UNLV clinic’s closure leaves patients scrambling for options

Five weeks ago, UNLV suspended a maternal-HIV program without warning the medical personnel who run the program, or their patients.

While 62 patients — women, pregnant women, infants and children — have seen their medical care left in the lurch for more than a month, Shawn Gerstenberger, the dean of UNLV’s School of Community Health Sciences, said his first priority was to see that the most needy of patients, or those who had appointments scheduled, were hooked up with providers.

But it took until this week for UNLV to begin placing patients into the care of UMC’s Wellness Center, a clinic dedicated to caring for HIV/AIDs patients, most of whom are adults.

Meanwhile, questions have been raised about how the closure was handled.

“No one had told us,” said Simona Johnson, whose 4-year-old adopted daughter, is HIV positive. “I didn’t know myself until I went down there to make an appointment. How come no one had called? How come no one had sent out a letter in regard to this? Where are we supposed to go? Who’s supposed to take patients like this?”

Abrupt closure

The program, created in 2005, is the only comprehensive maternal-child HIV program in Southern Nevada that has worked to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission.

UNLV professor Dr. Echezona Ezeanolue, who created the program, in 2012 brought on Dina Patel, a pediatric nurse practitioner, when he secured a federal grant to pay for the program.

“I left everything I knew behind because I believed in what he was doing here,” Patel said. “He was making a difference.”

When Patel and Ezeanolue were told on Sept. 15 that the program was being suspended that day, it was presented as a paperwork technicality.

They were told they needed a memorandum of understanding in place to see patients in a UNLV School of Medicine pediatric clinic, which was recently transferred from the University of Nevada, Reno.

“We thought it was going to be an easy-to-do thing, that that’s all that needed to be taken care of,” Ezeanolue said. “We have not been told of any other issues.”

UNLV President Len Jessup, who learned about the issue this week and alerted the state Board of Regents on Wednesday, said there have been irregularities with the way the grant is being administered.

“Things … look unusual to us, so we’re looking into it,” he said, adding that he learned about the issues with the program only a few days ago.

Gerstenberger, also acting dean of UNLV’s medical school, would not comment on the irregularities, but said he initiated an administrative audit of the program on Tuesday, more than a month after the program was suspended. He said it took that long because he was reviewing the program.

“I asked some questions, and didn’t get sufficient answers,” Gerstenberger said. “I thought it was in the best interest of the patients to move to the administrative audit.”

UNLV’s office of research integrity will investigate Gerstenberger’s concerns, and should provide a report in about 60 days.

One of the issues appears to be the MOU. When asked whether one had previously been in place, Gersternberger said “there was, and there wasn’t,” adding that it would be inappropriate for him to share more on the topic.

“There’s multiple issues with the MOU,” Gerstenberger said. “I can’t get into any detail on that. It’s a requirement that we have to have that in place to operate the clinic.”

