Esmeralda County has few people, fewer jobs, but don’t talk about consolidation

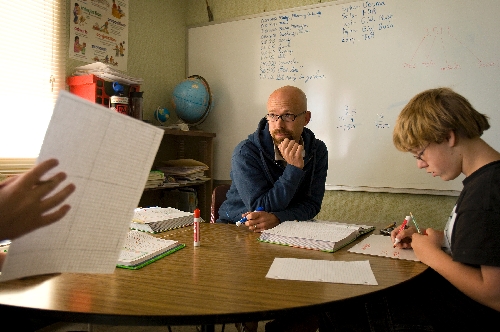

SILVER PEAK -- When the clock hits 8:15, John Scates rings the morning bell and steps outside to watch his students raise the flag and recite the pledge.

Silver Peak Elementary is the only school in the smallest town in Nevada's loneliest county, so taking attendance is a breeze. Scates can see the problem with a single glance. Eight faces where there should be 10.

"Where is everybody?" he asks.

It's a good question, and Scates is not the only one asking it.

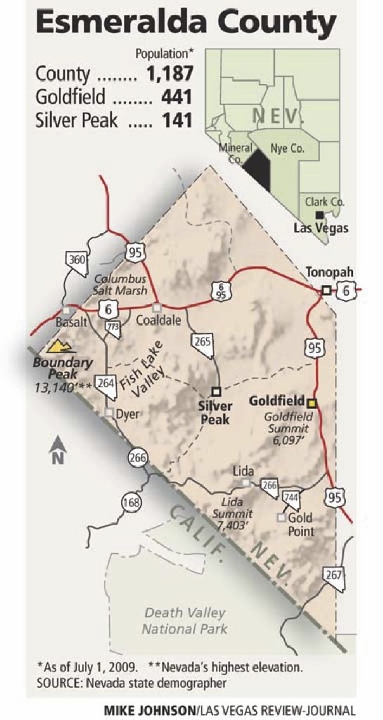

According to the latest state estimates, the population of Esmeralda County slipped below 1,200 last year for the first time since 2004.

Leading the slide was tiny Silver Peak, which lost 41 residents to a mine layoff in 2009. That amounts to almost a quarter of the community's total population, easily the largest decline by percentage of any city or town in the state.

County residents downplay the decrease. The population has bounced along at about 1,000 for decades now, they say, but it has never dipped much below that.

Those just passing through on U.S. Highway 95 are left with a different impression.

The main route from Las Vegas to Reno crosses 110 miles of Esmeralda, but the only town it touches is Goldfield, a county seat that resembles an outdoor museum exhibit on the early 20th century.

Viewed through a windshield at 65 mph, the rest of the landscape looks untouched or abandoned. Deserted. A ghost county.

Where is everybody?

The fall

"The first time I drove through here 40 some years ago, there was a house for sale, and I thought, 'Who would ever want to live in a place like this?'" laughs Juanita Colvin, a proud resident of Goldfield since 1976. "You just never, never know."

Colvin has served as the county's only justice of the peace for almost 20 years, a job she describes as mostly clerical.

She has no staff, but she still finds time to lead tours of Goldfield's historic courthouse.

The two-story stone fortress has been in continuous use since it opened in 1908, and county business is still conducted there using some of the original furniture.

Esmeralda was a very different place a century ago, when the central Nevada gold rush was in full swing.

Back then, Colvin says, the county was home to 28 different townships, none larger or more elaborate than Goldfield. With a population of about 20,000 people, it was Nevada's largest community from 1903 to 1910, and the railroad kept its shop windows stocked with fresh flowers, fashionable clothes and other big-city niceties.

Eventually, though, the mines played out and the jobs dried up. By the end of World War II, Goldfield was all but gone.

These days, Esmeralda County's ups and downs play out on a much smaller scale, hinting at a sort of equilibrium.

"I don't think it's ever going to dwindle down to nothing," Colvin says.

HIGH AND LONESOME

Esmeralda County is a diamond-shaped expanse of dry mountains and high desert wedged between Nye County and the California border.

