Creech Predator crews get help coping with combat

INDIAN SPRINGS — Water spills down a Plexiglas pane the size of several big-screen TVs inside the Airmen Ministry Center at Creech Air Force Base.

"We call it our decompression wall. It's a more passive way to decompress," said Chaplain Zac, a captain in the 432nd Wing. For security reasons and to avoid becoming a terrorist target, he can only identify himself by his first name.

The wall is one of the tools that he and other members of the "human performance team" use to help Creech airmen cope with their combat roles so close to home. The team members have top-secret security clearances "to be with our folks where they work," he said.

Like people who relax by watching fish swim in an aquarium, the airmen who fight the nation's war from afar with remotely piloted aircraft — better known to civilians as Predator and Reaper "drones" — often stop by the center to unwind by the wall, and play pingpong or shoot pool.

Some even try their hand at video games despite the routine of their profession.

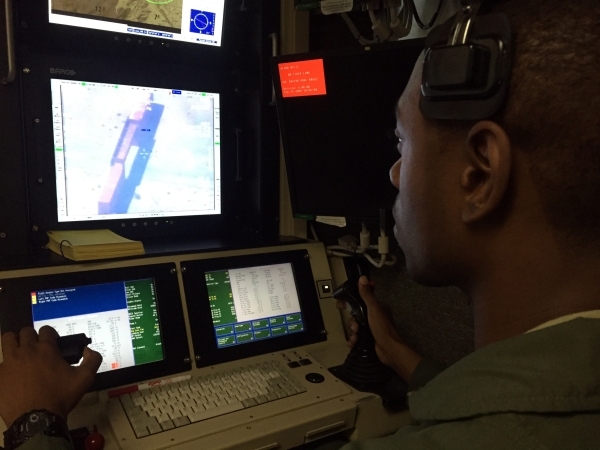

For these pilots and sensor operators, the war-fighting task involves sitting long hours at computer consoles, gripping joysticks to control the flight of an aircraft, scan the landscape with high-tech cameras, or hold laser beams on targets by way of satellite-link signals half a world away.

Once in a while they will pull a trigger to send a Hellfire missile or a laser-guided bomb hurtling through the sky to destroy an insurgent's hide-out, knock out an enemy combatant's vehicle or stop "bad guys" from planting roadside bombs designed to kill U.S. troops.

Critics of drone strikes point out that innocent civilians sometimes die in the attacks. And, there was a friendly fire incident in 2011 involving a Predator missile strike triggered from Creech that left a U.S. sailor and a Marine dead in Afghanistan.

With the nature of remote-controlled warfare comes a daunting task for Chaplain Zac's team: Find "healthy ways" for the airmen to transition from the war zone to the home front 45 miles away in Las Vegas.

Fighting war from afar

At a base media briefing this summer, former 432nd Wing commander Col. James "Cliffy" Cluff summed it up, saying, "Every single day this base is at war."

He said the wing's 3,325 "warriors" at Creech "are not kids playing video games in their mother's basement."

"These are professional airmen," Cluff said. "These are professional aviators and support personnel, and their job is to help fight America's wars."

The sobering reality of drone strike missions comes from hours of boredom, punctuated by sudden orders to engage targets, then survey the destruction and sometimes bloody aftermath. While the airmen aren't in harm's way, they still must cope with combat stress and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress disorder.

In an Aug. 6 interview, Chaplain Zac, his assistant, Sgt. Brad, and aerospace physiologist Maj. Meg talked about their unique roles to help the warriors of Creech adjust.

Much of stress comes from what is known in military circles as the "high ops tempo" coupled with a limited and dwindling number of trained airmen to meet the Pentagon's expectations.

"It's one of the realities of being successful," Chaplain Zac said.

The airmen are really good at what they do, he said, "and demand has outpaced our manning. So that issue is on the radar for everyone in the remotely piloted aircraft enterprise."