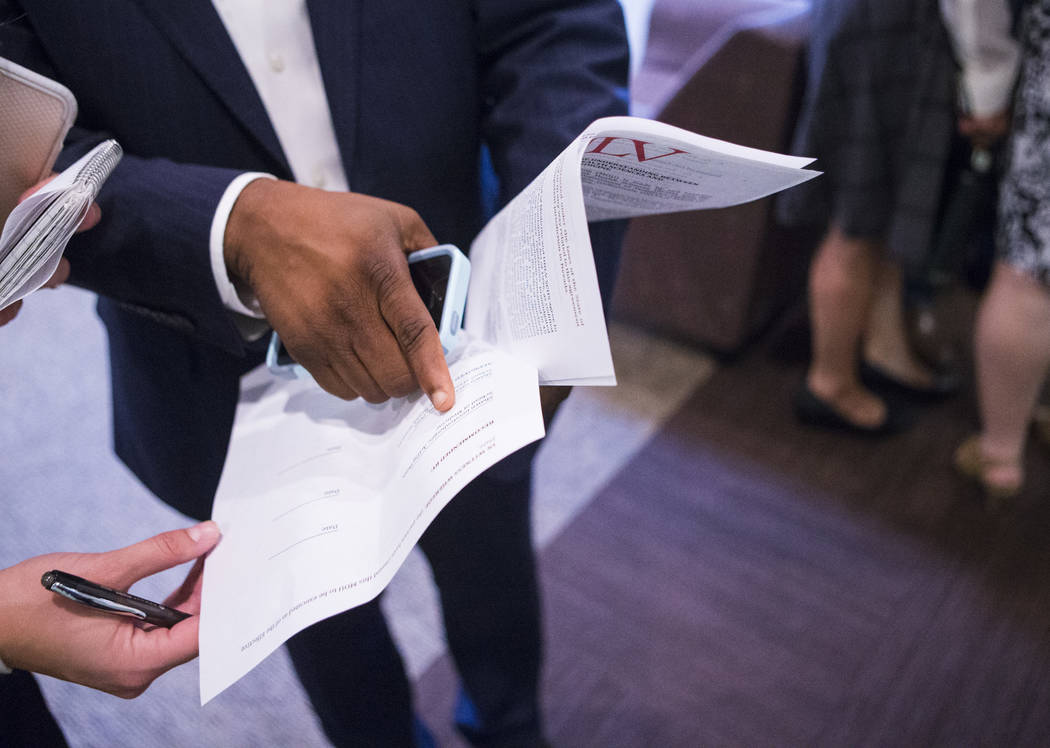

About three weeks after the program was suspended, Patel and Ezeanolue said they agreed to the terms of an MOU that was emailed to them, but haven’t heard anything since.

“We went from that to nothing. We heard that our patients are being transferred and we need to give up all of our patients and their contact information.”

Unofficially, Ezeanolue has also heard that he’s under investigation by the federal government.

“If you’re under investigation, why don’t you wait until the investigation is done before you close the clinic?” Ezeanolue said, adding that the program’s license remains active and its malpractice insurance is still covered by the Nevada System of Higher Education.

Money from the federal grant — about $195,000 a year — are also waiting to be spent. Patel said she and Ezeanolue were notified on Aug. 1 that they would receive the money, which pays for salaries, for another three years.

“I don’t know why they’ve been treating us so unfairly and not giving us our program back,” Patel said. “I know for a fact that no one else is going to take care of this program like we have. I still have my medical license, I’m still getting paid, so why can’t I see my patients?”

A stigma

Elena Ledoux, a longtime family friend of a mother whose daughter is HIV positive, has spearheaded an effort to get answers from the university.

“First I went to the dean,” said Ledoux, who has acted as spokeswoman for the family to protect the daughter’s identity. “I sent an email to him. I called every single member of his cabinet. I said, ‘if you drop the ball, kids are going to die.’ … We can’t afford for them to mess this up, which is what they are doing.”

