Workers: Morale of Clark County schools’ support staff ‘tanked’

Some days Chip Lydick goes straight to his school bus to avoid the negative atmosphere in the offices at his Clark County School District bus yard.

“Sometimes going into the squad room or into the office itself, it’s just there’s such a heavy cloud of anxiety or anger,” the bus driver said. “It’s hard to deal with that sometimes.”

Lydick senses the toxic environment that’s sweeping throughout the rest of the district’s support staffers, who feel underappreciated, underpaid and overlooked.

Discouragement in the ranks of the district’s roughly 12,000 support employees — essentially all the nonteaching, police or administrative positions — is rampant, interviews with more than half a dozen support workers indicate.

Morale for the district’s custodians, clerical personnel, bus drivers and other support workers has only gotten worse in the face of stagnant salaries, rising health insurance costs and two years of budget deficits that have weighed heavily on support staff.

“We all feel underappreciated,” said Serena Koerner, a registrar at West Career and Technical Academy. “We all feel like we’re the first to go and the last to be made whole, that our concerns aren’t considered.”

That leaves new Superintendent Jesus Jara and other district officials with a difficult challenge: trying to convey their appreciation for employees who feel that they’re regularly being given the short end of the stick — and often are.

Feeling cheated

Last month, an arbitrator ruled that the district did not have enough money to provide support staffers a 2 percent salary bump for the 2017-18 school year.

Teachers and administrators were awarded raises through arbitration, although teachers have not yet received that raise because the district has fought it in court.

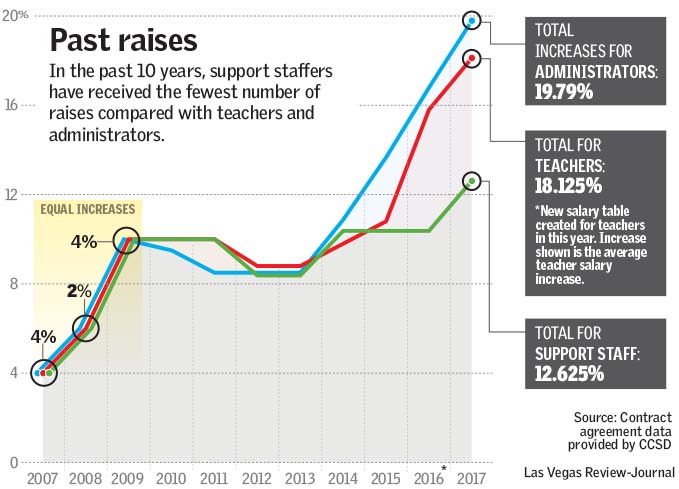

Historically, support staffers have received fewer raises in the past 10 years compared with those two groups, according to district data. They’ve received five wage increases from fiscal years 2007 to 2017 for a total of 12.6 percent in raises, according to district data.

Teachers, meanwhile, have received seven raises for a total of roughly 18 percent, and administrators received seven for a total of nearly 20 percent.

The district said Friday that the School Board had authorized the superintendent to offer a one-time payment to all employee groups in an effort to boost morale.

But that may not be enough to erase the damage.

Support staffers also apparently bore the brunt of recent budget cuts — at least from the 2017 deficit.

Following that shortfall, 240 support employees were reassigned to a different job, compared with 16 school-based administrators. Six support staffers were ultimately the only ones left without a job after the reassignment process, according to district data.

The district could not provide such data for the most recent $68 million deficit as of Friday.

Some of those reassignments or cuts could be attributable to regular staffing changes and not the deficit, the district notes.

Regardless, the deficits still left an indelible mark on morale.

“In the last few years, it’s really tanked,” said Kathleen Saludares, an office specialist in energy management. “We had people retiring that had no intentions of retiring. They just said, ‘Enough. I just can’t take this anymore.’”

Overworked, promotion prospects dim

On top of stagnant pay and higher health care costs, some employees say they’re expected to do more on the job.

Bus drivers in particular say the district’s constant driver shortage forces them to pick up additional routes that aren’t filled, often putting them behind their schedules.

“It’s very frustrating because I get to a stop to pick up these kids, these kids are now complaining to me, ‘Why are you late, why are you late?’” Lydick said. “I get to the school, the school’s complaining, ‘Why are you late?’ We get parents calling in, ‘Why were they late?’ It’s a snowball effect.”

As of July 31, the district was expecting 71 vacancies out of a workforce of 1,659 drivers when school begins Aug. 13.

Promotion is one way of getting a salary boost, but some employees say that those who are hiring in the district often have their minds made up about who they’ll choose for a job before they post it.

“You just, you can’t get anywhere,” said Sharon Cooper, a construction documents clerk. “There’s so much favoritism that goes on it’s just ridiculous.”

Like others, Cooper said she is looking for jobs outside the district, even though that may mean taking a cut in pay.

Turnover rate among support staffers and school police has slightly increased over the past six years. In the 2012-13 school year, roughly 5.7 percent of those employees left the district, according to district data. In the 2017-18 year, that number was 6.9 percent.

Meanwhile, many support staffers have grown disillusioned with their union, the Education Support Employees Association. The group is locked in a battle with the local Teamsters union in a fight to represent support staffers, a fight that’s awaiting resolution by the state Supreme Court.

“We hate them; we don’t want them,” Saludares said of the ESEA. “They need to go bye-bye. They do nothing for us, nothing.”

ESEA leaders did not respond to requests for comment.

New leader, new hope

Despite the slings and arrows, not all support workers are miserable.

Andrea Gorman understands why her colleagues are feeling down but said she tries to keep a positive attitude.

“It just makes me really happy to see the same kids every year,” said Gorman, a special needs bus driver who’s hoping to go back to school one day. “I’m very excited to see the kids again.”

Jara has acknowledged that the district’s precarious financial state presents an obvious challenge to efforts to boost morale, but he vowed to communicate to support staffers how much the district appreciates their work.

But to Koerner, the registrar, statements of appreciation mean nothing.

“No more lip service,” she said. “Validate us. Don’t tell me how much you appreciate me. Show me how much you appreciate me.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.