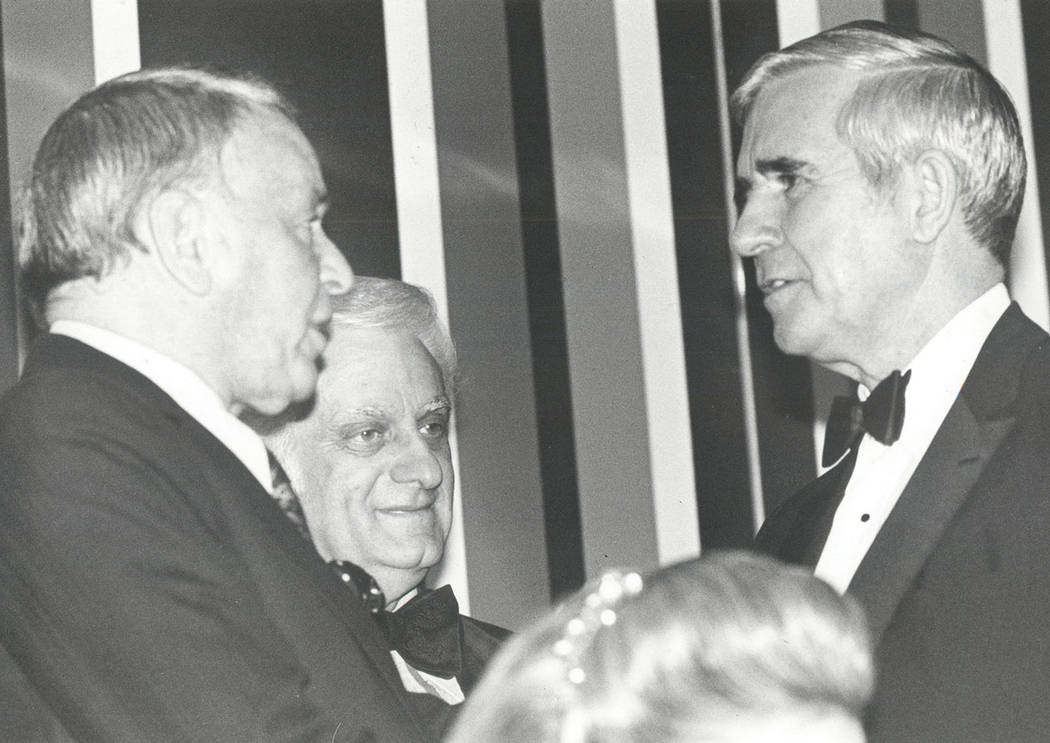

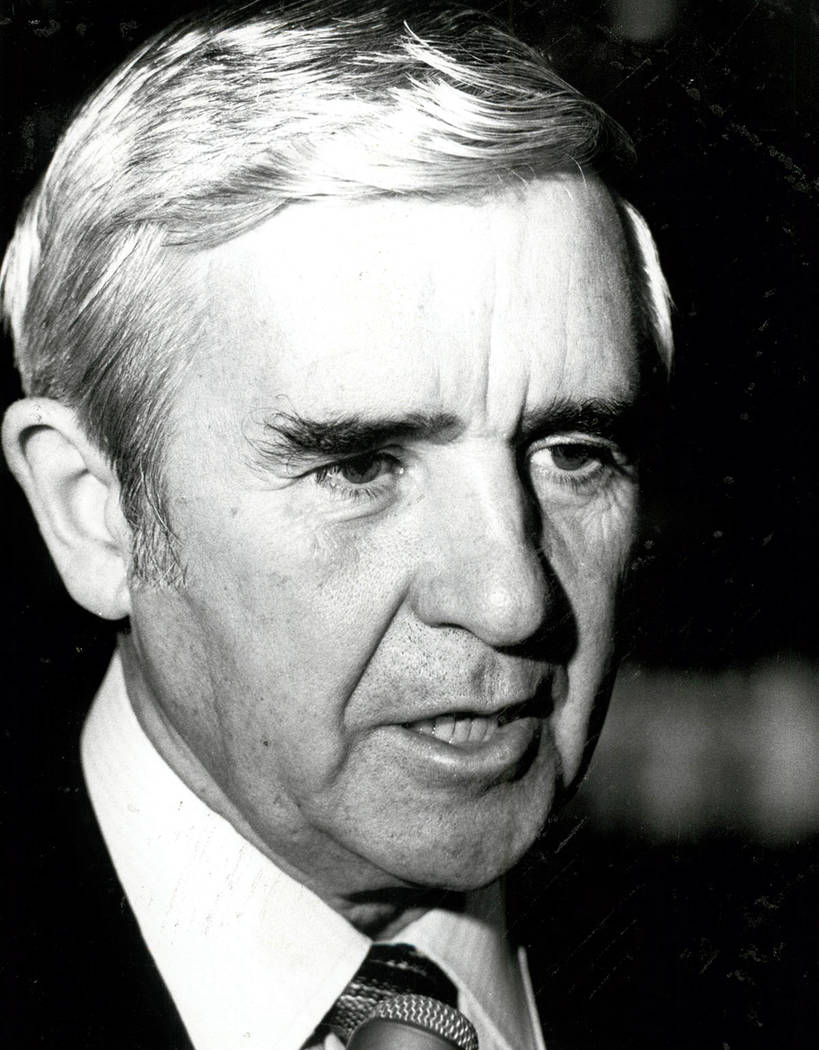

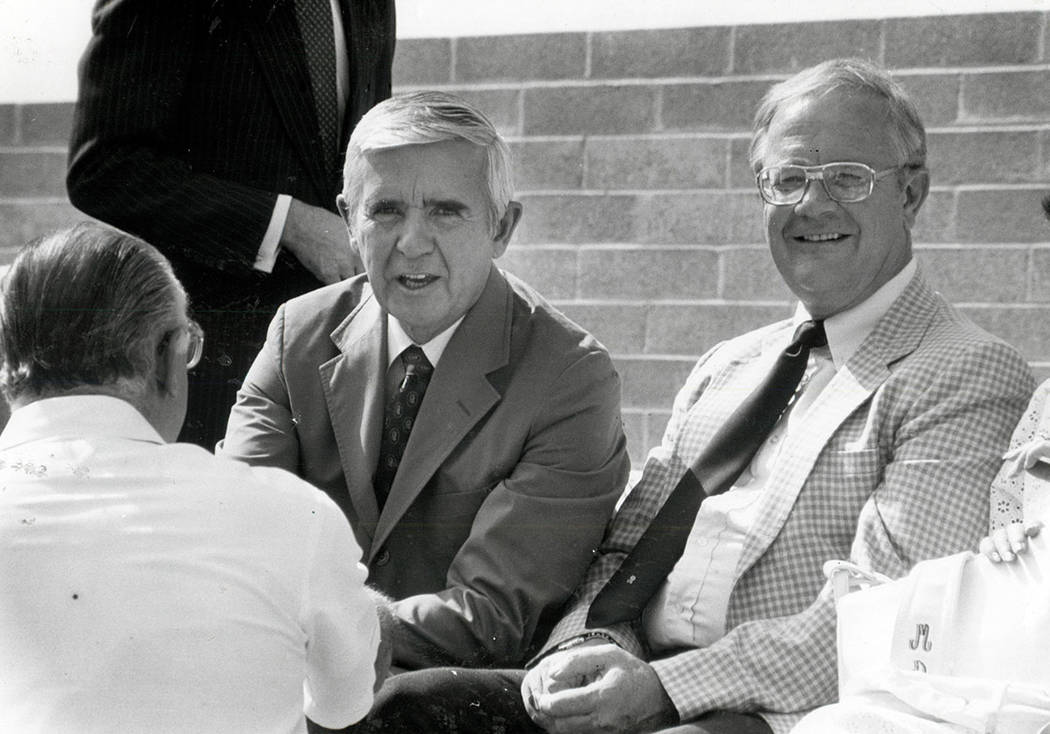

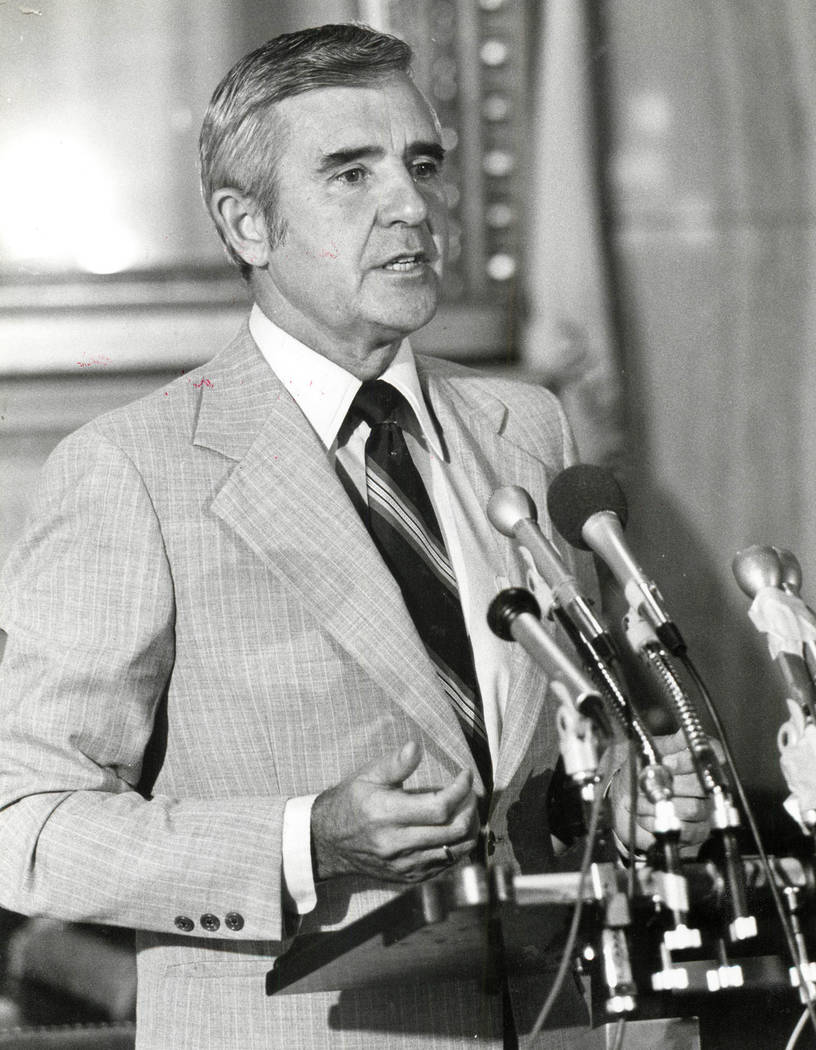

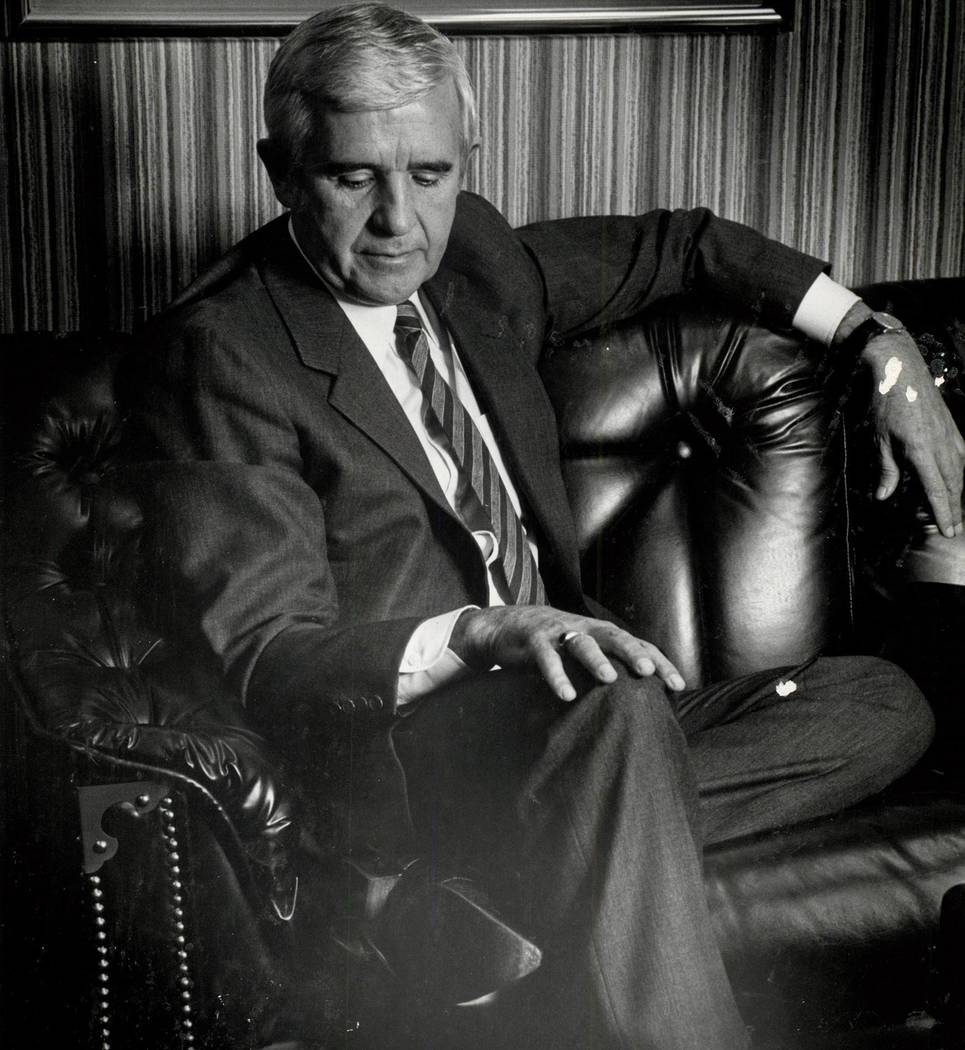

Paul Laxalt, former Nevada governor, senator, dies at 96

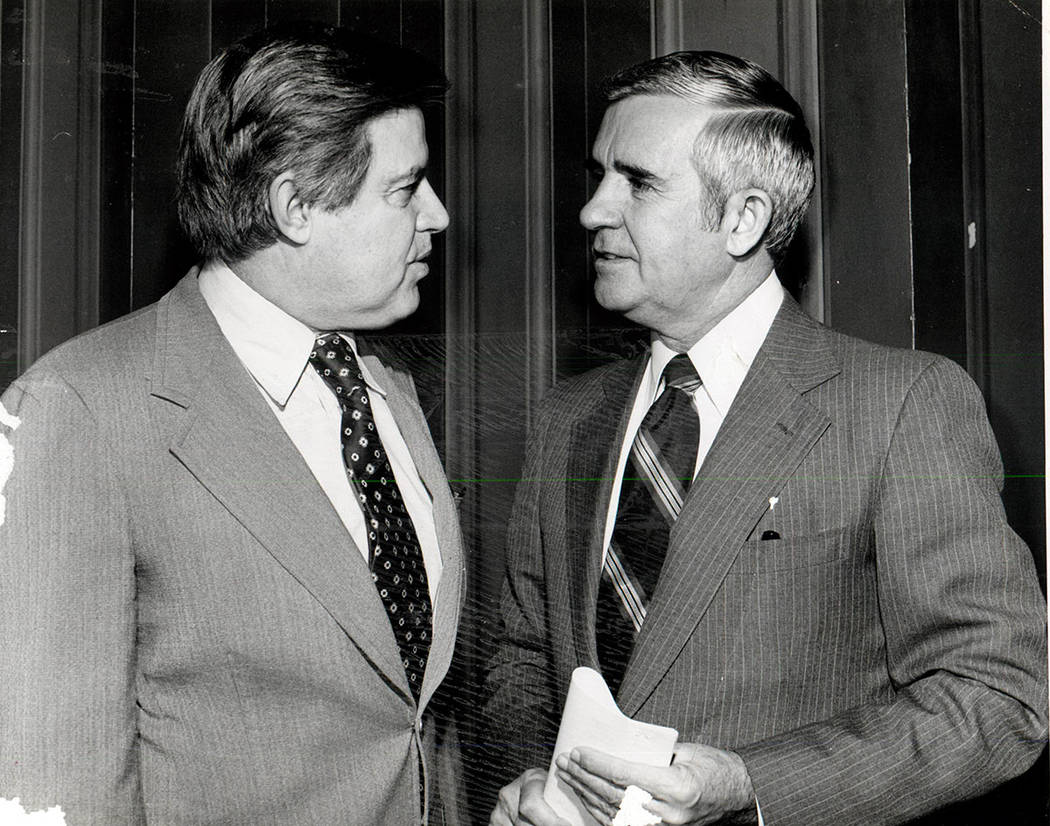

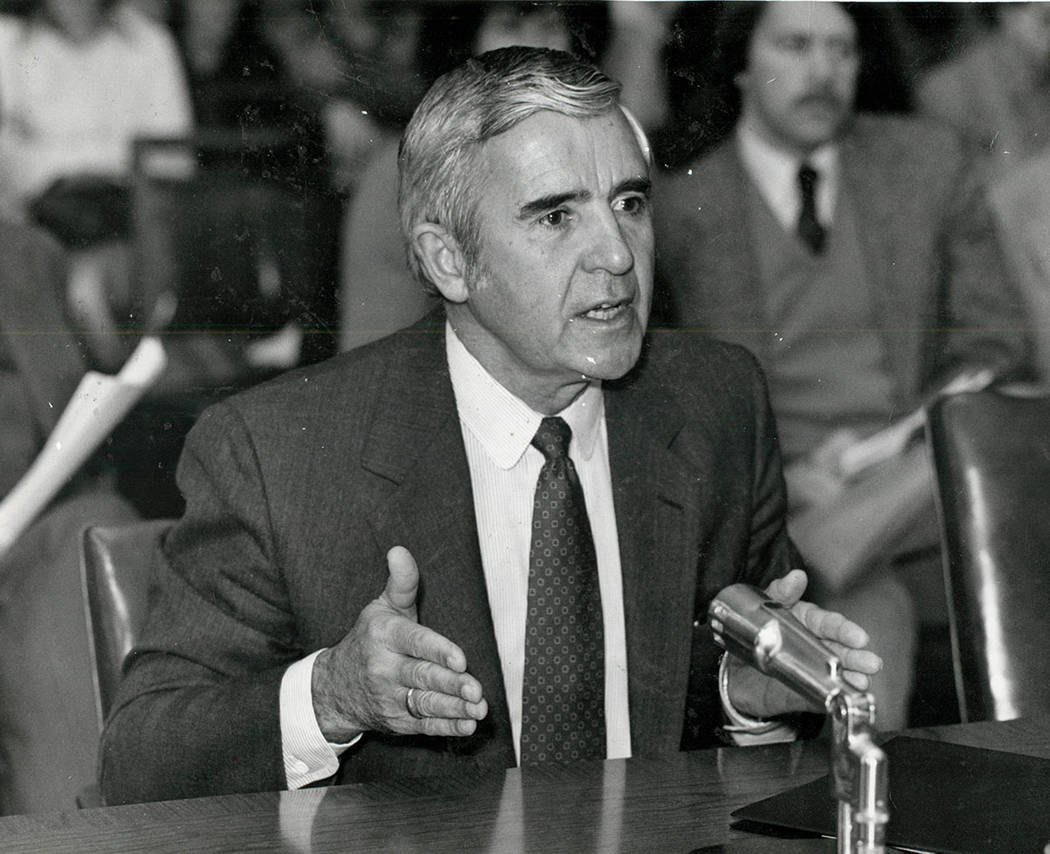

