Las Vegas officials plan ‘Corridor of Hope’ for homeless

Clustered at the edge of a bare lot at the northern reaches of Las Vegas are tents and makeshift shelters — tarps and blankets stretched across overturned bicycles and shopping carts — to give respite from the elements.

A man sleeps face-down on the sidewalk without so much as a scrap of fabric to rest his head on. Beyond him, a woman paces along Las Vegas Boulevard North and lets out frequent, pained cries.

This stretch of Las Vegas, dubbed the “Corridor of Hope,” is largely a scene of despair.

But the city is on the verge of rolling out a sweeping plan officials hope will be transformational: the pitch is to build a courtyard where homeless people can do everything from find shade to get on a path toward permanent residency.

“You can’t just move someone out if they don’t have a place to go,” Las Vegas Councilman Bob Coffin said. “This is the place to go. This is what’s been missing from the equation.”

The city’s plan

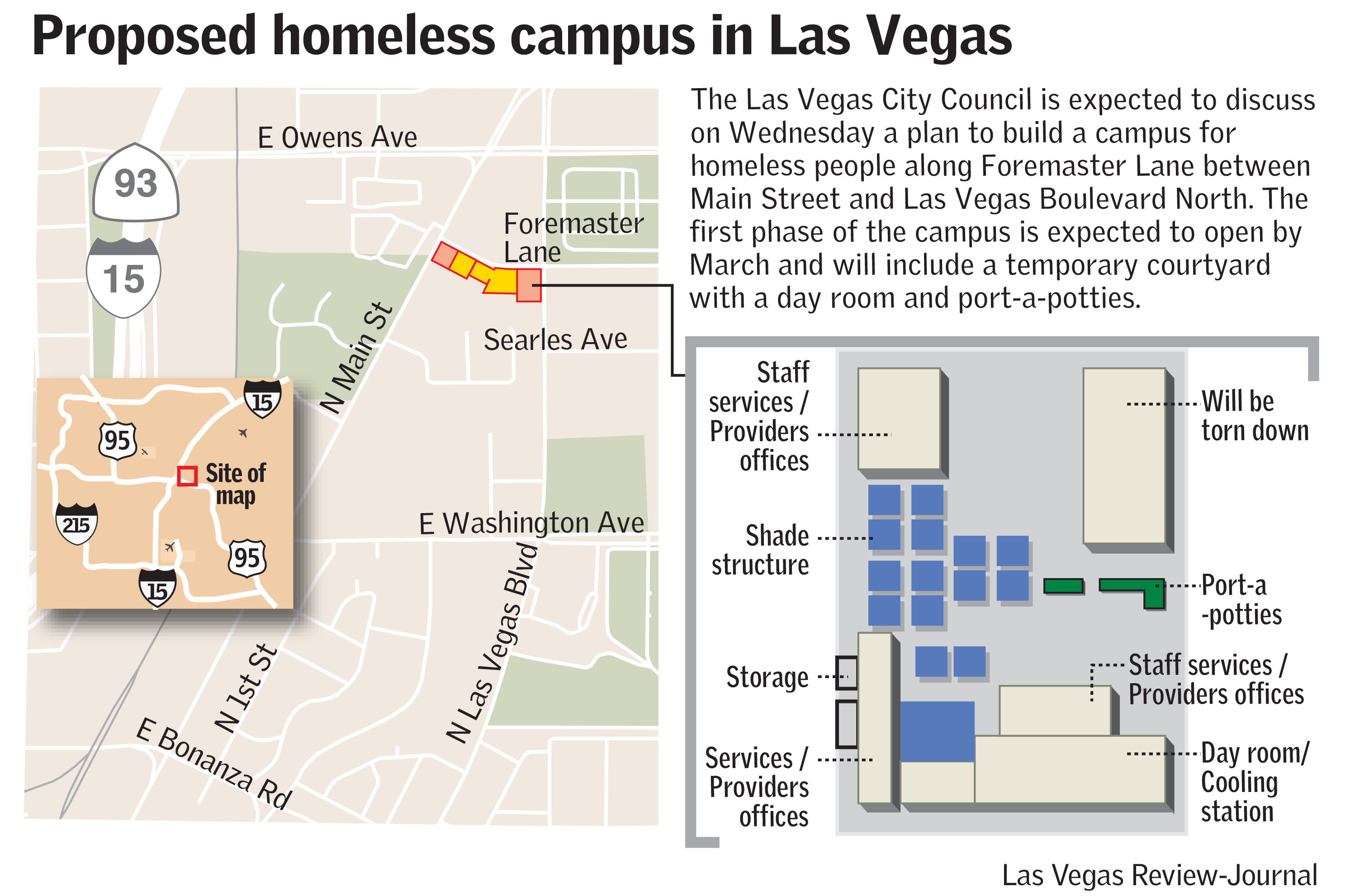

With an eye toward San Antonio’s integrated “Haven for Hope,” city officials have been acquiring land and accumulating funds to build something similar in Las Vegas along Foremaster Lane, across the street from Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada.

On Wednesday, the City Council is slated to discuss a plan to begin funding and building a courtyard to open by March 2018 that will offer temporary shade structures, portable bathrooms, storage containers and sleeping mats. A roughly $15 million campus would be built over the next two years.

Operating expenses are pegged at $1.5 million for the fiscal year that starts July 1, and will ramp up to $3.7 million in 2019-20. The city has funding lined up for the campus startup and build-out, but needs another funding source for operations beyond May 2019.

Wednesday’s council agenda includes a series of funding measures for the project. That would allow the city to put more than $7 million into next fiscal year’s budget for capital expenses and several months of operating costs for the planned March opening. The plan required reworking some of the city’s tentative budget for the next fiscal year.

“We’ve been working very hard for the past few years,” Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman said. “It’s time for action.”