Its 3,589 square miles includes the highest point in Nevada, 13,140-foot Boundary Peak, and fewer people than you will find at a typical Las Vegas middle school.

With one person for every 3 square miles of territory, Esmeralda ranks as one of the most sparsely populated counties outside of Alaska. In places, though, the county seems far emptier than that. But for a few true frontier-dwellers, nearly everyone lives in one of three spots: the mining outpost of Silver Peak, the sprawling farm community of Fish Lake Valley and the long-faded county seat of Goldfield.

"All three communities are very different," says Robert Aumaugher, superintendent for the Esmeralda County School District. "It's kind of like being in three different states."

All but 1 percent of the county's land is under federal control, but the influence of government at the local level is limited at best.

R.J. Gillum has represented Goldfield on the Esmeralda County Commission since 2002, when he won his seat in a game of high card that broke a 107-107 Election Day tie. He is proud to say the county has no building codes and few other regulations. Of course, it also doesn't have a hospital, a high school, a supermarket or a single chain restaurant.

"You come here to die or you come here to live," he says. "I don't know if it's the pioneer spirit, but you can't pry me out of here."

As locals like Gillum will candidly tell you, the state's official population estimate of 1,187 is probably high. The real number, they say, is closer to 1,000 or less.

And that population is graying, as retirees come in search of cheap land and solitude and the county's young people leave to find work and excitement.

According to county estimates, the median age in Esmeralda is 44. Statewide it's 33.

SOMETHING IN THE WATER

The hillside playground at Silver Peak Elementary offers a panoramic view of the town's reason for existence: the vast Clayton Valley dry lake bed, better known as "the playa."

Beneath this bleached expanse of dust and clay lies a deposit of lithium suspended in briny groundwater.

Mining began in the mid-1960s. Today the playa is dotted with pumps and power lines and man-made ponds.

It is the only lithium mine in the nation.

The brackish water is pumped from the ground and moved through a series of evaporation ponds to refine the mixture, a process that takes about two years.

Once it reaches the proper concentration, the brine is piped three miles to the mill in Silver Peak, where it gets turned into the base chemical lithium carbonate and several other compounds.

The material has a wide variety of applications, from scrubbers that keep deadly gas from building up in space capsules to eyeglasses that tint when exposed to the sun. It is also used in lubricants, pharmaceuticals, countertops and lithium batteries.

With "the battery industry coming on strong," mine officials hope to see a surge in demand for their product, says General Manager Joe Dunn.

The mill still operates 24 hours a day, but orders have dropped significantly as a result of the worldwide economic downturn. That's what triggered last year's layoffs.

North Carolina-based Chemetall Foote Corp. now employs about 30 people at its Silver Peak plant, with plans to add eight more workers later this year.

Dunn says the mine has plenty of life left in it. Current projections call for operations to continue there through 2020.

CONSOLIDATION

Talk of Esmeralda's population inevitably turns to questions about its viability.

Few officials have publicly suggested doing away with the county, but the idea has come up from time to time.

The word often used is "consolidation," but to the locals it sounds more like "assimilation." Or maybe "death."

"I have seriously looked at consolidation. Every time it's been, 'You'd better not or we'll shoot you,'" Gillum says. "We'll lose our identity if we do that, you see."

One advocate of redrawing the county lines is longtime Nevada jurist John Davis, whose Fifth Judicial District includes Esmeralda, Nye and Mineral counties.

Davis has long favored combining Esmeralda County with the northern part of Nye County, and making the southern portion of Nye into its own county with Pahrump as its seat.

"We're just so different," Davis says of central Nevada and the south. "It's rather an incompatible marriage."

As for Esmeralda County, the judge says it no longer makes sense to govern such a small population as a separate entity.

The county sees so few cases that Davis holds court in Goldfield about once a month.

"I haven't done a trial there in at least five years," he says. "It's just inefficiency."

But County Commissioner Bill Kirby doesn't buy it. If Esmeralda is so inefficient, he says, why is it one of the only Nevada counties in the black right now?