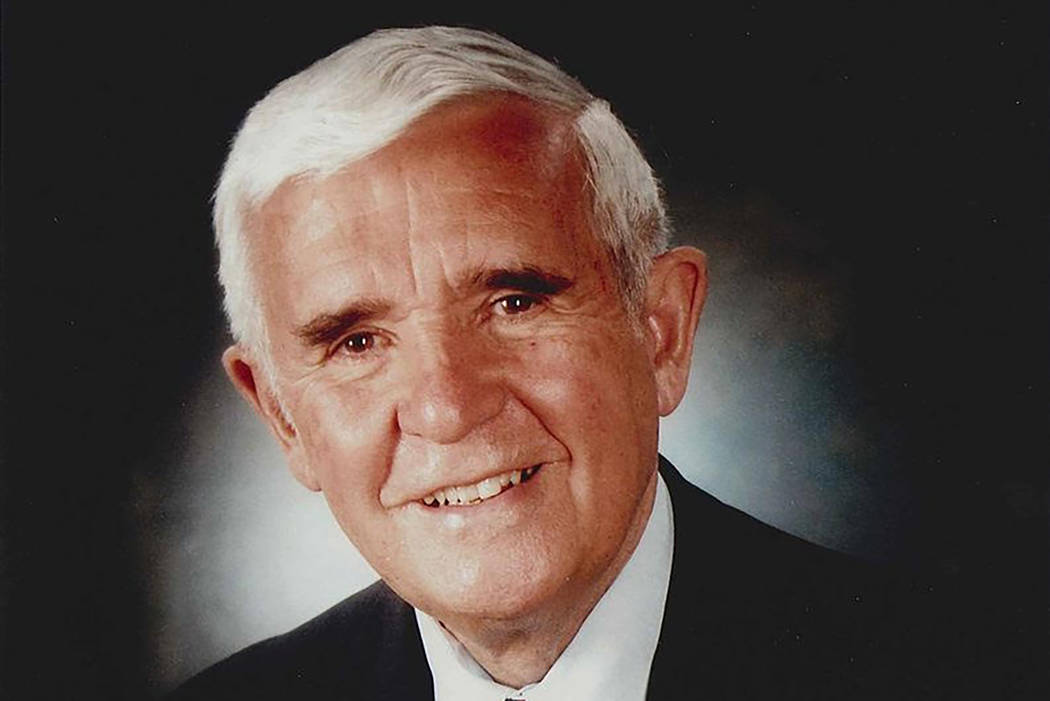

Paul Dominique Laxalt, a sheepherder’s son who became Nevada governor, achieved national prominence as a U.S. senator, modernized the state’s gaming industry and helped redefine the Republican Party, died Monday. He was 96.

His death at a health care facility in northern Virginia was announced by the Ferraro Group public relations firm.