The San Antonio model

The Las Vegas plan would follow the San Antonio model, which has drawn officials from other major U.S. cities with homeless issues.

The city of Las Vegas for years has tried to get people off the streets. Millions of dollars in stimulus funds were earmarked for homeless issues. A city ban on feeding homeless people in parks in 2006 gained national attention before it was shot down in court after the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada sued.

Compared to other large U.S. cities, Las Vegas, has a disproportionately large homeless population. The city not only lacks a cohesive approach to serving the needs of the homeless people, there is no place for the homeless to go during the day, or for those with drug and alcohol in their systems.

Those were some of the takeaways from the city officials’ study of cities like San Antonio and Phoenix, Deputy Las Vegas City Manager Scott Adams said.

“In the coming months I think you’ll see a much more aggressive approach as a city and a region,” Adams said. “It’s something we can’t keep kicking the can down the road on.”

Adams was in a group of 28 area officials — including representatives from Clark County, the district attorney’s office and judges — who traveled to San Antonio in February to learn from the city’s “Haven for Hope,” a one-stop shop with law enforcement and social service providers on a 22-acre campus just outside the downtown area.

“I wanted them to be able to see it, touch it, smell it, see that there’s another city that’s done this and it doesn’t matter the jurisdiction,” said Metropolitan Police Department Assistant Sheriff Todd Fasulo, who spearheaded the trip.

San Antonio’s campus is a joint-government project, while the Las Vegas plan is geared toward downtown. But if successful, the city’s initiative could become a model that could spur satellite facilities elsewhere in the valley, city officials said.

San Antonio’s Haven for Hope cost $100 million, with 40 percent paid by the city and county, and 60 percent from private investment.

The Las Vegas plan currently has no such deal yet, but private money is expected to play a role once the startup phase has begun. Community Development Block Grant funds, Emergency Solutions Grant funds and Redevelopment Set-Aside dollars will get the project started.

