Lincoln Highway’s centennial draws a crowd from Europe driving classic cars coast-to-coast

ELY

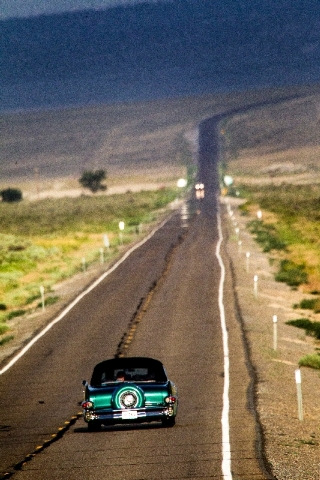

Arild Kolnes’ 1958 Cadillac convertible hums westward up the mountain and out of this central Nevada mining town.

Within minutes, the comparatively bustling city, with its handful of neon-lined hotel-casinos and population of about 4,300, gives way to giant rock faces dotted with juniper and cedar trees, expansive valleys and very few people.

The two-lane route, U.S. Highway 50, has been dubbed America’s Loneliest. But its other, older name drew Kolnes from his native Norway to the open road.

Highway 50 is part of the Lincoln Highway, America’s first paved transcontinental path, and it has been drawing motorists for 100 years. The celebration of its centennial has attracted sightseers and history buffs from around the globe.

Kolnes was in Nevada in late July with a caravan of 80 classic vehicles that included a ’48 Chevy Fleetline, a pair of ’58 Buick limited convertibles and a 1956 DeSoto Indianapolis 500 pace car. The cars were made in America, but they now live in Europe. Their drivers hailed from Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Germany.

From throngs of tourists in Times Square to blueberry pie at Great Plains cafes and Western scenes of dusty ghost towns, the road trip offered a slice of Americana, more than 3,000 miles long.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime journey, I would say, to see America from a classic American car,” Kolnes said, the sunrise dancing in his rear-view mirror. “It’s been a pleasure.”

‘ROCK HIGHWAY

A century ago, long-distance drives weren’t so pleasant.

Most roads were more hiking trail than highway, dirt tracks offering a washboard ride or a muddy mess. Many lacked road signs, so it was easy to get lost.

Most people traveled by train.

Lincoln Highway mastermind Carl Fisher wanted to change that. The early automobile enthusiast, headlight manufacturer and Indianapolis Motor Speedway developer believed folks would drive farther if they just had good roads.

When Fisher started pitching an innovative “rock highway” from the East Coast to the West, America had more than 2 million miles of rural routes but fewer than 200,000 miles of improved surfaces, often gravel, shell or brick. None of the roads, improved or raw dirt, connected to form an interstate highway.

In 1913, Fisher asked his auto industry friends for donations to improve existing roads to form an automobile route from New York to San Francisco. Anyone could join his highway group for $5; and he expected cities and towns along the way to provide material and labor.

His coast-to-coast super road, named for President Abraham Lincoln, would cost $10 million.

An effort to map the route took 34 days to get from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Construction was slow going, too. By 1914 some dirt work started, but it would be 1920 before Indiana laid down an “ideal section” of 40-foot-wide, 10-inch-deep concrete.

A 1916 travel guide for the Lincoln Highway advised trekkers to wade water before fording, bring an ax and wear old shoes.

One other bit of advice for the Nevada leg still worth noting: gas up often.

CLASSIC GAS GUZZLER

Nearly 80 miles down the road in Eureka, Kolnes rolls into a Shell gas station to heed that advice .

Kolnes is not sure how many miles per gallon he is getting because the Caddy “likes gas” and the needle is moving left at an impressive clip. He doesn’t want the 20-gallon tank to run dry in the 70 miles that separate Eureka and Austin.

To get to the green Caddy’s filler spout, he squats down level with its whitewall tires and lowers the driver-side taillight to let it drink.

Kolnes, 51, works in offshore oil drilling, a constantly modernizing business, but he appreciates old things, particularly an older America. Eureka’s a good place for that. Its Main Street, aka Lincoln Highway, is a throwback, with an opera house, a bed-and-breakfast and a rustic wood-front casino.

When he was a kid, Kolnes’ aunt and uncle moved to Chicago. On visits home they always brought exotic gifts: Juicy Fruit gum and magazines about cowboys and Indians, which fueled his love for the TV Western “Gunsmoke,” with Norwegian subtitles.

Perhaps the aunt and uncle’s biggest influence, however, were their American cars.

