Initiatives tackle food waste in Southern Nevada

This scene plays out repeatedly in Las Vegas: Hundreds of people stream out of banquet halls and ballrooms, leaving behind mounds of uneaten food — hundreds of pounds of mashed potatoes, meatballs, dinner rolls and fancy desserts. Blocks away, stomachs rumble and ache from hunger pangs.

MGM Resorts International this year awarded a two-year, $768,000 grant to Three Square food bank to retrieve and redistribute unserved food from professionally catered events at three of its properties: Aria, Bellagio and occasionally Mandalay Bay. The money pays for employees, trucks, gasoline, freezers and other equipment needed to transport the food. The program grew out of a smaller initiative that began in 2016 at Aria.

“It proved to be extremely successful, which led us to say if we can do this at one property, let’s see if we can expand,” said Phyllis James, chief diversity and corporate responsibility officer for MGM Resorts International.

In its first year, an estimated 56,000 meals were “rescued,” according to James, instead of being thrown away or used as animal feed.

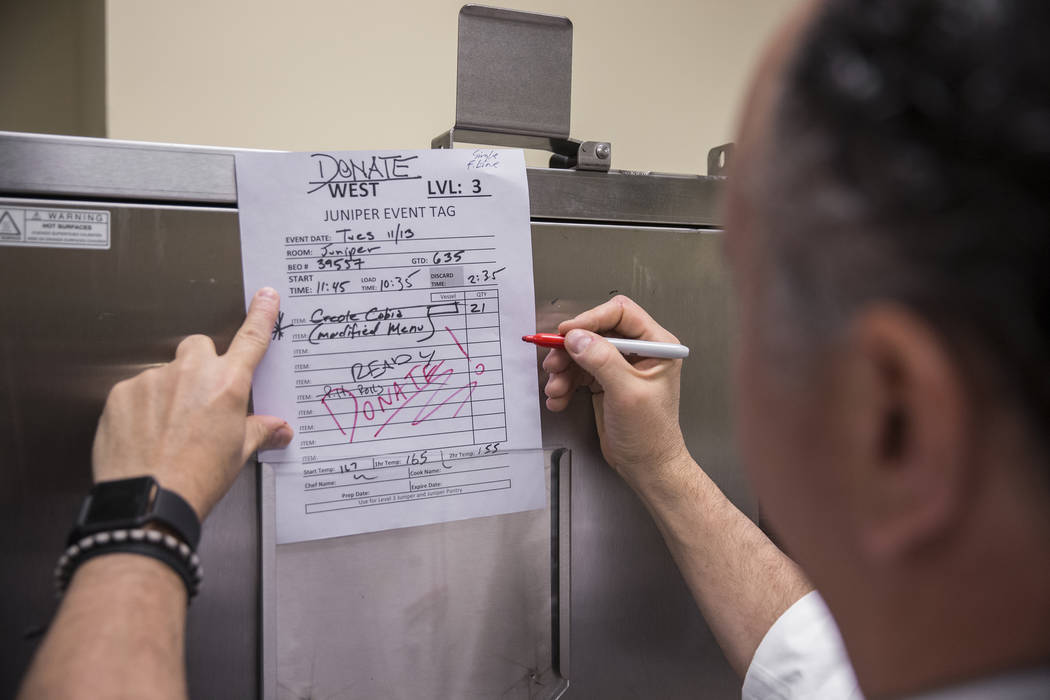

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, three Three Square workers walked quickly into a service area behind a ballroom where a luncheon for 3,000 guests had just ended. In a well-choreographed routine over the next two and a half hours, they filled aluminum trays with herbed chicken and potatoes, baseball-sized meatballs in marinara sauce, grilled fish, gnochetti, penne and vegan cannelloni. One by one the trays were slid into stainless-steel warming cabinets that would keep the food hot for the trip across town. After recording the foods’ temperature, crimping on lids and labeling each pan, the Three Square team loaded them into the hot boxes and into a waiting 26-foot box truck.

In all, the team collected 157 pans — about 785 pounds — of food to redistribute.

Then it was back to Three Square headquarters, 12 miles away in northeast Las Vegas, where the pans would be unloaded, temperature-checked again and moved to a blast chiller that would cool the food to 41 degrees in about 30 minutes. Food later would be moved into one of two 2,200-square-foot storage freezers and await pickup by the food bank’s member nonprofits. Agency representatives consult a computerized listing to find out what’s available and when it was acquired and can purchase it for 19 cents a pound for meats and other proteins, 9 cents a pound for other food.

One such agency is Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada, whose 16 programs and services include Meals on Wheels, the St. Vincent Lied Dining Facility and a food pantry, all dedicated to feeding hungry people.

Deacon Tom Roberts, Catholic Charities president and CEO, said the Meals on Wheels program serves more than 2,000 seniors daily, with 700 on a waiting list. The dining facility serves 1,000 meals a day.

“This may be the only meal of the day that they get,” he said. “Every day we get sincere thank you’s because they’re so grateful. People are coming here because they’re scared and frustrated and embarrassed.”

The food-rescue program might not be the sole answer to the city’s hunger problem, but because there are so many large convention centers and hotels, its hunger-fighting effect could be substantial, he said.

“This sort of pilot test will give us the knowledge to build a thoughtful model,” he said. “This program is not a silver bullet, but I think it’s a legitimate way to address food insecurity.”

Larry Scott, chief operating officer of Three Square, said the food bank rescues 13 million pounds of supermarket food each year at a cost of about 9 cents a pound, while the prepared-food rescue costs about $1.25 a pound because of food-safety standards. For that reason, he said, the prepared-food rescue program would need to be subsidized — by grants or financial donations — for it to grow.

But the potential is huge, if all of the companies that have banquet facilities were to join the effort, he said.

“By itself, we could potentially fill the meal gap that we still are chasing,” he said. While Three Square provides 38 million meals a year, 10 million more are needed.

“This is one of our best sources of meat proteins,” he said. “It’s a unique type of rescue that’s so needed. We can get peanut butter, but people need meat periodically, too.”

“Globally,” he said, “it’s a terrible tragedy to think that we waste 40 percent of our food and leave 15 percent of our population hungry. That simply has to stop.”

One young observer of the food-rescue program is impressed. Three Square’s Zev Klein said his 6-year-old son, Conner, recently said he wanted to do what his dad does when he grows up.

“You mean be a truck driver?” Klein asked.

“No,” the boy said. “I want to feed hungry people.”

Contact Heidi Knapp Rinella at Hrinella@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0474. Follow @HKRinella on Twitter.

Buffet leftovers

Leftover food from buffets, unlike unserved food from banquets, cannot be recovered because of food-safety standards.

"Food that's been offered to the public for service has the potential for contamination by the customer," said Larry Rogers, environmental health manager for food operations with the Southern Nevada Health District. "You can have one sick patron that can cause a whole group to be sick. You lose an element of control once it's been out for service. It's best done only when the food is handled by knowledgeable staff."

The limited exceptions, he said, include single-service prepackaged foods, crackers commonly found on salad bars and food in containers that limit contact, such as ketchup and hot-sauce bottles.