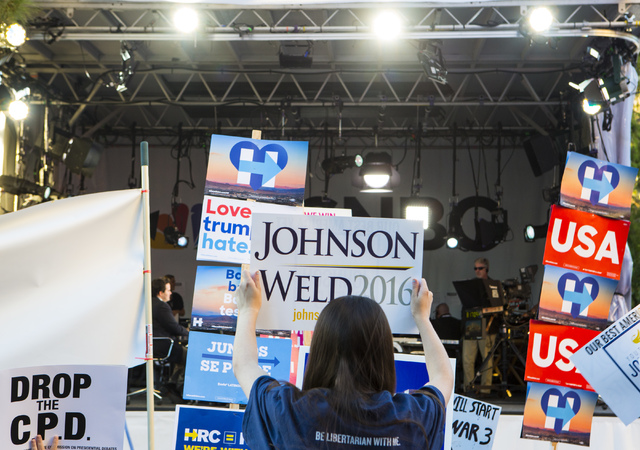

These areas, commonly referred to as free speech zones, also were designated as the only meeting place for politically affiliated groups leading to the Oct. 19 presidential debate between Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Hillary Clinton.

“The rules were a little bit difficult,” said Taylor Kruse, president of the UNLV Young Democrats. “It made meeting a lot harder, as well as recruitment.”

College Republicans adviser and political science professor David Fott said other college campuses have policies similar to UNLV’s to keep student political activities orderly.

“They are all poorly worded, in such a way to suggest that the First Amendment doesn’t apply on the entire campus,” he said.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education rates UNLV as a “yellow light” institution in its database of college speech policies. For an institution to receive the yellow light designation, a university’s policy has one of two problems, according to Joe Cohn, legislative and policy director for the foundation.

“It either infringes upon protected speech in a rarer context, or it is vague and gives the administration too much discretion, such that they might be able to wield it unconstitutionally, or use their authority and apply it in a way that does infringe upon protected speech,” Cohn said.

Gary Peck, a longtime civil rights and liberties advocate said UNLV has a checkered history with free speech and free expression, and suggested so-called expressive activity areas are unreasonable.

“The entire outdoor area of a university ought to be considered and treated as a free speech zone,” he said.

Cohn agreed with Peck’s assessment of UNLV’s history with this issue.

“I worked on combating these issues when I was a student at UNLV in the ’90s,” Cohn said. “And the issues predated my time when I was student.”

University administration, however, has adjusted its stance regarding its policy for expressive activity areas.

An updated policy defines “grounds open to the public” as the outdoor areas of the campus (lawns, patios, plazas) that are at least 20 feet from the entrances/exits of campus buildings and parking lots, and that do not restrict movement on campus walkways.

“We believe the updated policy more clearly articulates our commitment to assuring that all can exercise constitutionally protected rights of free expression, speech, assembly and worship on all university grounds open to the public generally,” said Tony Allen, a university spokesman.

AN EMERGING NORM

Despite the updated policy, students and other groups continue to utilize the various areas that have become familiar for political activity on campus.

Community leaders last month advertised a press conference to be held at one of the more frequently used zones, the walkway between the Lied Library and CBC buildings.

Those assembled there called for the university to take action against professor George Buch, who said in a Facebook conversation that he would alert Immigration and Customs Enforcement about students in his class who may have come into the country illegally.

“I find great irony in the fact that folks who were well-intentioned rushed to a free speech zone, which I consider an abomination to begin with, to call for the termination of Mr. Buch for exercising his free speech rights,” Peck said.

However, even with free-speech zones, some students feel politically muzzled.

UNLV political science major and aspiring law school student Jordan Escoto, who supports President-elect Donald Trump, said it can be difficult to voice his conservative views in class. He fears he’ll be branded a “racist” or “bigot.”

“I don’t speak up in class because there’s a hostility toward conservatives,” Escoto said. “I don’t like to cause problems in the classroom.”

Escoto created his own forum and group, the UNLV Campus Conservatives, about three months ago. He said the group was necessary because the College Republicans’ support for Trump seemed insufficient.

Fott added that students don’t need a campus to limit their views; they sometimes, as in Escoto’s case, do it themselves. Fott said he sees students choosing the “easy way of wanting to get along with others” by not being critical of opposite viewpoints.

“It’s one thing to not want to make a personal derogatory remark,” Fott said. “It’s another thing to not want to be critical of the idea — that someone else might not share the same view. That can hinder the student’s education.”

Peck also said muzzling people with differing viewpoints was dangerous.

“The way to fight most effectively is not to try to silence people with different points of view, but to engage them,” he said. “In no way should someone’s free speech rights be abridged because they disagree with me.”

FEAR OF CONFRONTATION

Nevertheless, such self-censorship happens.

Escoto said his group recently had a campus booth advertising pro-Donald Trump signs and banners. Although some approached the booth for information, others bypassed it, perhaps fearing conflict.

“They don’t want to have the confrontation,” Escoto said. “They just want to go to school and have their education.”

Jason Weinman, national director at Youth for Johnson-Weld, believes students are finding other ways to become involved in the issues they care about, beyond political discourse or politically affiliated groups on campus. Youth for Johnson-Weld was a major organizer for the Gary Johnson-Bill Weld presidential campaign.

“People don’t have terribly much faith in the system, or in the status quo,” he said. “The enthusiasm we saw on college campuses for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012 — I don’t think that converted over to the current election. I think there’s been a little bit of a shift with regard to faith in the system, and not giving the government so much control in our lives.”

Despite what he sees as a shift, he believes current students are just as concerned about issues as in previous years.

“They’re not apathetic or uninterested,” he said. “I just think they haven’t found the best way to contribute and to build a more prosperous society, and solve social issues. I don’t think they’re convinced that electoral politics is the pathway.”

Contact Natalie Bruzda at nbruzda@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3897. Follow @NatalieBruzda on Twitter.