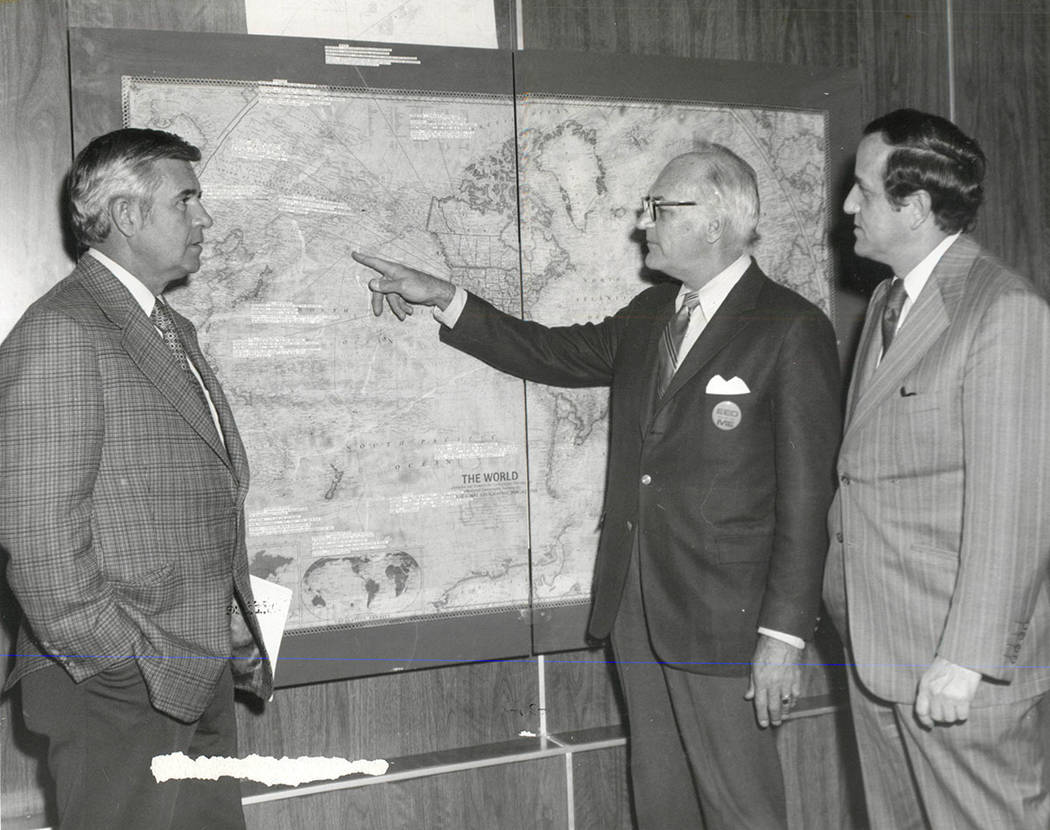

The son of Basque immigrants who settled in Carson City early in the 1900s, Laxalt served as governor from 1967 to 1971, was a U.S. senator from 1974 to 1986 and supported establishment of Nevada’s first community colleges and its first medical school.