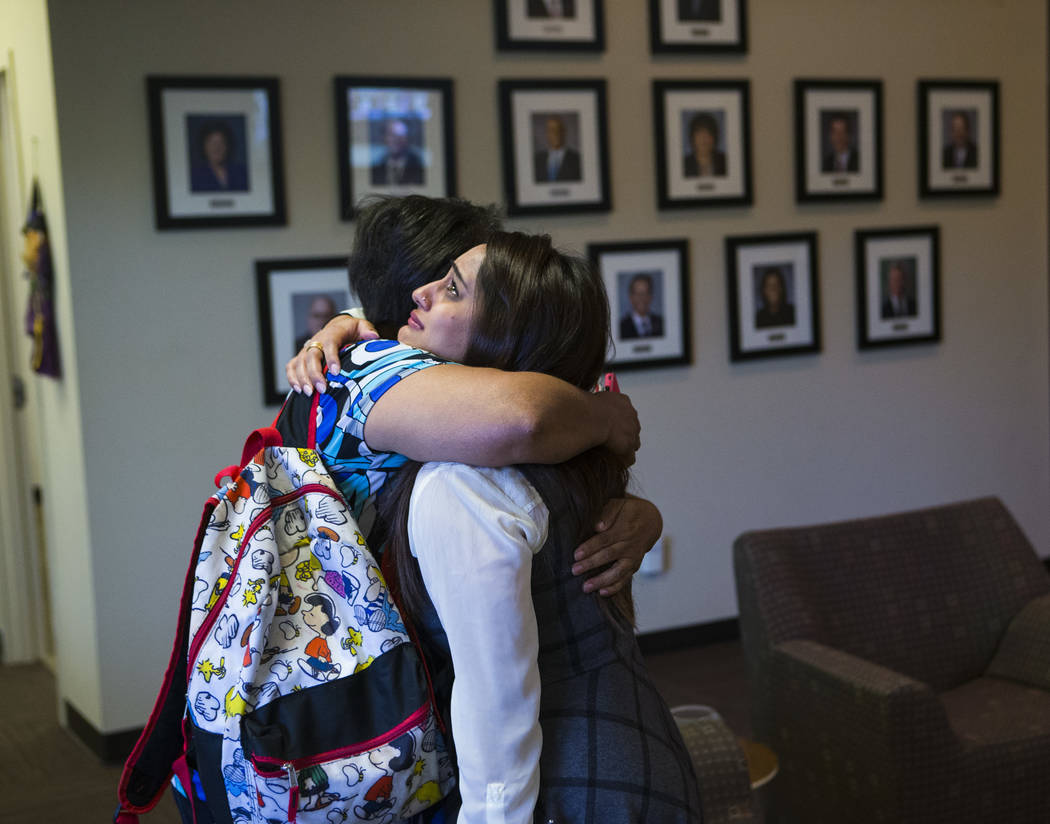

Ledoux has witnessed the rapport her friend’s daughter has built with Patel and Ezeanolue, who have treated the girl for two and a half years, she said.

“She’s developed a very strong bond with her providers,” she said. “To take that away from her, without warning, that’s devastating.”

Ledoux is worried that the experience of going to a mostly adult clinic versus a pediatric office will have negative effects on her friend’s daughter and other HIV-positive children. Ledoux said introducing the realities of HIV as a disease to the children who have it is a very gradual and emotional process.

“There’s a stigma associated with it,” she said.

UMC began scheduling patients this week — five weeks after the program was suspended — with the first appointments expected as early as Friday, according to Danita Cohen, spokeswoman for UMC.

Gerstenberger said UNLV also hired a case manager to help the patients on Tuesday.

But some patients have been left waiting for crucial care.

Johnson, who still didn’t have an appointment for her daughter as of Thursday night, said the presence of HIV was dormant in her daughter’s blood, but now, it’s back.

“I’m still giving her the same dose of her medication, but is that dose correct? Maybe that dose needs to be changed,” Johnson said. “Her pediatrician filled it for one month, but after her month is up, who’s supposed to fill it? This isn’t cough medicine.”

Johnson and Ledoux brought their concerns to the state Board of Regents meeting on Thursday, much to the surprise of the board. Regent Rick Trachok said he was first notified there was a problem with the program after receiving a call from a patient on Wednesday.

A couple hours after public comment a sense of tension filled the room.

“I was surprised at the beginning of the meeting tonight,” said Kevin Page, chairman of the Board of Regents. “Why is it hard to communicate some of this stuff?”

Page said he asked for UNLV to come back to the board with a timeline on what’s happened, along with data and more information.

“Depending on what comes back, we could have a meeting about it,” he said. “No. 1 is that we want to make sure the kids are being served, that they’re getting their needs met.”

Contact Natalie Bruzda at nbruzda@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3897. Follow @NatalieBruzda on Twitter.