“Maybe if they see the success of it, they’ll help contribute to the continuing operation,” city Community Services Director Stephen Harsin said of potential future investors.

Corridor of Hope

The city owns properties along Foremaster Lane between Main Street and Las Vegas Boulevard North, which bookend two properties the city has identified as “areas of interest.” Clustered in that area are The Salvation Army, Catholic Charities, women’s and children’s shelter The Shade Tree and Genesis Apartments for homeless veterans.

The “Corridor of Hope,” also known as “the homeless corridor,” is host to widespread homelessness.

One issue is the “service-resistant” homeless — people who don’t seek help or shelter because of mental illness, addiction issues or other reasons.

San Antonio’s campus includes an area for the admittance of people with drugs or alcohol in their system, a feature Las Vegas needs, Adams said.

“They’ve got no other choice but to be on the street,” he said.

Initial plans for the Las Vegas campus include an area for those with drug or alcohol users, a day room, permanent mental health services and even a pet kennel.

The startup phase planned for a March 1 completion calls for a one-acre courtyard area that could hold 250 to 300 people. It also includes six armed security officers and 15 nonprofit homeless agency staff to manage the site.

When that’s in place, work would begin to build out the campus in 2019, adding laundry and shower facilities, a sick room, a pet kennel, a coordinated intake office, and medical, legal and dental mobile services.

Coffin and Las Vegas Councilman Ricki Barlow, who represent much of the city’s urban core, were part of the group that went to Texas two months ago. This week the two councilmen huddled with city staffers to finalize what Coffin calls an “emergency situation” that the council will discuss on Wednesday.

City officials have had conversations with the owners of the properties they’re interested in for potential expansion of the courtyard, Harsin said.

One is a vacant funeral home building along Foremaster, and the other is the CARE Complex, a nonprofit that works with homeless people. CARE operations manager Mat Ellis, however, voiced uncertainty about the city’s plans. The city owns property on either side of CARE’s, where the organization just held a ribbon-cutting on its revamped Foremaster facility, after more than $300,000 worth of upgrades, in March.

“I don’t have any of the answers, just a lot of questions,” Ellis said.

Harsin acknowledged “we’re still trying to figure out what that looks like” with the organization’s continued presence on Foremaster and the city’s interest in the property.

Deep-seated issues

With many emergency responses and Municipal Court cases involving homeless people, sometimes there’s a brief stay in jail, and then they’re back on the street, without attention to any underlying issues that may contribute to their homelessness in the first place.

Fasulo wants to see a separate booking facility, similar to San Antonio’s, in part to minimize people with low-level charges ending up in jail.

“We have services, but we don’t have enough of them and we don’t have them in one location,” Fasulo said. “Between the city and county, we don’t have anything that’s complete wraparound services. Oftentimes people need treatment, not to be sitting in a jail cell. That’s nothing more than a Band-Aid.”

Local officials know there’s a service-resistant contingent among the local homeless population, and that the outreach teams that are part of this initiative may need to make multiple attempts to encourage certain people to seek shelter or other services.

“The hope is that not only would they want to come in, but that they would look at adjoining health areas and begin a road to rehab,” Goodman said. “That’s what we’re driving toward.”

Contact Jamie Munks at jmunks@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0340. Follow @JamieMunksRJ on Twitter.

"Corridor of Hope"

2017-18: Site preparation begins in July, which a target launch date of March 1, 2018. Operations include security, porta potties, temporary offices and shade structures, a homeless outreach team targeting people downtown. Proposed capital expenses: $4.4 million, operating expenses: $1.5 million for the fiscal year that begins July 1.

2018-19: Design of a permanent facility begins with offices, bathrooms, showers, laundry facilities and expanded services. A second homeless outreach team is added. Proposed capital expenses: $1.1 million, operating expenses: $2.98 million.

2019-20: Construction of permanent facility. Proposed capital expenses: $8.8 million, operating expenses: $3.7 million.