In January, Air Force leaders acknowledged that many pilots were leaving active duty to continue as Predator and Reaper pilots in the Air National Guard and Reserve. To avert a shortage in the active-duty ranks, the Air Force began looking at all options, including pay and advancement incentives, to "grow RPA professionals" and develop a career path for them.

Chaplain Zac pointed to a survey that found "our guys and gals feel" that most of the stress — 60 percent — is related to manning issues.

And while there has been a suicide and a case involving allegations of domestic violence blamed on post-traumatic stress disorder reported among the Creech airmen ranks this year, he noted that PTSD rates among remotely piloted aircraft crews remain at 2 percent to 4 percent, well below on-the-ground combat forces. Likewise, the Air Force suicide rate is "much lower than the general population in the United States, he said.

Coping with remote combat

About 500 airmen per month visit the base's ministry center, and the human resources team sees about 25 "counselees" per month. The operational psychologist spends about half of the 1,400 hours per month on "squadron-focused warrior care" for airmen.

Nevertheless, in addition to what is offered in recreational facilities and direct availability of human performance team members at the center, they hold "RACK" events, short for "Random Acts of Chapel Kindness."

"Maybe we'll bring in some food, or cater meals, or cook for them. But it allows us to lay eyes on the unit and get a pulse on the unit and the morale," Sgt. Brad said.

Chaplain Zac said sometimes it's a matter of "just letting them know it's OK to come in and take a knee."

"We look at these individuals the same as we would a professional athlete. They're highly trained. We're helping them understand what their limits are and perform their jobs in more of a marathon fashion instead of a sprint," he said.

Among civilian jobs, airmen in the RPA community have similar stress factors as law enforcement professionals, "specifically those who are involved in surveillance and apprehension," he said. "They work long hours of tedious boredom followed by life-and-death situations. And then they return home."

Any way you slice it, Maj. Meg said, "We are military people. We must be emotionally sound and mentally and physically sharp."

The long drive home

The difference between remote combat operations and boots-on-the-ground missions in a war zone is that RPA pilots and sensor operators are "going home the same evening and interacting with families and others who have no idea of what they've been through."

Sgt. Brad said the drive from Indian Springs to Las Vegas "can get pretty monotonous," so the base provides an audio library for airmen to listen to during the commute. Subjects include leadership material, spiritual material, fiction and nonfiction.

"It's kind of a time when your start to think about your day. It's just a healthy way to decompress and think about what's going on before your get back to your families," he said.

"We want our airmen to be their best and operate at their best, so that they are not only the best warriors they can be but also the best people they can be. It's the 'whole person' concept we want to improve upon.

"We want our airmen to realize their own resiliency, that ability to bounce back," Sgt. Brad said.

Maj. Meg believes the most effective way to deal with stress is to have a physical outlet that gives balance to the mind and body so they can grow strong together on all fronts: mental, physical, psychological and emotional.

"We want to take care of the whole person, not just for their time in the Air Force but for the time when they move on as well," she said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2

PREVENTING PILOT BURNOUT

Air Combat Command leaders in January said the Pentagon's goal to reach 65 Combat Air Patrols would be difficult to meet as more pilots who fly Predator and Reaper remotely piloted aircraft were leaving than the training pipeline could replace.

One CAP involves flying four drones in a 24-hour span to hunt high-value terrorists and other militant targets and strongholds and destroy them with laser-guided missiles or bombs. Three years ago, CAPs numbered in the 40s.

Pilots work eight-hour shifts flying three to five hours per shift, for five or six days a week. There is an "on-call" relief pilot on each shift, so the duty pilot can take lunch and restroom breaks.

Because pilots have been staffed at 85 percent of the manning level, commanders want their crews to fly 60 CAPs instead of 65, so that more potential instructor pilots can be sent to Holloman Air Force Base, N.M., to train replacements.

The goal is to graduate 43 percent more pilots next year, increasing from 280 this year to 400 in 2016, according to flightglobal.com, an international aviation industry website.