Laxalt is survived by his wife, Carol, and five daughters from his first marriage — Gail, Sheila, Michelle, Kevin and Kathleen, and one son, John Paul. Paul Laxalt is the grandfather of current Nevada governor candidate Adam Paul Laxalt.

“My grandfather was the rare man in the arena that never lost sight of who he was or where he came from. It is said that our lives are best remembered not by our achievements but by how we treated others,” Adam Laxalt said in a statement. “In the course of my life, thousands of people have taken the time to tell me that they knew my grandfather. Without exception, they have used words like decent, genuine, honest, humble and kind. He was indeed all of those things. To those closest to me, my grandfather was both a light and a compass: a testament to what a man should be. To me, my grandfather was the ultimate role model, and much of what I know about being an American, a citizen and a leader, I learned from him.”

Here’s a statement from #Nevada Attorney General @AdamLaxalt on the passing of his grandfather, former Nevada governor and U.S. Senator Paul Laxalt. “He was the embodiment of the American dream...” pic.twitter.com/MsUgxxUwRp

— Ramona Giwargis (@RamonaGiwargis) August 7, 2018

Paul Laxalt modernized Nevada’s regulation of gambling and pushed to allow corporations to own casinos, paving the way for gaming as it exists today.

He took the first steps, along with then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan, to regulate development and conservation at Lake Tahoe. Their relationship became a strong one, with Laxalt becoming a confidant of the future president.

Tom Lorentzen, a longtime friend of Laxalt’s who worked on his Senate campaign in 1974, saw Laxalt at his Virginia home on Saturday.

“For the first time, I don’t have any words,” Lorentzen said.

Laxalt was in bed and could not talk. “But we all felt he understood” what they said, Lorentzen said. They were able to talk about how much they loved him.

“He’s legendary in our state,” said a longtime friend and notable Republican campaign strategist Sig Rogich, who worked on Laxalt’s gubernatorial campaign.

News of Laxalt’s death brought an outpouring of support and condolences from Nevada politicians past and present who praised him as a mentor, leader and friend.

“Paul Laxalt was the definition of what a leader should be: Kind, thoughtful and eager to extend a hand in friendship, regardless of political affiliation. His legacy is secured as one of the finest leaders Nevada has ever known,” former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid said in a statement.

“I am devastated by the loss of my friend and mentor, Paul Laxalt today. He was a statesman and a consummate gentleman. May he Rest In Peace,” Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval wrote on Twitter.

I am devastated by the loss of my friend and mentor, Paul Laxalt today. He was a statesman and a consummate gentleman. May he Rest In Peace.

— Governor Sandoval (@GovSandoval) August 7, 2018

“Paul epitomized the very best Nevada to offer by putting service above self. He served as a friend and confidante to numerous Nevadans as his wealth of knowledge steered many of us to seek his valued advice and insight,” U.S. Sen. Dean Heller, R-Nevada, said in a statement.

My full statement on the passing of Paul Laxalt, a mentor, friend, and great public servant: https://t.co/rCMzdPmRXi pic.twitter.com/xtzj3neEfr

— Dean Heller (@SenDeanHeller) August 7, 2018

“Paul Laxalt was a man of determination, honor, and principle. The influence Senator Laxalt had in Nevada and Washington extended across both sides of the aisle, he worked to find common ground,” U.S. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nevada, tweeted.

Paul Laxalt was a man of determination, honor, and principle.The influence Senator Laxalt had in Nevada & Washington extended across both sides of the aisle, he worked to find common ground. Paul and I extend our deepest sympathies to his family.

— Senator Cortez Masto (@SenCortezMasto) August 7, 2018

Early life

Paul Laxalt was born Aug. 2, 1922, in Reno, the oldest of six children.

Laxalt’s middle name was that of his father, Dominique, a sheepherder who immigrated to America in 1906 at the age of 18, among thousands who came from the Basque region of the Pyrenees Mountains of France and Spain.

Dominique built his own herds and became a wealthy stockman before the Great Depression wiped out his fortune. Laxalt’s mother, Therese, was a Basque who came to the United States in 1921 to look after her brother, a French officer who was receiving treatment in California after being gassed in World War I.

They married in 1921. While Dominique rebuilt his herds in the hills and valleys of Western Nevada, Therese did most of the child-rearing in subsequent years.

Therese was able to purchase a small hotel in Carson City. Its few rooms were rented at modest prices to sheepherders and railroad workers. However, Therese had been trained at the Cordon Bleu, France’s premier cooking school, and the hotel restaurant won quick success, serving meals in traditional Basque family style at long tables where the famous and the obscure sat elbow to elbow. Its visitors included Sen. Pat McCarran, D-Nev.

The youngsters spoke Basque before English, according to Laxalt’s brother Robert, who became a noted writer. His 1957 book, “Sweet Promised Land,” told Dominique’s story and became a classic of Western American literature.

After graduating from Carson High School, where he played basketball and rebuffed efforts by his mother and the local monsignor to become a priest, Laxalt attended Santa Clara University in California, a Jesuit school then noted not only for academics but also for sports.

He enlisted in the Army in 1943, where he was a medic dispatched to the Pacific front during World War II. As a member of the 7th Infantry Division, he took part in the invasion of the Gulf of Leyte in the Philippines under Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Returning home, Laxalt took advantage of the GI Bill to put himself through law school at Santa Clara and the University of Denver.

On June 23, 1946, he married Jackalyn Ross, the daughter of John R. “Jack” Ross, a lawyer and a prominent Republican in Northern Nevada. Jack Ross became a professional and political mentor and Jackie became mother to six children, three of whom were adopted as babies.

Life in politics

Before ascending to the Governor’s Mansion, Laxalt was a lawyer who handled defense cases and was an elected district attorney and lieutenant governor.

Dealing with an inmate strike at the Nevada State Prison in 1968, Laxalt as governor agreed to meet with inmates in the prison yard. Asked by reporters afterward about the meeting, he said it had gone fine.

“Hell,” he said. “Many of them were my former clients.”

His tenure as governor was noteworthy also for the unusual relationship he developed with the state’s most famous — and famously reclusive — casino owner, Howard Hughes.

They never met but spoke periodically by telephone as Hughes, from his redoubt on one of the top floors of the Desert Inn in Las Vegas, purchased that resort and a half dozen others with the state’s blessing. Laxalt considered the investments by the shrewd billionaire to be sort of a seal of approval for Las Vegas and its gaming houses that had fallen on hard times.