For everyday business Kolnes might drive a European car, such as a Volvo. But like many Scandinavians his obsession is the American classic car. He’s a member of the international ’58 Cadillac owners’ group, and he works on a publication for the Norway branch. His garage holds a 1968 Camaro, a 1964 Chevy C-10 pickup and that big, thirsty Caddy.

During his time off from North Sea oil rigs, Kolnes rebuilt the convertible “from scratch” over nearly 10 years, replacing the motor, rusty side panels and a floorboard full of holes. The only things he sent out for were the leather interior, chrome coating and the final paint job.

For Kolnes, American cars embody style and power. The Lincoln Highway is simply their native habitat.

PATRIOTISM ON PARADE

This trip isn’t cheap. Organizers said the bill to ship 80 cars from Europe, and to pay for hotels and meals runs $15,000 to $17,000 per car.

But Kolnes wouldn’t have missed it. He loves seeing American patriotism, whether it’s star-spangled shirts or hearing “God Bless America.” In his country, he said, citizens are more reserved.

“America was there when we needed them back during the second world war,” Kolnes said. “Norway has always had a good relationship with America.”

With another $50 of gasoline in the tank, Kolnes wants to be back on the road, chasing the sun to the horizon. But several fellow travelers want to stretch their legs a bit longer in Eureka.

One is Henrik Bjorklund, a Swede who rocks an Elvis Presley pompadour he has had for almost 20 years. That day he even donned a white T-shirt to go with his jeans. He wore wooden clogs, a Swedish tradition, and also good for driving his 1959 Chrysler Imperial.

Bjorklund likes the classic look: fins and chrome on the car, long sideburns on the driver.

The 47-year-old feels the same about meandering backroads. On long, straight freeways you zoom past interesting sights.

But does he sing like Elvis?

“Maybe when I have a couple of drinks.”

MARKETING TOOL

Years after the Lincoln Highway was established, Nevada tourism officials turned the pejorative “Loneliest Road in America” into a marketing campaign.

Even in these paved days, cars on the road and buildings alongside it are scarce. On an average day, fewer than 600 vehicles pass through Eureka on Nevada’s portion of the Lincoln Highway, which travels through tough terrain and is two-lane everywhere east of Carson City.

But in early Lincoln Highway days, it was low, flat country and not steep mountain climbs that earned the most notoriety. A little rainfall on the usually dry, cracked playa between Eureka and Fallon turned fine silt into thick mud. That’s a recipe for stuck and sunken vehicles, and it happened plenty.

A California woman kept a diary of her 1914 drive with her husband across the Silver State. The Nevada Historical Society magazine reprinted the account in 1991.

Paula Davis described the area east of Fallon as “ ‘absolutely impassible’ when it rained,” and doubted the entire state had 50 miles of graded road.

Her plight wasn’t unique. The Lincoln Highway covered the Overland Trail for stagecoaches and wagons, and also the same path for the Pony Express.

“It was the worst section of the Lincoln Highway on the continent,” said Jim Bonar, Nevada’s representative on the Lincoln Highway Association.

The group promotes preservation and awareness of the highway.

Things got better when the feds got more involved, Bonar said.

What would later be christened Highway 50 in the U.S. numbering system was soon raised five feet for a length of 11 miles through the playa Davis despised.

“That was the first major road repair to improve any kind of major highway in the state of Nevada,” Bonar said.

CENTENNIAL TOUR

These days, ambitious drivers can traverse 13 states on the Lincoln Highway in about the same time it took the Davises to drive across Nevada alone.

“You could do it in seven days, but you’d be pretty tired,” said Kay Shelton, national president of the Illinois-based Lincoln Highway Association. “Two weeks is good.”

That’s about how long the official Lincoln Highway Association centennial tour took in June. Part of that group set out from Lincoln Park in San Francisco, while the others left from New York. They met in the middle, Kearney, Neb.

At least 17 other groups, including a band of antique travel trailer devotees and another with deaf motorcyclists, have notified the association about their commemorative trips this year.

Lincoln Highway isn’t as famous as Route 66, although it’s more intact than its more famous cousin. A catchy jingle — “(Get Your Kicks) On Route 66” — with lyrics describing stops along the way is a pretty helpful marketing tool.

But Lincoln Highway isn’t totally left out of popular culture, Shelton said.

“On the Road,” Jack Kerouac’s ode to the Beat Generation, includes many Lincoln Highway scenes, although it’s not mentioned by name, she said.

U.S. Highway 50 is also featured in “The Long, Long Trailer,” a 1953 film starring Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

Shelton hopes the highway’s 100th anniversary will make it more prominent as a snapshot of U.S. history and scenery.