"We've heard that noise before," Kirby says. "But we're holding our own, and we like our autonomy."

Gillum says the county has so much money in reserve that it could cover its comparatively modest $4.5 million budget for more than a year with no outside revenue whatsoever.

Of course, much of that black ink is imported. The county's single largest source of revenue is the consolidated tax money it gets from the state.

Last year, Esmeralda received $1.4 million in so-called C-tax money, roughly $1,160 for each of its 1,187 residents. Clark County got $795.6 million, or $408 per resident.

As Gillum puts it, "We're the smallest county in the state, as you know, but we're not the poorest."

There is also history to consider.

"Eliminating Esmeralda County is about more than losing county offices and jobs, or even a county seat of government. It's about losing a political identity that goes back to the founding of Nevada Territory in 1861," says former State Archivist Guy Rocha. "Esmeralda is one of Nevada's original nine counties. In fact, the bill creating the territorial counties ... listed Esmeralda first."

Then there is this: If the county were to be dissolved, it could deal a death blow to an already shaky labor market, particularly in Goldfield.

With about 90 jobs, roughly half of them full-time, county government is Esmeralda's single largest employer.

THE ALTERNATIVE

For an up-to-the-minute population estimate for Silver Peak, the town's only bar is a good place to start.

Owner Kenny Polman and his volunteer bartender, Donald Moore, can come up with a total in a matter of minutes by doing a quick, house-to-house count in their heads. Tonight the number is 83, including them and their customers.

It's a Wednesday, and a half dozen people are lined up along the L-shaped bar, which Polman decorated himself with a mosaic of old tiles. A few dusty pellet rifles rest on the bar where someone was taking them apart and working on them.

Two dogs doze on the floor.

A young family -- husband, wife, three kids and a puppy -- shoot pool in the corner with Moore's wife.

The bar is called Alternative, as in "an alternative to a real job," but it hasn't quite worked out that way for Polman.

"It was a wild ride for the first five years, but I don't think it's made any money since I bought it," he says. "It's not a fun hobby, so I don't know what I'd call it."

The town used to have two 24-hour watering holes. Now it can't even support one. Alternative is only open part of the time, which basically means whenever Moore is there to unlock the door.

He tries to open the bar for at least a few hours most evenings, after he gets off work at the lithium mine and rides his ATV home to eat dinner.

Moore brings his own drinks and works in the bar for free, he says, because it gives him and his neighbors something to do besides sitting home in front of the television.

He and Polman acknowledge that Silver Peak has fallen on hard times lately, but neither of them seems too worried about it.

"We've both got property here, and I'm not interested in leaving," Moore says.

Asked what might improve things in the town he has called home since he was 9, Polman has to think for a minute. Then he gives his answer like a true bar owner: "Drunks."

THE LAW

Folks in Silver Peak are mostly left to police themselves these days. The Esmeralda County Sheriff's Office doesn't keep a resident deputy there anymore.

The department is stretched pretty thin as it is, with just five patrol officers to cover an area larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

Most of the action comes along U.S. 95, where Sheriff Ken Elgan and company race to accidents and chase down speeders. The department writes roughly $500,000 worth of traffic citations each year, an important source of revenue but not enough to sustain the department.

At the western edge of the county, where Fish Lake Valley meets the steep wall of the White Mountains, the trouble lately is drug traffickers from out of state.

In recent years, several large marijuana growing operations, complete with elaborate irrigation systems, have been spotted and destroyed by authorities in the Boundary Peak Wilderness, miles from any house or paved road.

"It's the perfect place," Elgan says. "You've got a whole lot of canyons with water coming out of them and remote access."

Elgan just won his fourth term as sheriff when no one filed to run against him. His wife, LaCinda, won her second term as the county's clerk and treasurer the same way.

They live in Fish Lake Valley, a 150-mile daily commute from the courthouse in Goldfield.

Elgan has been known to save his neighbors the "trip into town" by taking their vehicle registration paperwork to the office with him in the morning and returning home at night with their new license plates.