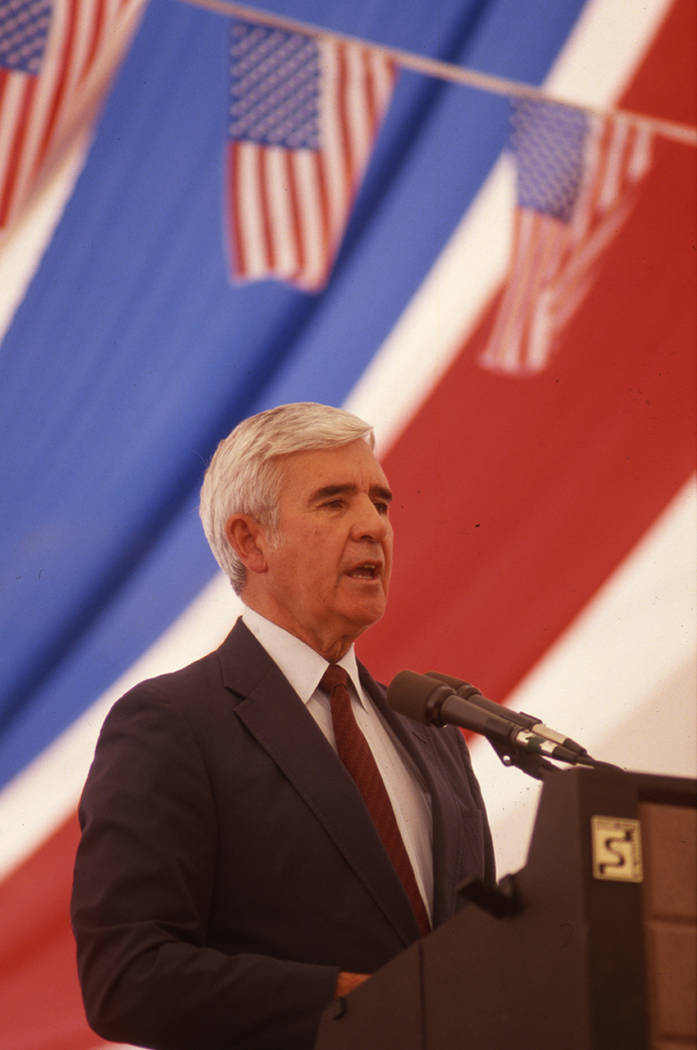

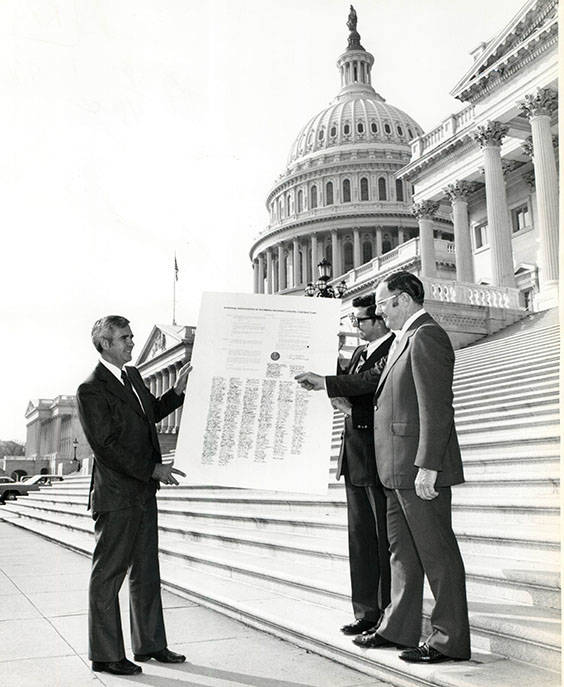

As a Republican senator elected in 1974, Laxalt was a reliable conservative who safeguarded spending for Nevada military bases and fought successfully against a plan to base intercontinental missiles in the deserts of Nevada and Utah.

Laxalt was Lorentzen’s political mentor for 44 years, and for the last 26 years they shared a much more personal relationship.

“I think Paul Laxalt meant as much to Nevada as anybody ever and meant as much to any of us who ever dealt with him as anybody ever,” Lorentzen said.

“He was like my dad.”

Laxalt played a leading role in one of the most contentious foreign policy debates in U.S. history when he fought the treaties that gave control of the Panama Canal to Panama. After nine weeks of Senate debate, Laxalt on April 18, 1978, lost that fight by two votes.

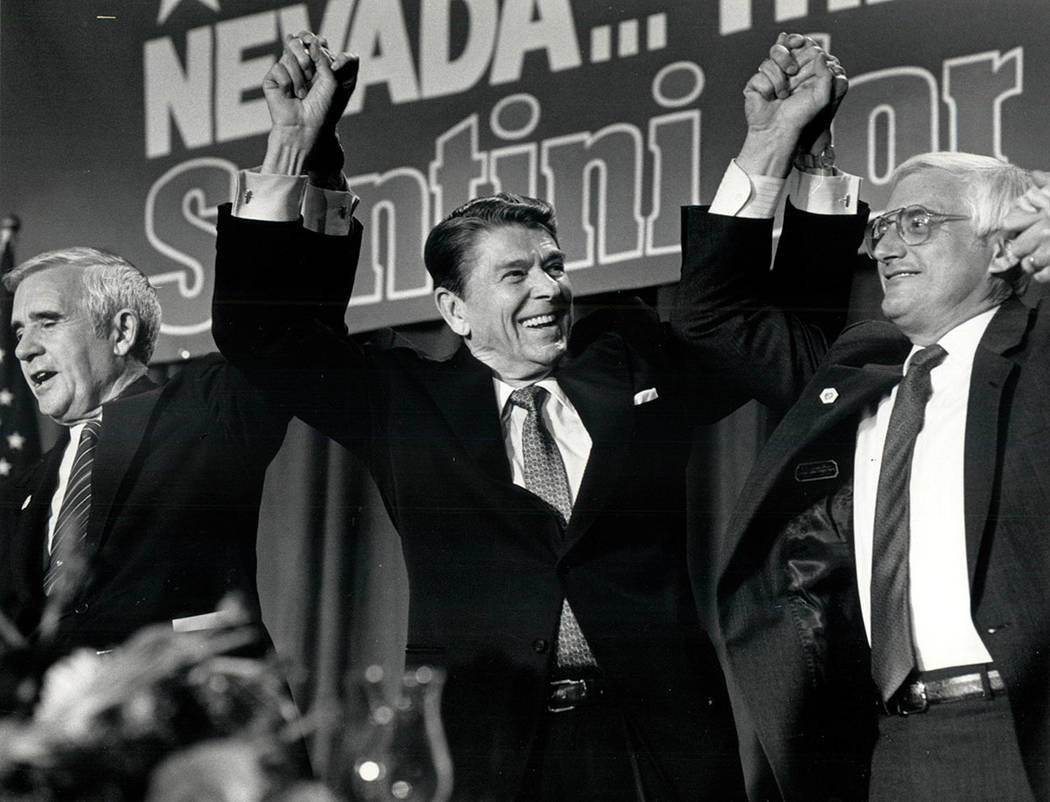

Laxalt’s influence grew immensely as he helped guide Reagan through two terms in the White House.

The two became extremely close through their shared political battles, which included Reagan’s failed challenge to President Gerald Ford for the 1976 Republican nomination, and his election to the White House in 1980 and re-election in 1984.

Laxalt also had the trust of Nancy Reagan, a privilege the first lady did not bestow lightly. He became known in the press as the “First Friend” and was a back channel to the president even for international figures.

It was Laxalt who in 1986 counseled embattled Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos that it was time to “cut and cut cleanly” after the U.S. ally had lost the support of his people and as his country teetered on civil war.

Laxalt met privately several times with Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet Union’s ambassador to the U.S., as the Soviets struggled to understand Reagan.

Another time, as Laxalt was preparing a trip to France, Reagan asked him to take a measure of President Francois Mitterrand.

“What do you think of the guy?” Reagan asked when Laxalt returned from meeting Mitterrand at the French president’s summer home.

“On one wall he had a dozen cowboy hats,” Laxalt told his fellow Westerner. “He can’t be all bad.”

