Homeless join advocates protest proposed Las Vegas camping ban

Homeless people — many of them from the city of Las Vegas’ Courtyard Homeless Resource Center — wore red shirts Wednesday morning as they joined a City Hall protest against a proposed ordinance that would make it illegal to camp or sleep downtown or in residential areas if shelter beds are available.

As soon as the event ended, they tossed the shirts, which had been given to them by the city, in the trash.

The mass discard was a symbol of their distaste for the ordinance put forward by Mayor Carolyn Goodman. The measure was introduced Wednesday and scheduled for discussion at a Nov. 6 meeting.

“The mayor has said this is about compassion. That’s ridiculous. There’s nothing compassionate about jailing and ticketing people for not having a home,” said Emily Paulsen, executive director of the Nevada Homeless Alliance, which helped organize the protest.

“We want the City Council and the mayor to pull this bill immediately,” she said. “If it’s not, we’ll be back.”

About two dozen people participated in the protest. About half of them were advocates for the homeless and affordable housing. The other half were homeless themselves.

They gathered outside as the council met inside and approved a motion by Goodman to bring the ordinance up for discussion and debate at the first City Council meeting in November, skipping a recommending committee meeting typically used when ordinances are introduced.

The homeless wore name tags during the protest Wednesday so the City Council would know their names.

“These are homeless friends,” said Merideth Spriggs with the nonprofit homeless agency Caridad. “This is who you’re sending to jail. This is who you’re going to give these $1,000 fines to. These are the faces … Please look at them, because that’s who you’re going to punish.”

The new bill is meant to target the influx of homeless people camping downtown and other residential areas, which has spurred public health and sanitation concerns, particularly near businesses and places where food is processed, officials said.

It’s also intended to encourage those people to use services provided at the city’s 24/7 courtyard or services provided at other nonprofits.

Paulsen said the bill would only increase mistrust between the homeless, law enforcement and service providers, create legal issues for the homeless and cost taxpayers if it results in more homeless people being jailed — money that could be better used investing in affordable housing.

The homeless people in attendance agreed.

“This is like the Keystone Kops. Human rights are being violated,” said Joe Boyd, who wore a pin that read, “Housing not handcuffs.”

Another homeless man, Chad Francis, said he has been homeless for about eight months after he lost his job and ID. He said he understood the city’s stance, but he thinks there is a better solution.

“We’re in the conundrum, I used to camp out on Foremaster, but the city removed those camps,” Francis said.

“I see the city’s point of view. If I was them, I wouldn’t want trash and urine on the streets, but I think legislation could be put in that could regulate that,” he said. “We can work together.”

Some homeless advocates say the ordinance is a moot point, as there are about 1,800 emergency shelter beds in Clark County that are often at or near capacity. Ninety-one percent of them were full the night of the county’s annual homeless census in January.

“I can’t see any way that an ordinance like this could be enforced fairly if it is even enforceable at all. The problems Southern Nevada and its homeless community members are facing cannot be solved with punitive policies, and criminalization is not a substitute for housing or services,” said Sherrie Royster, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada.

Since the ordinance was announced last week, more than 300 individuals and organizations have joined a coalition opposing the bill, according to the ACLU of Nevada.

In a series of posts on Twitter on Monday, Goodman said the ordinance was designed to help direct people to the courtyard, located on Foremaster Lane and Las Vegas Boulevard, and other nonprofit services “to connect those in need and help break the cycle of homelessness.”

“The city believes the ordinance will be a benefit to the homeless population, while at the same time protecting the health and safety of the entire community,” she wrote. “The city has always demonstrated compassion for the needs of the growing homeless population, understanding the public safety of everyone is a top priority.”

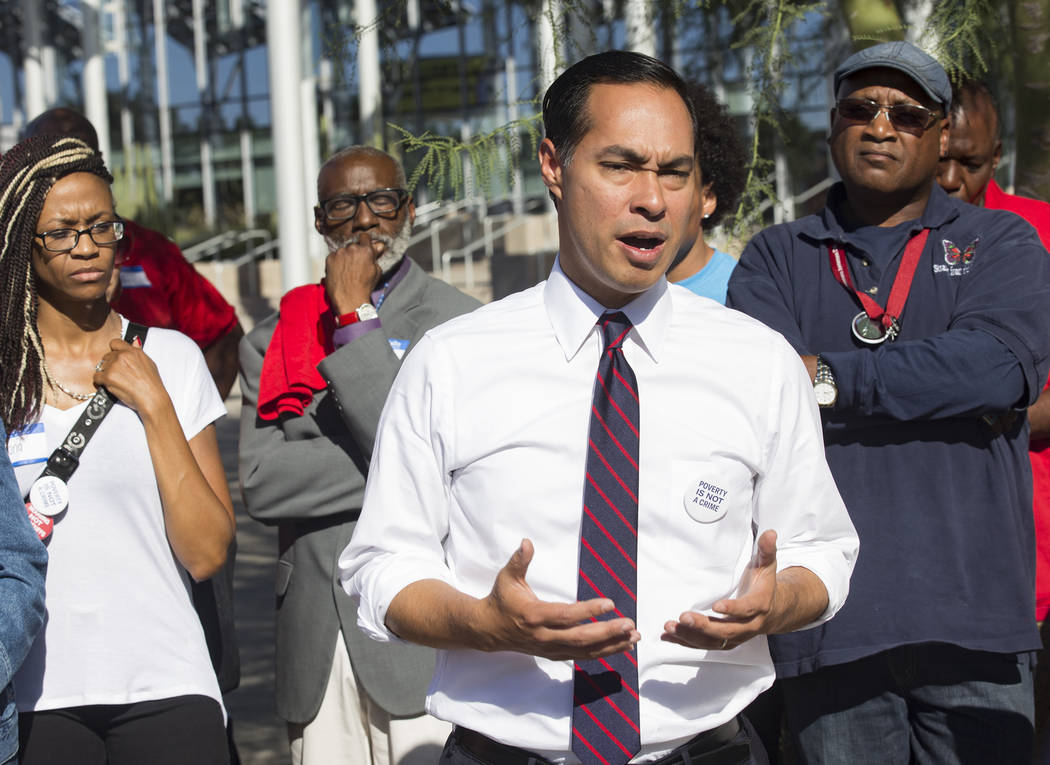

Among those attending the protest was former U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro, a Democratic candidate for president.

“To some people it may seem that if you get homeless folks out of sight, and perhaps out of mind, that that’s an improvement. But that’s a lie,” he said.

Castro previously served as mayor of San Antonio, Texas, whose courtyard for the homeless served as a loose blueprint for the Las Vegas facility.

He said Wednesday that he understands why some people choose not to seek shelter in a homeless courtyard.

“There are people that are afraid to stay in the courtyard. There are people with other needs that compel them not to go to that homeless courtyard,” he said. “You shouldn’t treat them like criminals. You should continue to work with them so they get their needs met.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.