Unvaccinated students pose risk to others

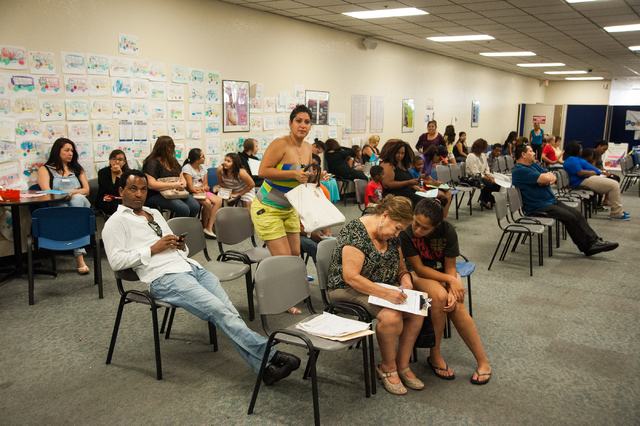

A tide of 400 children arrived at the Southern Nevada Health District’s main clinic each day last week.

Another 400 came daily to the east Las Vegas clinic, a surge matched at the health district’s North Las Vegas and Henderson clinics. The numbers were driven by procrastinating parents scrambling to get their children vaccinated before classes begin Monday in the Clark County School District.

The highest number of children, however, will be seeking shots on Monday if history holds true.

“Parents don’t like that call on the first day of school telling them to come pick up their child and get them vaccinated, or the student can’t come back,” said Bonnie Sorenson, the health district’s director of nursing and clinical services, whose staff members sometimes hear an earful from angry parents.

But state law requires students to be vaccinated against a slew of diseases, some of which have seen a recent resurgence. Numerous studies document the rise of polio and pertussis associated with unvaccinated children in other states and the steep cost of containing an outbreak.

A parent’s refusal to remove their unvaccinated child from school could end in a misdemeanor charge, according to Nevada law.

But thousands of Nevadan families resist vaccinating their children for anything — not diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), tetanus, polio, hepatitis A and B, varicella, measles, mumps or rubella, grasping at the exemption in state law for those claiming vaccinations violate their religious beliefs.

And their children are allowed to remain in school.

“It really does put those kids at risk,” said Lynn Row, the Clark County School District’s director of nursing. The district of 315,000 students enrolled 6,135 unvaccinated students in 2013-14. That’s about 2 percent.

About 70 percent of these children fell under the religious-belief exemption. The remaining 1,806 unvaccinated children claimed a medical exemption, which requires a doctor’s note.

Every state requires that public school students be vaccinated, and every state also allows medical exemptions, which usually apply to children who are allergic to vaccine ingredients or who have weak immune systems due to chemotherapy or other conditions.

While Row supports the medical exemptions, she said all other exemptions create a danger. Not only are unvaccinated students at increased risk for contracting illnesses, they’re also exposing those too medically fragile to be vaccinated to risk and relying on the “herd immunity” of vaccinated students to shield them from diseases, Row said. She’s particularly concerned because pertussis is on the rise in the West.

California recently announced more than 4,500 reported cases of pertussis since the beginning of the year, far surpassing the 2,532 cases in 2013. The number of reported cases nationwide increased by 25 percent for the first half of 2014 compared to the same time period of 2013, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nevada hasn’t seen such an increase yet. It reports 31 pertussis cases so far this year, and had 121 cases in 2013. That may have to do with a difference in the states’ vaccination laws.

California is one of 19 states that permit parents not to vaccinate their children solely because of philosophical or personal beliefs.

“You can just say. ‘I don’t believe in it,’ ” Sorenson said.

States with such “easily obtained exemptions” can have two-and-a-half times as many unvaccinated children as other states and usually report higher rates of pertussis, according to the federally funded National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Sorenson said it’s a good thing Nevada doesn’t allow personal-belief exemptions.

“We’ve been told that’s the reason why our vaccination rate is so high, she said.

The school district’s reported 98 percent vaccination rate of last year outshines the national average, which varies by vaccine, but usually stands at about 95 percent, according to the CDC.

“We’ve knocked the noncompliance rate way down,” said Row, recalling that just a few years ago 9 percent of Clark County students didn’t have their vaccinations.

Attempts to reach Vaccination Liberation, a national grass-roots network dedicated to preserving parents’ rights to abstain from having their children vaccinated, were unsuccessful. The group has a Nevada chapter, which also could not be reached for comment.

Colorado reports the worst vaccination rate among youth — 80 percent to 90 percent, depending on the vaccine. It’s one of the states that allows personal-belief exemptions. A study of all pertussis cases for Colorado youth over more than a decade found children exempted from vaccinations were 6 times more likely to get the disease and 22 times more likely to acquire measles, according to the center.

In the nation’s largest measles outbreak since 1996, an unvaccinated Indiana student returned from Romania in 2005 and introduced measles into a group of children at a church gathering. Health officials confirmed 34 cases of the measles, 32 of which involved unvaccinated youth, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

The estimated cost of containing one measles case is $142,452, meaning the Indiana outbreak cost about $4.8 million.

The cost of one measles vaccine, which is called MMR and also includes the mumps and rubella vaccines, averages $20, according to the CDC.

Like Nevada, Indiana allows a religious exemption. Row fears the religious exemption will be taken advantage of by parents because the state doesn’t allow a personal-belief exemption.

“Now, vaccinations are against their religious beliefs,” she said.

Contact Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279. Find him on Twitter: @TrevonMilliard.