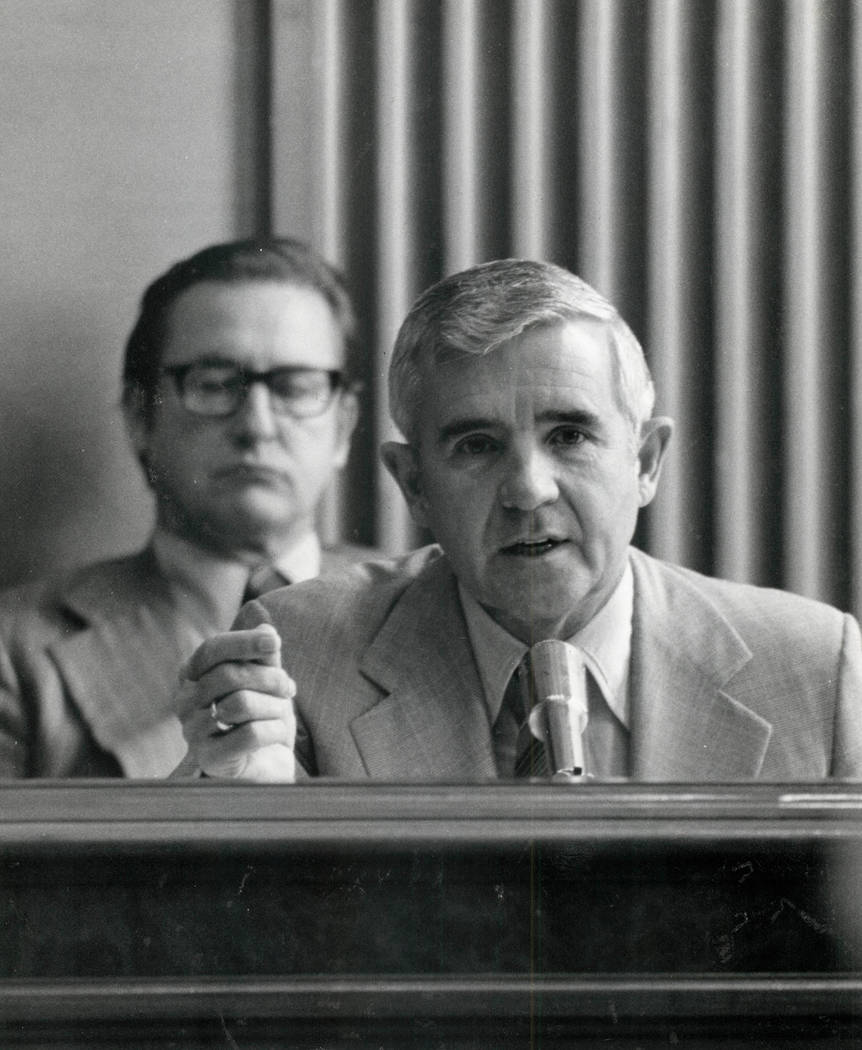

Laxalt enjoyed a reputation as a “straight shooter” among politicians of both parties. In his 2000 memoir, “Nevada’s Paul Laxalt,” he wrote that he could never bring himself to lie to a colleague.

“It made life less complicated,” he added in the memoir.

“One thing about Paul Laxalt: there wasn’t any room for B.S.” Rogich said, adding that the amazing part about Laxalt was the way he cut through the bull.

“He never did it in a harsh way. I never really ever saw him lose it, even when he was maddest,” said Rogich, who like Lorentzen thinks of Laxalt as a father figure and mentor. “I never saw him scream at someone, throw a tantrum. He was gentle at all times. Sincere.”

The Senate Laxalt inhabited was much different than the partisan-wracked body today. Then, senators forged relationships across party lines.

“In the early days of my Senate career, politics reared its head at election time, but rarely carried over,” Laxalt wrote in his memoir. “The Senate was a ‘comfort zone’ for all its members.”

Laxalt helped to install by his count at least 10 Nevadans into federal posts during the Reagan years, a record perhaps topped only by his Senate successor, Democrat Harry Reid, who later became Senate majority leader.

“We came from different political parties and backgrounds, but that didn’t matter to Paul Laxalt,” Reid said. “He was the epitome of a gentleman. He treated me, and everyone, with the utmost respect and friendship. I saw him exhibit these qualities first-hand, working alongside him as he served as Nevada’s Lieutenant Governor, Governor and U.S. Senator.”

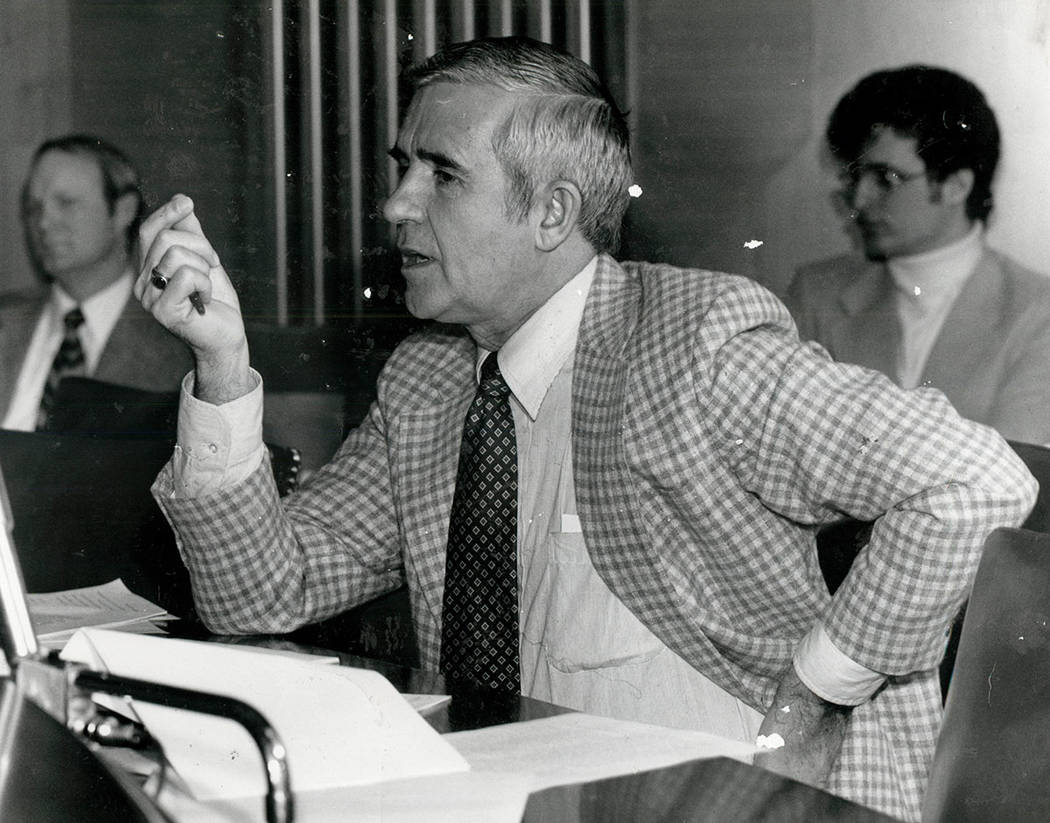

Prodded by conservatives who saw him as Reagan’s true heir, Laxalt in 1987 launched what he later acknowledged was an ill-considered run for the presidency. Laxalt abandoned the effort when it became clear he would have trouble raising money and as many Reaganites — and Reagan himself — appeared committed to Vice President George H.W. Bush in the 1988 race.

Laxalt called his bid for president “the four most miserable months of my life,” and he set off to make a new path for himself.

The Nevadan did not court attention after he ended his public career. He established a consulting business, was sought out as a senior Republican wise man and retired to the home he and his wife Carol had built in the Washington suburb of McLean, Virginia.

Into politics

In his first attempt at office Laxalt won election in 1950 to become part-time district attorney of Ormsby County, which at the time contained Carson City, the smallest state capital that still had dirt streets petering out in pasturelands. The county was dissolved in 1969, with Carson City taking over governance and services.

Laxalt was elected lieutenant governor in 1962 and served under Democrat Grant Sawyer, who made enemies including FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who Sawyer had criticized for meddling in Nevada’s legal gambling industry.

In 1964, Laxalt challenged Democratic incumbent Sen. Howard Cannon. The race was neck and neck even though GOP presidential candidate Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona was in the process of being beaten soundly by President Lyndon Johnson. Laxalt, who spent Election Day in Carson City, was told that night he had won. But after flying to Las Vegas the next morning, he was stunned upon being told the returns from late-reporting Southern Nevada precincts had resulted in a 48-vote victory for the Las Vegas-based Cannon.

Amidst cries of fraud from Republicans and following a recount, Laxalt trailed by 84 votes and decided not to contest the race further.

