UNLV professor finds new voice in Great Courses

College professors receive feedback about their classroom performance from all sorts of sources, ranging from student evaluations to online professor-rating sites.

But John Bowers, an English professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, also receives feedback in a form other professors would envy: fan mail, almost all of it from students he’s never even met.

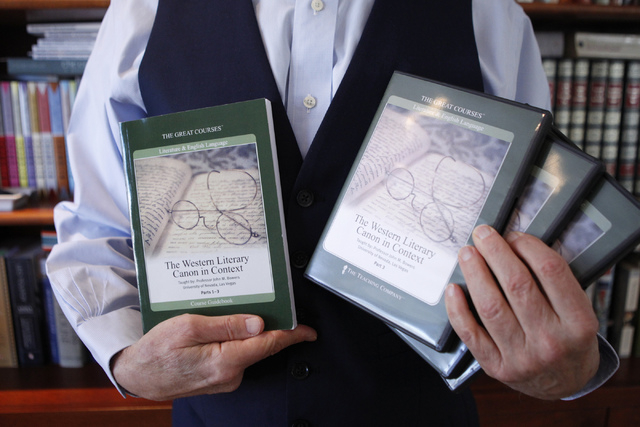

Bowers created a course called “The Western Literary Canon in Context” for The Great Courses, a catalog of college-level classes in just about everything from history to science to cooking.

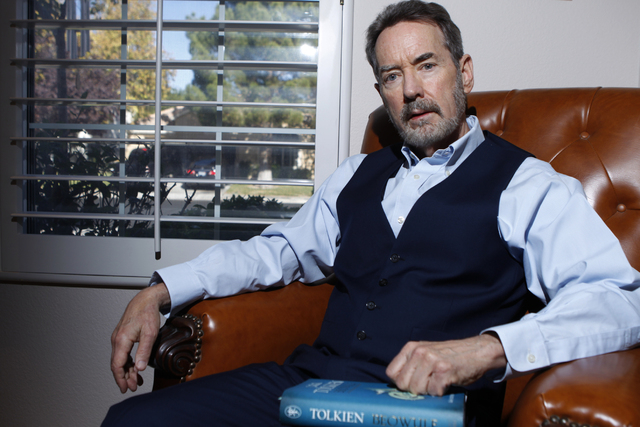

His career made him an attractive candidate for the education company. Bowers’ teaching honors include UNLV’s Barrick Distinguished Scholar Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship and he has written scholarly works about literary classics and canonical authors. Most recently, Bowers tracked down a previously undiscovered book by J.R.R. Tolkien that the “Lord of the Rings” author began during the 1920s but didn’t complete. Bowers is writing a book about that lost work and the ways that project influenced Tolkien’s later career, including his fantasy fiction.

Bowers joined UNLV’s faculty in 1987, and says The Great Courses gig arrived in 2005 as “very much a fluke, out of the blue.”

“One of the recruiters for The Great Courses just happened to come to Las Vegas with his wife, who was here on business,” he says. “He decided that since he was here, he’d investigate the UNLV faculty. He did an online search to see who won teaching awards, then he contacted us and asked if he could come to our classes and record a lecture.”

William Schmidt, director of academic recruiting for The Teaching Co., which produces The Great Courses offerings, says the company always is looking for prospective teachers of new courses. The company employs criteria that include teaching awards, student evaluations and a candidate’s published work and academic achievements.

Schmidt says Bowers “has won numerous teaching awards, students rave about him, and he teaches a number of adults, which is unusual in a college-level class.

“He’s got a lot of experience. He stood out.”

The initial pool of professors for a single course of The Great Courses can number in the hundreds and even the thousands, Schmidt says, and the ideal professor will be both an expert in his or her field and have a passion for the subject. The candidate also must have both the ability to convey information to a general audience in an understandable, interesting way and the ability to “establish rapport with a general audience.”

After several rounds of cuts, finalists — typically no more than two or three, Schmidt says — are invited to The Teaching Co.’s studios in Virginia to film a single 30-minute audition lecture.

Schmidt says the biggest challenge company talent scouts have is finding professors “who can translate wonderful teaching from a classroom into a studio environment.”

The company provides a staff consisting of producers, editors, writers, graphics people and others who can help professors translate material to a video audience.

For his audition, Bowers prepared a lecture about “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” a mid- to late-15th century poem.

But it turned out that Bowers was more acquainted with the rhythms of show biz than he thought.