"The people in Fish Lake Valley don't call the office. They call my house," he says.

AN EDUCATION

Multitasking is also an important skill for school district employees.

When one of the county's six certified teachers broke her hip last year, the superintendent wound up teaching fourth-grade math for several months. Aumaugher also has been known to drive a school bus on occasion.

"We have to make do," he says.

This is nothing new for him. He has devoted his entire 39-year career to rural schools in remote districts.

Before coming to Goldfield four years ago, Aumaugher was the superintendent of Eureka County.

And he got his start in the 1970s as a teacher in Garfield County, Mont., which just might be the only county in the lower 48 with fewer residents per square mile than Esmeralda County.

"I'm looking forward to retiring and living near a Walmart," Aumaugher says.

The district holds classes four days a week to save money.

Overcrowding is not an issue. This past school year, there were 39 students in Fish Lake Valley, 18 in Goldfield, and Silver Peak had no students at all in three of its nine grades.

Yet thanks to grants and donations, Aumaugher insists the county's classrooms are among the most technologically advanced in the state.

For the high school students who must spend as much as three hours a day riding to and from Tonopah, the district uses federal grant money to equip their bus with laptop computers and an onboard tutor.

The same grant also pays for a special activity bus so Esmeralda students can stay late and participate in extracurricular activities at their high school in Nye County.

Even Scates' room in the district's smallest school sports a state-of-the-art electronic white board on which he can project his lessons using a handheld computer pad. It also has a row of PCs that were donated by the U.S. Department of Energy.

"We have a lot of technology for a class this size," the second-year teacher says. "Being as poor as we are, people like to give us things, which is nice."

While Scates works with the older kids in one room, his wife, Rina, teaches the younger ones in the room next door. Their 2½-year-old daughter, Delia, roams back and forth between them, absorbing everything.

Rina is a certified teacher just like her husband, but she technically works as his classroom aide because that's all the district can afford.

The couple moved to Esmeralda County two years ago after they saw the district's job listing on the Internet.

Scates says Rina had a good-paying job as an attorney with a prominent Chicago law firm, but they decided to get their teaching degrees and move somewhere in the West where they could explore the outdoors and raise a family.

"We were looking for an exit strategy to get away from all those hours and all that money," Scates says with a smile. "What better way than to go into education?"

Now, instead of an apartment in the city, they pay cheap rent on a district-owned house on the hillside just above the school.

"Our quality of living out here is a million times better," Scates says. "I don't feel like we gave up much."

WHAT'S NEXT

To put it kindly, the county's economic development plan is in a state of transition.

For years, Gillum and other county officials openly defied state leadership by throwing their support behind the proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain.

The project looked like poison to others, but Esmeralda residents saw it as a way to bring back jobs and rail infrastructure.

With the repository now all but dead, the focus has shifted to the emerging alternative energy market.

Gillum says parts of the county show real potential for geothermal and wind-energy production. All they need are the transmission lines to carry that power out into the world.

Some infrastructure investment also could help fuel a comeback for the mining industry.

With the price of gold at a record high, Kirby says several mining companies have started exploring new deposits and re-examining old ones in the county, including the Mineral Ridge site in the mountains above Silver Peak.

There is even talk of a private investor with grand plans to reopen the historic Goldfield Hotel, though residents have heard such rumors before.

"We get a lot of anticipation out here that never bears fruit," Kirby admits. "But I think our population is going to come back, and I think it's going to come back because of mining."

If that doesn't pan out, they can always count on history buffs, amateur prospectors and eccentric old desert rats.

Gillum says Esmeralda County will never lose its appeal to people like that.

"If they're like me, they'll love it here," he says. "Even if they have to haul their own water or generate their own electricity, they'll come."

In the meantime, John and Rina Scates are doing their part to reverse the county's decline. On May 22, they welcomed a new baby girl into the world.

Aven Scates measured 8 pounds, 14 ounces and 22 inches long, and with her arrival, the population of Silver Peak ticked up one full percentage point.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.