“We suspected the worst but weren’t able to prove it clearly,” Laxalt wrote later. “One consolation was the fact at least I didn’t have to move my family to that dreaded Washington.”

Laxalt was back two years later in a run for governor, and he defeated Sawyer by 5,900 votes.

Although later considered quite conservative, Laxalt backed several progressive programs while governor.

Though ideologically opposed to President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” programs, such as the National Endowment for the Arts, Laxalt helped create the Nevada State Council on the Arts to obtain funding from the NEA.

Laxalt talked fellow Republicans into raising taxes to finance schools at the same rate they had been under Sawyer — then one of the most generous education funding levels in the nation.

In the early Laxalt years, Nevada was the only state without a community college. He overcame resistance from boosters of Reno’s University of Nevada campus to fund community colleges started by local leaders in Elko and Southern Nevada. He was especially proud of advocating and organizing support for Nevada’s first medical school.

After serving a four-year term as governor, Laxalt in 1971 suffered from burnout.

“I just had a gut full of politics,” he told the Review-Journal in a 2000 interview. “Had a gut full of the limelight, and I just wanted to go home and did.”

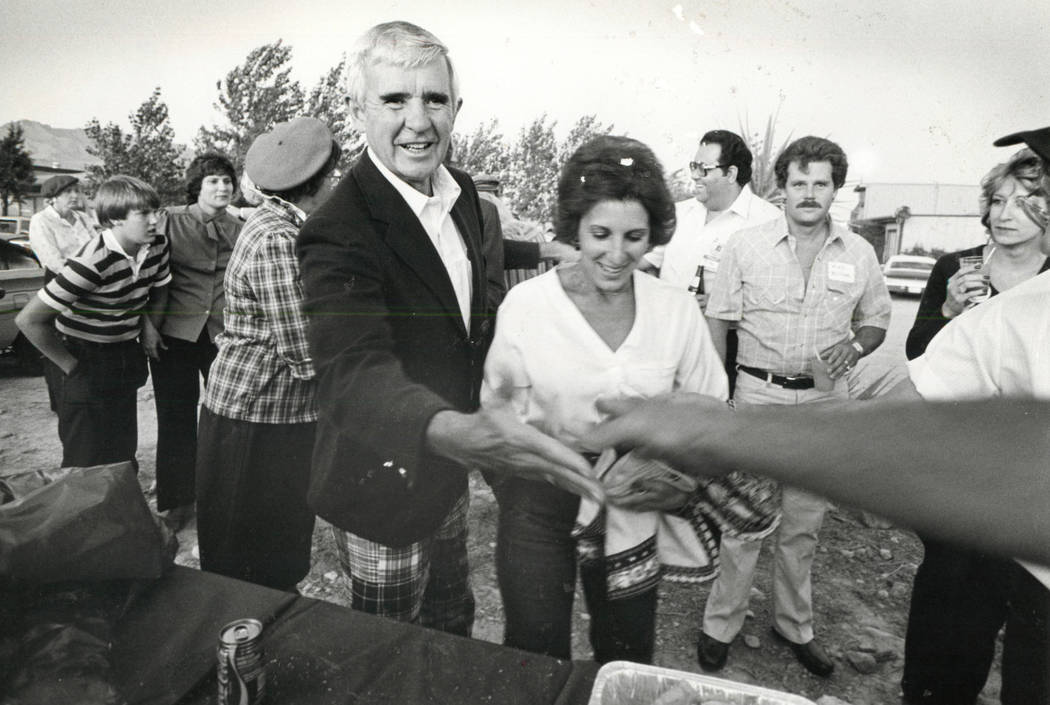

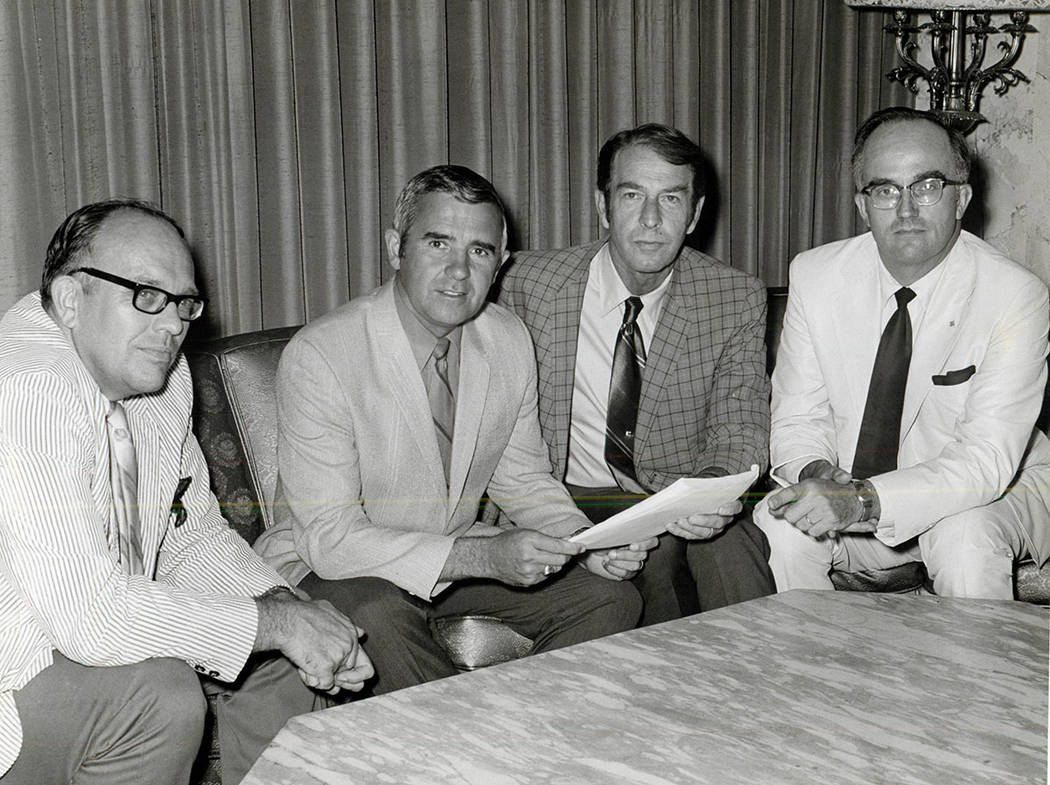

In 1974, when Sen. Alan Bible announced his retirement, Republicans pressed Laxalt back into public life, and he ran for Senate against lieutenant governor Reid and won by 624 votes. Reid later admitted he managed to find a way to lose in an otherwise post-Watergate banner year for Democrats.