“They said I’d probably have to do it in two or three (takes), and I nailed the first one. It came in at exactly 30 minutes,” Bowers recalls with a laugh. “And everybody in the room looked at each other and said, ‘This is it.’ ”

Bowers teaches courses at UNLV about that body of literature known as the “Great Books” — among his teaching interests are late Medieval English literature, Chaucer, world literature, Shakespeare and Tolkien — but the course he recorded for The Great Courses represents a different take on a common theme.

There are “a lot of Great Books courses,” he explains, but his idea was, “how about if we talked about how a book gets to be considered a ‘Great Book’? That was a topic that interested me, the building of the literary canon, how books get in and stay in.”

So, in what he calls “the hardest and most stressful thing I ever did,” Bowers crafted 36 half-hour lectures, all pretty much from the ground up.

Because the course was a new one, “I really couldn’t recycle my UNLV lectures,” he says. Then, in addition to writing the lectures and gathering supplemental material that would be incorporated into the video presentation, he wrote a printed manual that accompanies the course.

Bowers spent his 2007 summer break researching and beginning to write lectures. The following summer, he returned to the company’s Virginia studios for recording and found it more challenging than his initial audition.

“It lacks the immediate human feedback,” he says. “When you’re in front of a live audience, you can see the lights go on in the students’ eyes. You can get them to laugh, and you can get responses. In the studio, none of that happens.”

He laughs. “I guess if I had better sense, I would have been more scared.”

But Bowers also found that performing for a camera and teaching in a classroom share a similar dynamic. In both cases, the teacher attempts to convey ideas while striving, also, to hold his or her audience’s attention. In some ways, he says, “a lecturer is a performer.”

During filming, Bowers became aware of a mannerism or two that didn’t translate well to video. For instance, he saw that he tended to lean on the lectern on the fairly simple set and sway back and forth.

“They speeded up the film to show me, and I looked like a metronome going back and forth,” Bowers says with a laugh. “So I had to make a point of putting my hands on the lectern, just to still myself so I wouldn’t sway back and forth.”

Except for the setting, the lectures could have been given in one of Bowers’ classes at UNLV.

“They recruit university professors, so we’re teaching very much at the university level,” Bowers says, noting that he didn’t dilute or dumb down the material for his video audience. Instead, he imagined his unknown video student to be “a bright learner who was anxious to learn,” and Schmidt says that’s not far off.

Market research drives much of the development of new courses, Schmidt says, and “I think the bulk of our customer base — the ones who really drove development of the course — are highly educated, creative lifelong learners, people like doctors, lawyers, teachers and business professionals who had a good time (academically) in college … and who went and got a graduate degree.

“Then, once they entered the professional world, they missed that sort of liberal arts experience and wanted to continue learning. They’re really the core of our customer base. But we also have a lot of people who are just curious about something — for example, an applied field like photography, which has become one of our best-sellers recently.”

The Great Courses program has a diverse customer base, Schmidt says, and Bowers suspects his experience in teaching UNLV’s diverse student body may have helped to prepare him for the video gig.

At UNLV, “we have students right out of high school, we have mature students, we have grandmothers, we have men and women who have just come out of the military,” Bowers says. “We have a very diverse classroom population, and we learn how to hit the target for that kind of wide range of students and age groups.”

Bowers’ offering for The Great Courses was released in 2008 and is available in CD, DVD and audio download in The Great Courses catalog (www.thegreatcourses.com) as an “evergreen title.” That, Bowers jokes, means that, because of its timeless topic, “it will outlast you and me.”

And now that his advance has been repaid, Bowers says he even receives “a royalty check a couple times a year.”

He laughs. “Of course, I could still make more money teaching summer school.”

But Bowers says he didn’t do it for the money. Rather, the video offering is a means of reaching potential learners who might otherwise not get to take such a course and, he says, a way to put into a more permanent, more tangible form the otherwise ephemeral art of the classroom lecture.

Besides, remuneration comes in all sorts of forms. There are, for instance, that fan mail Bowers still receives, which, he says, “makes me realize what a diverse audience there is out there.”

“I got an email fan letter from a 17-year-old in London who told me he was going to university to major in history and, after listening to the lectures he decided to switch to English literature,” Bowers says.

“I also had a handwritten fan letter from an 80-year-old retired teacher in Alaska. She said her eyesight was so poor she couldn’t read anymore, so she listened to lectures like this to remind her of how much she loved literature.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.