In Pennsylvania the road goes right by the memorial for Flight 93, near Shanksville, where passengers crashed a hijacked Boeing 757 to prevent terrorists from crashing it into Washington.

The road also can get travelers to Gettysburg, site of the crucial Civil War battle.

Out this way, the Lincoln Highway rounds the south end of Lake Tahoe, offering world-class windshield views.

MIDDLEGATE STATION

As the European drivers pull out of Austin, a vehicle loses a rear axle. Another difference between now and 100 years ago: These travelers have backup.

Organizer Henning Kjensli has three support vehicles loaded with tools for roadside fixes and winches to tow cars needing more extensive work. The arrangements came in handy in New York, where an engine overheated; in Indiana, where a motor needed replacing; and in Illinois, where a car crashed into a guardrail.

Most of the classics on his trip are equipped with GPS systems, Kjensli said, but “other than that there’s not too many modern aids.”

But GPS and cellphones don’t always work in remote areas. Since Lincoln Highway has lots of that, Kjensli and other service vehicle drivers stay near the back of the pack to spot any stragglers.

Farther west, some drivers stop at Middlegate Station, a family-run roadhouse that includes a bar, rustic hotel and plenty of T-shirts and hot sauce on sale.

Travis Anderton is behind the counter making up a batch of meatloaf burgers and ready to serve up a quip about passersby.

Middlegate’s address is Fallon, but the 27-year-old is quick to point out that he had a 47-mile commute each way into town for school.

Highway 50 isn’t as lonely as it was when Anderton was a kid. In the mid-1990s, his mom could finish a whole crossword puzzle without having to look up to see whether anybody was coming down the driveway.

But this year business is brisk, and he has seen dozens of classic cars and the occasional Jaguar or Porsche glide in.

And not everyone sees Highway 50 through a windshield. One day his uncle spotted a man on foot, pushing a 10-foot cross on a wheel. Another time a fellow rode a bicycle backward down the road.

“I’m waiting for the guy on the Pogo Stick next,” Anderton said.

Anderton isn’t quite sure what has driven the increased traffic.

The Nevada Highway Patrol may have noticed, though. In response to four fatal crashes in three months, the agency promises stepped-up enforcement on Highway 50 through Aug. 12, looking for motorists who are speeding, drunk, high or — if they can actually ping a cell tower — talking or texting.

ROAD TRIPS

The road trip, whether a coming-of-age jaunt or a respite from the workweek, is ingrained in American culture. It’s about adventure, whether we’re talking freedom-seeking and ultimately tragic Thelma & Louise in the 1991 movie, or the siren song that defined a restless generation in Kerouac’s 1957 masterwork.

Even “The Hangover,” exploiting Las Vegas glitz and glitter, starts with a road trip through the Mojave Desert.

The national fascination with long drives through empty spaces — and the high-speed roads that made them possible — was born on the Lincoln Highway in 1919.

That was the year the War Department wanted to test the Army’s ability to shift troops from coast to coast in wartime. A convoy of 80 trucks and a small tank clattered from Washington to San Francisco, often on the dirt track that would one day become Highway 50.

Like everyone else, the soldiers got stuck in mud and delayed by breakdowns during the two-month trip.

The point of the expedition was not lost on one of its young officers, Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower. A hallmark of his presidency, four decades later, was creation of the Interstate Highway System. It was pushed through Congress as a national defense program, not assistance to truckers and vacationers.

Lots of us fly down freeways every day; many behind the wheel. What transforms the act of driving into the experience of a lifetime?

“It’s mostly a switch in your brain,” said professional road-tripper Mark Sedenquist. “You can travel the same road to work, but you can do it in a slightly different way.”

That can mean taking a less-traveled route or scoping out signs or restaurants you don’t normally look for, said Sedenquist, who with wife Megan Edwards runs Las Vegas-based Road Trip America, an online trip planner.

For longer trips, they said, set a destination. But if you get an inkling, take a side road and see where it goes as you ride toward the horizon.

LONG STRETCHES

On Nevada’s share of Highway 50, the classic cars log their second-longest leg of their monthlong odyssey.

Drivers clock 320 miles, give or take a few for taking a gander at Sand Mountain, or 35 or so if they chose the alternate route through the state capital before heading up to Reno.

(The longest stretch was 360 miles in Wyoming, from Cheyenne to Evanston.)

They end the night at a Nevada superlative, the Biggest Little City in the World, and many disappear into the mirrors, chandeliers and ding-ding-dings of the Eldorado casino.

The road will be there in the morning.

Contact reporter Adam Kealoha Causey at acausey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0361.