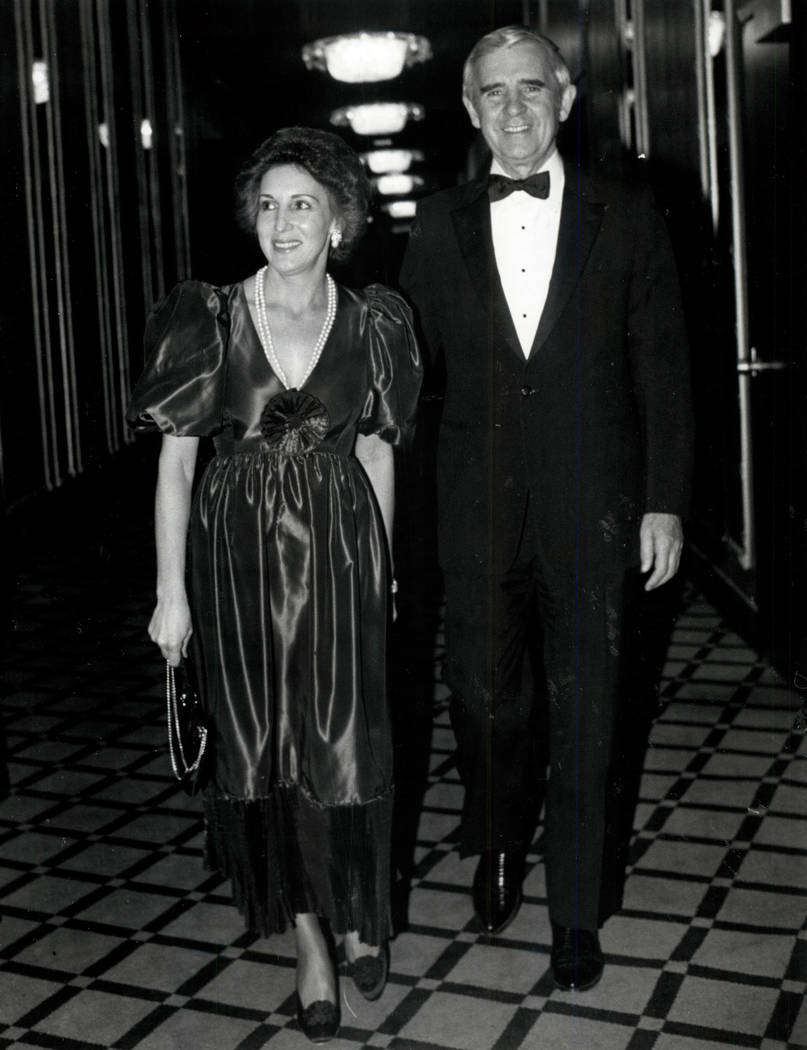

In 1972 Laxalt’s first marriage ended in divorce, and on Dec. 31, 1975, he married Carol Wilson, his office manager while he was governor and during his initial years in the Senate.

Laxalt entered the hotel-casino business, fulfilling a family ambition of building a new Ormsby House in Carson City, after the original was bought by his father in the early 1900s and later demolished.

Laxalt sued the Sacramento Bee for libel in 1984 after the California newspaper claimed that federal agents alleged the casino had been skimmed of profits under Laxalt family ownership. Laxalt sought $250 million in damages. The suit was settled in 1987 and in 1988 Laxalt was awarded $647,452.

Laxalt served an eventful two terms and retired from Capitol Hill in 1986.

Reagan connections

Laxalt and former Hollywood star Reagan crossed paths in 1964 through their shared association with GOP presidential candidate Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona — Laxalt as a Republican officeholder in neighboring Nevada and Reagan as a campaigner for the presidential hopeful.

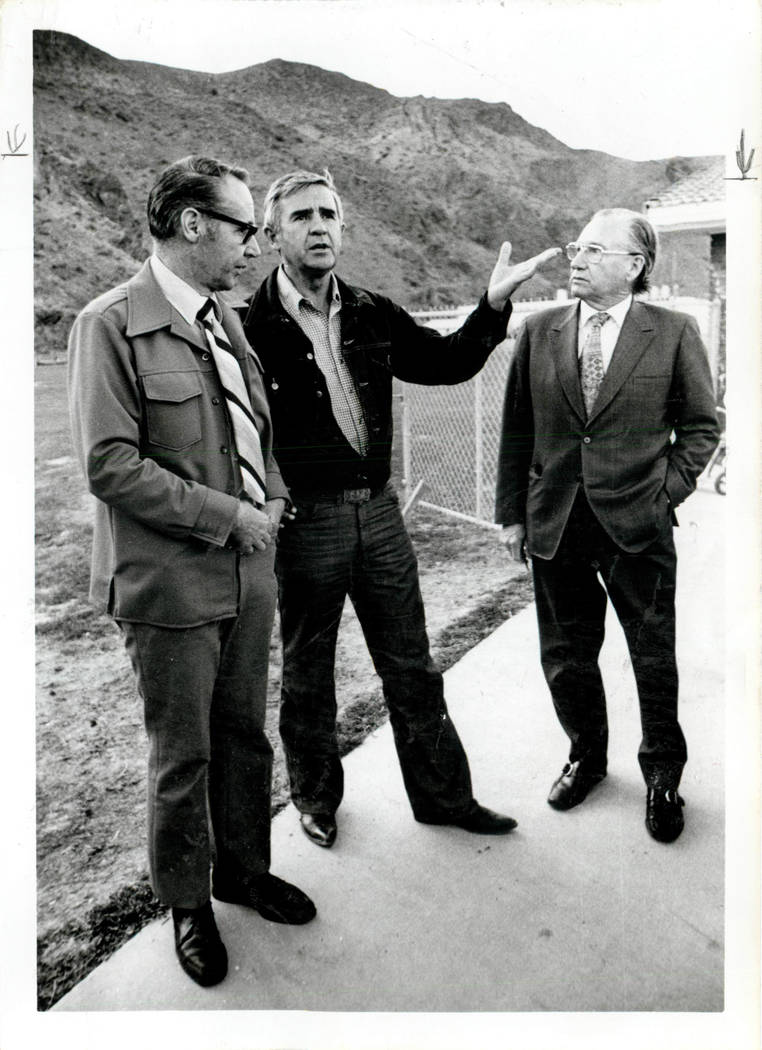

Years later, as governors of adjoining states Laxalt and Reagan conferred on fiscal matters, and most notably over strategy to preserve the bi-state borders of Lake Tahoe that were being threatened with over-development.

“It was apparent that unless we did something Tahoe stood a real chance of turning gray on our watch,” Laxalt told University of Virginia researchers in a 2001 oral history of his relationship with Reagan.

Legislatures in both states eventually acted, and in 1969 Congress ratified an agreement creating the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

At governors conferences, Laxalt would shepherd Reagan, who was not as familiar with or comfortable around the political scene. A friendship grew.

Laxalt, a junior senator, headed Reagan’s 1976 campaign against Ford, an incumbent from the same party. At the Republican convention in Kansas City, Missouri, Ford defeated Reagan in a convention hall drama, but Laxalt said Ford “never held it against me.”

Laxalt headed Reagan’s winning presidential bids in 1980 and 1984, and served as the president’s unofficial liaison to the Senate during the remainder of his term.

The Nevadan was nearby during the highlights and lowlights of Reagan’s terms, including the passage of his economic programs, the 1981 attempt on his life and the Iran-Contra scandal where the president was stunned to learn officials in his administration had secretly sold arms to Iran and used the proceeds to fund U.S,-backed rebels in Nicaragua.

Laxalt’s standing in the president’s inner circle was acknowledged on Capitol Hill when Majority Leader Howard Baker designated him a non-elected member of the Senate leadership, a post without precedent.

After Republicans lost 27 House seats in the 1982 elections, Reagan moved to shore up the party and asked Laxalt to head the Republican National Committee. Laxalt declined, saying it would require him to resign as senator.

Attorneys found another way, and Laxalt agreed to become “general chairman” of the party, an overseer role. He installed fellow Nevadan Frank Fahrenkopf to run the national committee on a day to day basis.

After two Senate terms, Laxalt decided to exit, but he and Carol stayed in northern Virginia, where he worked as a lawyer.

Funeral services are pending.

Colton Lochhead, Debra J. Saunders and A.D. Hopkins contributed to this story.

Paul Laxalt Timeline

Aug. 2, 1922: Paul Dominique Laxalt is born in Reno.

1946: Laxalt marries Jackalyn Ross, daughter of John R. "Jack" Ross, a prominent lawyer and Republican in Northern Nevada.

1944: An Army medic, Laxalt is sent to the Battle of Leyte in the Philippines during World War II.

1951-55: Laxalt serves as district attorney of what was then Ormsby County, where Carson City was located. It was his public office.

1963-67: Laxalt serves one term as lieutenant governor of Nevada.

1964: While lieutenant governor, Laxalt unsuccessfully runs for the U.S. Senate, losing by 48 votes to Democratic incumbent Howard Cannon.

1967-71: Laxalt serves one term as governor in Nevada, defeating incumbent Gov. Grant Sawyer. After his term, Laxalt and family open a casino, the Ormsby House, in Carson City.

1974-86: Laxalt serves in the U.S. Senate. Gov. Mike O'Callaghan appointed Laxalt to finish the term of U.S. Sen. Alan Bible, who announced his retirement after Laxalt won the 1974 election.

Dec. 31, 1975: Laxalt marries his second wife, Carol.

1980: Laxalt wins re-election to the U.S. Senate, while serving as co-chairman of Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign. Laxalt was national chairman of Reagan's presidential campaigns in 1976, 1980 and 1984.

Aug. 6, 2018: Laxalt dies at a health care facility in northern Virginia.